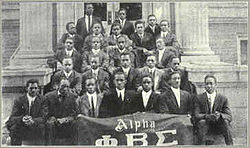

| Phi Beta Sigma | |

|---|---|

| ΦΒΣ | |

|

|

| Founded | January 9, 1914 Howard University |

| Type | Social |

| Emphasis | Service |

| Scope | International Germany Bahamas South Korea Japan Switzerland Africa & Worldwide |

| Motto | Culture For Service and Service For Humanity |

| Colors | Royal Blue Pure White |

| Symbol | Dove |

| Flower | White Carnation |

| Publication | The Crescent |

| Chapters | 700+ |

| Members | 290,000+ lifetime |

| Nickname | Phi Betas Sigmas |

| Headquarters | 145 Kennedy Street, NW Washington, D.C. United States |

| Homepage | www.phibetasigma1914.org |

|

|

Phi Beta Sigma (ΦΒΣ) is a social/service collegiate and professional fraternity founded at Howard University in Washington, D.C. on January 9, 1914, by three young African-American male students with nine other Howard students as charter members. The fraternity’s founders, A. Langston Taylor, Leonard F. Morse, and Charles I. Brown, wanted to organize a Greek letter fraternity that would exemplify the ideals of Brotherhood, Scholarship and Service while taking an inclusive perspective to serving the community as opposed to having an exclusive purpose. The fraternity exceeded the prevailing models of Black Greek-Letter fraternal organizations by being the first to establish alumni chapters, to establish youth mentoring clubs, to establish a federal credit union, to establish chapters in Africa, and establish a collegiate chapter outside of the United States, and is the only fraternity to hold a constitutional bond with a predominantly African-American sorority, Zeta Phi Beta (ΖΦΒ), which was founded on January 16, 1920, at Howard University in Washington, D.C., through the efforts of members of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity.

The fraternity expanded over a remarkably broad geographical area in a short amount of time when its second, third, and fourth chapters were chartered at Wiley College in Texas and Morgan State College in Maryland in 1916, and Kansas State University in 1917. Today, the fraternity serves through a membership of more than 200,000 men in over 700 chapters in the United States, Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Caribbean. Although Phi Beta Sigma is considered a predominantly African-American Fraternity, its membership also consists of diverse college-educated men of African, Caucasian, Hispanic, Native American and Asian descent. According to its Constitution, academically-eligible male students of any race, religion, or national origin may join while enrolled at a college or university through collegiate chapters, or professional men may join through an alumni chapter if a college degree has been attained, along with a certain minimum number of earned credit hours.

Phi Beta Sigma is a member of the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC) and the North-American_Interfraternity_Conference (IFC or NIC). The current International President is Jonathan A. Mason, and the fraternity’s headquarters are located at 145 Kennedy Street, NW Washington, D.C.

- 1History

- 2Purpose of the fraternity

- 3Membership

- 4The national programs

- 5See also

- 6Further reading

- 7References

- 8External links

History[edit]

Genesis and founding (1910–1916)[edit]

In the summer of 1910, after a conversation with a recent Howard University graduate in Memphis, Tennessee, A. Langston Taylor formed the idea to establish a fraternity and soon after, enrolled into Howard University in Washington, D.C. Once there, Taylor began to set his vision of a brotherhood into action. In October 1913, Taylor and Leonard F. Morse had their initial conversation about starting a fraternity. As a result, Charles I. Brown was named as the third member of the founding group. By November 1913, a committee was established to begin to lay the foundation of what was to become Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity. Soon after the first committee meeting, Taylor, Morse, and Brown chose 9 associates to assist them with the creation of the fraternity. Those men were the first charter members of the organization.

On January 9, 1914, the permanent organization of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity was established in the Bowen Room of the 12th Street Y.M.C.A Building in Washington, D.C. On April 15, 1914, the Board of Deans at Howard University officially recognized Phi Beta Sigma and the following week The University Reporter, Howard University’s student publication, made known the news.

The first two years of the fraternity’s existence would see them organize and maintain a Sunday school program, led by A.H. Brown, open a library and art gallery to the public, the foundation of the Benjamin Banneker Research Society, and also the Washington Art Club.[1] In addition to their impact to the Washington, D.C. Community, the members of Sigma were also impacting the campus of Howard University. Abraham M. Walker was elected associate editor of the Howard University Journal. The following year, Walker and Founder A. Langston Taylor, were elected Editor-in-Chief and circulation manager respectively. Other members were also taking leadership positions as W.F. Vincent, William H. Foster, John Berry, Earl Lawson, among others, were presidents of the Debating Society, the college YMCA, the Political Science Club, and the Athletic Association respectively. On the athletic field, captain John Camper and J. House Franklin were standout football players for Howard University.

In the spring of 1915, the fraternity was seeking to further its intellectual pool. As a result, several affluent African-American scholars Dr. Edward P. Davis, Dr. Thomas W. Turner, T.M. Gregory, and Dr. Alain Leroy Locke, were inducted into the Fraternity. On March 5, 1915, Herbert L. Stevens was initiated, in turn making him the first Graduate member of Phi Beta Sigma.[2]

A year after the establishment of Phi Beta Sigma, the Fraternity saw that the scope of Sigma needed to be expanded beyond just Washington, D.C. and Howard University. On November 13, 1915, Beta Chapter was chartered at Wiley College in Marshall, Texas by graduate member Herbert Stevens. Beta chapter became the first chapter of any African-American Greek-lettered organization to be chartered south of Richmond, Virginia.[2] As Phi Beta Sigma continued its expansion in the Eastern and Southern United States, other national fraternities were beginning to take notice.

On December 28, 1916, Phi Beta Sigma hosted the fraternity’s first conclave in Washington, D.C. 200 members representing three collegiate chapters, Alpha, Beta and Gamma (established at Morgan State College) were in attendance. As a result of the 1916 conclave, an official publication for the Fraternity was authorized and member W.F. Vincent was elected as the National Editor.

World War I and the Sigma call to arms (1917–1919)[edit]

Phi Beta Sigma responded to a “Call to Arms” in 1917 as the United States entered the First World War. No definite study has ever been made as to the participation of Sigma brothers in World War I. However, the extent of their activity may be suggested by the fact that the Alpha chapter had about seventy members in uniform.[3] The troubles of membership, not only affected the Alpha Chapter. Other chapters of Sigma were so depleted that only the Alpha Chapter showed any signs of activity and the National Office ceased to function. The General Board was forced to re-organize as a result of death and other dislocations brought on by the war. Fraternity President I. L. Scruggs would ask Founder, and now the fraternity’s National Treasurer, A. Langston Taylor to contact the Brothers as soon as they re-appeared in civilian clothes.[4] It was through the efforts of Taylor that the fraternity was able to continue and proceed to operate financially as numerous Sigma men served on the European battle front.[4]

Incorporation and the founding of Zeta Phi Beta (1920–1933)[edit]

By February 1920, Phi Beta Sigma had expanded to Ten active chapters; including the Eta Chapter at The Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina (now North Carolina A&T State University).[5] As a result of the December 1919 Conclave, Phi Beta Sigma’s first conclave after the war, fraternity founder A Langston Taylor was given approval from the General Board to assist in the organization of what was to become the sister sorority to Phi Beta Sigma.

The creation of Zeta Phi Beta Sorority[edit]

In the spring of 1919, Sigma Brother, Charles Robert Samuel Taylor shared with Arizona Cleaver his idea for a sister organization to the fraternity. Cleaver then presented this idea to fourteen other Howard Women; and with the help of Charles Taylor and Sigma Founder A. Langston Taylor, work began to establish the new sorority.[6] With permission from the Howard University administration, Zeta Phi Beta Sorority held its first official meeting on January 16, 1920. The founders and charter members of the Sorority consisted of Arizona Cleaver (Stemons), Viola Tyler (Goings), Myrtle Tyler (Faithful), Pearl Anna Neal, and Fannie Pettie (Watts). The five founders chose the name Zeta Phi Beta. The similar names of both Sigma and Zeta are intentional in nature as the ladies adopted the Greek letters ‘Phi’ and ‘Beta’ to “seal and signify the relationship between the two organizations”.[7]

“Arizona Cleaver was the chief builder and she asked fourteen others to join her. I shall never forget the first meetings held in dormitory rooms of Miner Hall. Miss Hardwick, the matron, never knew I was about until I was escorted out by Arizona, who was her assistant. I was Miss Hardwick’s favorite boy.”

Sigma Brother Charles R. Taylor

(On Arizona Cleaver & the organization of Zeta Phi Beta)[8]

The newly established Zeta Phi Beta Sorority was given a formal introduction at the Whitelaw Hotel by their Sigma Counterparts, Charles R. and A. Langston Taylor. The two Sigma Brothers had been a source of advice and encouragement during the establishment, and throughout the early days. of Zeta Phi Beta[9] As National Executive Secretary of Phi Beta Sigma, Charles Taylor wrote to all Sigma Chapters requesting they establish Zeta chapters at their respective institutions. With the efforts of Taylor, Zeta added several chapters in areas as far west as Kansas City State College; as far south as Morris Brown College in Atlanta, Georgia; and as far north as New York City.[10]

Phi Beta Sigma’s contributions to the Harlem Renaissance[edit]

The 1920s also witnessed the birth of the Harlem Renaissance- a flowering of African-American cultural and intellectual life which began to be absorbed into mainstream American culture. Phi Beta Sigma fraternity brother Alain LeRoy Locke is unofficially credited as the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance.” His philosophy served as a strong motivating force in keeping the energy and passion of the Movement at the forefront.[11] In addition to Locke, Sigma brothers James Weldon Johnson and A. Philip Randolph were participants in this creative emergence led primarily by the African-American community based in the neighborhood of Harlem in New York City.

On January 31, 1920, Phi Beta Sigma was incorporated in the district of Washington, D.C. and became known as Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Incorporated.

In November 1921, the first volume of the Phi Beta Sigma Journal was published. The journal was the official organ of the fraternity and Eugene T. Alexander was named its first editor. The following month, the fraternity held its 1921 Conclave at Morris Brown College in Atlanta, Georgia. This conference saw the first ever inter-fraternity conference between Phi Beta Sigma and Omega Psi Phi. This would lead to the first inter-fraternity council meeting between the two organizations the following spring in Washington, D.C.

“When Taylor left the center of the stage, the main theme of the plot had been introduced. It would, of course, be developed, embellished, and varied in the years to come.”

Brother I.L. Scruggs[12]

In 1922, Founder Taylor called for the assembly of the Black Greek Lettered Organizations of Howard University to discuss the formation of a governing council. Although, the efforts of Taylor failed on that particular day, they would sow the seeds for what was to become the National Pan-Hellenic Council eight years later.

In March 1924, the name of the fraternity’s official publication, The Phi Beta Sigma Journal, was changed to The Crescent Magazine. The magazine’s name change was suggested by members of the Mu Chapter at Lincoln University, PA to reference the symbolic meaning of the crescent to the fraternity. At the 1924 conclave, the concept of the Bigger and Better Negro Business was introduced by way of an exhibit devoted to the topic. This would lead to the establishment of Bigger and Better Business as a national program at the 1925 conclave. At the 1928 Conclave, held in Louisville, Kentucky, the tradition of branding the skin with a hot iron, as a part of the initiation process was officially frowned upon.

Sigma and the Great Depression[edit]

At the 1929 Conclave held in New York City, Dr. Carter G. Woodson was invited as a guest speaker and saw the creation of The Distinguished Service Chapter. The fall of 1929 saw the crash of the nation’s stock markets. Like many others during this period, Phi Beta Sigma also suffered a common fate. With brothers faced with financial worries, some members were forced to leave their respective institutions and chapters became inactive. The Fraternity saw its income drastically shrink to the point of nearly disappearing completely. As a result of the bank closures, the remaining funds of the Fraternity were frozen.

“Negroes would warrant and get Support and Patronage from other races as well as the Negro race”

Arthur W. Mitchell[12]

6th International President of ΦΒΣ

As the nation came to terms with the Great Depression, Phi Beta Sigma and its members continued to implement programs to support the black community. In February 1930, the General Board met in New York City and appointed then vice president of the Eastern Region Dr. T. H. Wright as head of the new Bigger and Better Business program. The first objective of Phi Beta Sigma’s new program was to call upon colleges to provide business courses for its students. The fraternity went forward with its plans to implement the bigger and better business program and aid as many financially strapped chapters as possible through scholarships for brothers.

Later that year, at the 1930 Conclave held in Tuskegee, Alabama, northern region vice president C.L. Roberts suggested that instead of a yearly meeting, the annual conclaves should be held once every two years. It was also at this conclave that brother George Washington Carver delivered an impassioned and emotional speech to the brothers in attendance.

Social action and international expansion (1934–1949)[edit]

Fraternity brother A. Phillip Randolph, who organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, played a role in the amendments to the Railway Labor Act in 1934. As a result, railway porters were granted rights under federal law. This victory and the continuing work of Randolph and the BSCP led to the Pullman Company contract with the union, which included over $2 million in pay increases for employees, a shorter workweek, and overtime pay. 1934 also marked the birth of Social Action as a national program and the return of founder A. Langston Taylor to the forefront of Sigma. Brother Emmett May was elected as the first director of the social action initiative.

The 1935 Atlanta Conclave saw yet another meeting between Sigma and Omega Psi Phi fraternities. Omega founders Edgar Amos Love and Oscar James Cooper brought greetings to the brothers in attendance of the conference on behalf of the members of Omega Psi Phi. The following year, the general board approved the fraternity’s affiliation with the already established National Pan-Hellenic Council. in continuation of Sigma’s Social Action initiative, brothers of Sigma were actively involved the Chicago meeting of the National Negro Congress.

We live in daily hope that we shall one day learn the fate of our beloved brother and founder.

Founder Leonard F. Morse – 1949

(On The fate of Founder Charles I. Brown)[13]

As Phi Beta Sigma prepared for the Silver (25th) Anniversary, a special search was made for lost founder Charles I. Brown. The search would yield no results as to the fate or location of Founder Brown. The 1939 conclave marking the 25th anniversary of the fraternity was held on the campus of Howard University.

At the 1941 Conclave in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the fraternity became a permanent member of the National Negro Business League. At the same conclave Brother A. Phillip Randolph announced a proposed march on Washington, D.C., to protest racial discrimination in defense work and the armed forces. This proposed march would lead then president of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt to create the Committee on Fair Employment Practice and issue Executive Order 8802 which barred discrimination in governmental and defense industry hiring.

Due to the outbreak of the Second World War no Conclaves were held, although some brothers in various regions were able to assemble independently of the General Board. At the fraternity’s first spring conclave in 1944, the fraternity voted to support the United Negro College Fund. 1949 would mark the reunion of two of the founders of Sigma: A. Langston Taylor and Leonard F. Morse.

The 1940s and 1950s would show the continued expansion of Phi Beta Sigma. In 1949, the fraternity became an international organization with the chartering of the Beta Upsilon Sigma graduate chapter and the Gamma Nu Sigma graduate chapter in Monrovia, Liberia. The fraternity would extend its international chapters into Geneva, Switzerland, with the chartering of the Gamma Nu Sigma graduate chapter in 1955.

Sigma and the Civil Rights Movement (1950–1969)[edit]

As the struggle for the civil rights of African Americans renewed in the 1950s, Sigma men held positions of leadership among various civil rights groups, organized protests, and proposed the famous March on Washington of 1963. In Atlanta, A. Phillip Randolph helped with the establishment of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957. Randolph and fraternity brother John Lewis would later be involved with the 1963 March on Washington, Randolph as a key organizer and Lewis as a speaker representing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

In 1961, Phi Beta Sigma brother James Forman joined and became the executive secretary of the then newly formed Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. From 1961 to 1965 Forman, a decade older and more experienced than most of the other members of SNCC, became responsible for providing organizational support to the young, loosely affiliated activists by paying bills, radically expanding the institutional staff, and planning the logistics for programs. Under the leadership of Forman and others, SNCC became an important political player at the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

During the Selma to Montgomery marches, Brothers Hosea Williams and John Lewis (U.S. politician) led a 54-mile protest march from Selma to the capital of Alabama: Montgomery. Lewis became known nationally for his prominent role in the marches and became a Congressman as a Democrat from Georgia. During police attacks on the peaceful demonstration Lewis was beaten mercilessly, leaving head wounds that are still visible today.

Phi Beta Sigma brother Huey P. Newton helped establish the revolutionary left-wing Black Panther Party. Originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, their goal was the protection of African-American neighborhoods from police brutality in the interest of African-American justice. As one of the many advocates of The Black Power Movement, the Black Panthers were considered part of one of the most significant social, political, and cultural movements in U.S. history. “The Movement[‘s] provocative rhetoric, militant posture, and cultural and political flourishes permanently altered the contours of American Identity.”[14]

History (1970–2000)[edit]

In 1970, brother Melvin Evans was elected the first governor of the United States Virgin Islands. In 1979, Phi Beta Sigma celebrated its 65th anniversary Conclave in Washington, D.C. In 1983, Sigma brother Harold Washington became the first African-American mayor of the city of Chicago, Illinois. In 1986, the Fraternity opened the Phi Beta Sigma Federal Credit Union which is open to members of the Fraternity, members of the sister sorority, Zeta Phi Beta, their families, and their respective Regions and Chapters. With the establishment of the credit union, Phi Beta Sigma became the first NPHC organization to offer such an entity to its members.[citation needed]

In 1989, the Fraternity celebrated its Diamond Jubilee in Washington, D.C. Also in that year, brother Edison O. Jackson became the president of Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn, New York. In 1990, two Sigma brothers made significant firsts in their respective fields as Brothers Charles E. Freeman and Morris Overstreet were elected the first district judge of the Illinois Supreme Court and first African-American elected by popular vote to a statewide office in the state of Texas respectively. In 1995, the fraternity was the only NPHC organization involved with the planning and support of the Million Man March as brother Benjamin Chavis Muhammad served as national coordinator of the March.[citation needed]

21st century[edit]

In 2001, Sigma brother Rod Paige became the first African American Secretary of Education. At the 2003 conclave, in Memphis, Tennessee, the fraternity added Projects S.W.W.A.C & S.A.T.A.P as national programs in attempts to combat cancer and teenage pregnancy.[15] In addition to those projects, the fraternity added Project Vote and the Phi Beta Sigma Capital Hill Summit under the social action umbrella.[15]At the 2007 conclave in Charlotte, North Carolina the fraternity introduced the Sigma Wellness initiatives as the latest national programs. The 2009 Conclave in New Orleans saw former President William Jefferson Clinton accept honorary member invitation to Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity.”[16]

Purpose of the fraternity[edit]

The founders deeply wished to create an organization that viewed itself as “a part of” the general community rather than “apart from” the general community. They believed that each potential member should be judged by his own merits rather than his family background or affluence… without regard of race, nationality, skin tone or texture of hair. They wished and wanted their fraternity to exist as part of even a greater brotherhood which would be devoted to the “inclusive we” rather than the “exclusive we.” The fraternity’s defiance of stereotypes that have plagued other organizations indeed goes back to the founders themselves with their careful and deliberate building of the fraternity by promoting a membership with diverse backgrounds.

From its inception, the Founders also conceived Phi Beta Sigma as a mechanism to deliver services to the general community. Rather than gaining skills to be utilized exclusively for themselves and their immediate families, the founders of Phi Beta Sigma held a deep conviction that they should return their newly acquired skills to the communities from which they had come. This deep conviction was mirrored in the Fraternity’s motto, “Culture For Service and Service For Humanity.”

Today, Phi Beta Sigma has blossomed into an international organization of leaders. The fraternity has experienced unprecedented growth and continues to be a leader among issues of social justice as well as proponent of the interests of minority communities, the needy, the oppressed, and the youth. No longer a single entity, the Fraternity has now established the Phi Beta Sigma Educational Foundation, the Phi Beta Sigma Housing Foundation, the Phi Beta Sigma Federal Credit Union, a notable youth auxiliary program, “The Sigma Beta Club,” and the Phi Beta Sigma Charitable Outreach Foundation.

Membership[edit]

Phi Beta Sigma’s Constitution states that race, religion, and national origin are not criteria for membership. Membership is predominantly African-American in composition, with members in over 650 collegiate and alumni chapters in the United States, District of Columbia, Germany, Switzerland, The Bahamas, Virgin Islands, South Korea, Japan and countries in Africa. Since its founding in 1914, more than 150,000 men have joined the membership of Phi Beta Sigma.[citation needed]

“Each one, was different in temperament, in ability, in appearance; but that was why they were chosen by the three founders. We felt that a fraternity composed of men who were all alike in habits, interest and abilities would be a pretty dull organization.”

Sigma Co-Founder Leonard F. Morse

(On The First Initiated Brothers of Phi Beta Sigma)[17]

A chapter name ending in “Sigma” denotes a graduate chapter. No chapter of Phi Beta Sigma is designated Omega, the last letter of the Greek alphabet, and deceased brothers are referred to as having joined The Omega Chapter.

Pledging and hazing culture[edit]

Through the years, members of Phi Beta Sigma have been involved in incidents related to hazing, although now denounced by the fraternity, incidents have been discovered of pledges being subjected to activities which in some case have resulted in serious injury and even death. Prior to 1990, the Crescent Club was the official pledge club of Phi Beta Sigma and potential candidates interested in becoming a member of the fraternity would join the pledge club before being fully initiated. In response to the increasing number of lawsuits stemming from allegations and incidents related to hazing, Phi Beta Sigma and other members of the National Pan-Hellenic Council jointly agreed to disband pledging as a form of admission.[18] In an attempt to eliminate Hazing from these organizations, each revised its orientation procedures and developed the Membership Intake Process.

In 2012, then Phi Beta Sigma International President Jimmy Hammock, along with the National Action Network, led by Sigma member Al Sharpton, launched a coalition whose aim was to combat hazing culture not just within the black Greek Lettered Organizations, but also the broader community at large. The coalition, also pledged their support of federal anti-hazing legislation that was being spearheaded by former United States House of Representatives member Frederica Wilson.[19][20] As part of the campaign, the fraternity developed anti-hazing training materials, held a town hall meetings, facilitated workshops and encouraged local chapters to participate in the annual National Anti-Hazing Awareness Day.[21]Phi Beta Sigma’s efforts to eliminate hazing from the fraternity continue as local chapters are now mandated to participate in anti-hazing awareness workshops.

Notable hazing incidents[edit]

In 1992, a pledge at Southern University (Baton Rouge) went blind after being intentionally hit on the head with a frying pan by a member of the fraternity.[22]

In 1998, a pledge at Southern Illinois University was struck in the chest by several members of the fraternity which caused him to suffer from a severe asthma attack.[23]

In 2006, seven Sigmas were arrested for beating pledges from the University of South Carolina.[24] One known pledge was hospitalized due to the severe beatings and torment.

In 2009, Donnie Wade Jr., a student at Prairie View A&M University, died of extreme exhaustion due to illegal hazing activity while he was pledging the fraternity. His family filed a $97 million lawsuit against the fraternity and the chapter was temporarily expelled from campus for several years.[25][26]

In 2014, a former Francis Marion University student won a $1.6 million lawsuit against the fraternity after suffering acute renal failure due to being severely beaten throughout his pledge process. Nine Phi Beta Sigma members were arrested.[27]

In 2015, the fraternity was kicked off the campus of Salisbury University until Spring 2017. The university had received several anonymous complaints of pledges being beaten with paddles, forced to drink alcohol, and being harassed.[28]

Notable members[edit]

Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity’s membership includes many notable members who are involved in the fields of arts and entertainment, business, civil rights, education, health, law, politics, science, and sports. The fraternity’s membership roster includes heads of state Benjamin Nnamdi Azikiwe, Kwame Nkrumah, William Tolbert, and William V.S. Tubman, the past presidents of Nigeria, the Republic of Ghana, and Liberia respectively. Other notable members include world-famous scientist George Washington Carver, the first black Rhodes Scholar Alain LeRoy Locke, co-founder of the Black Panther Party Huey P. Newton, organizer of the Million Man March Benjamin Chavis Muhammad, civil rights activists Hosea Williams and the Rev. Al Sharpton, musicians The Original Temptations, actor Terrence Howard, television personality Al Roker, professional athletes Jerry Rice, Emmitt Smith, Hines Ward, Richard Sherman and Ryan Howard, the Philadelphia Phillies first baseman and award-winning actor Blair Underwood.[29]

International Presidents[edit]

Listed below are the thirty-four International Presidents[30] since the 1914 institution of the office

|

|

Conclave[edit]

The city of Little Rock, Arkansas served as the location of the Phi Beta Sigma’s 2015 Conclave.

The Conclave is the legislative power of Phi Beta Sigma. During a conclave year, delegates representing all of the active chapters from within the seven regions of the Fraternity meet in the chosen city. The Conclave-or fraternity convention- is currently held biannually and usually co-hosted by the alumni and collegiate chapters of the chosen city. During the convention, members of the General Board – the administrative body of the fraternity-are elected and appointed. The General Board may act in the interest of the Fraternity when the Conclave is not in session. In addition, seminars, social events, concerts, an international Miss Phi Beta Sigma Pageant, Stepshow, and oratorical contests are also held during the week-long conference. Throughout the years, notable individuals such as George Washington Carver, Dr. Carter G. Woodson, and NFL quarterback Charlie Batch were speakers at past Conclaves.

The Current General board is composed of The International President, First Vice-President, Second-Vice President, Treasurer, General Counsel, a Distinguished Service Chapter Representative, the regional directors, the immediate past-president, two collegiate members at large, and director of collegiate affairs. The offices of Second-Vice President and collegiate member at large are reserved positions on the general board for collegiate (undergraduate) members to hold. In addition, the Editor of The Crescent Magazine, Director of publicity, and the National Executive Director make up the members of the General Board. The latter-mentioned members are appointed to their positions and do not hold voting powers.

Distinguished Service Chapter members[edit]

Established at the 1929 Conclave, the Distinguished Service Chapter is the highest honor bestowed on a member of Phi Beta Sigma. Membership in the Distinguished Service Chapter must be recommended and approved by the awardees Chapter, Region, and by the General Board of the Fraternity prior to entry. One must meet the following criteria in order to be considered for this honor:

- Active in the Fraternity for at least ten years

- Has distinguished himself in the Fraternity and/or in his respective communities for extending exemplary service.

Brother Jesse W. Lewis holds the distinction of being voted in as the DSC’s 1st member (1929).

Regions[edit]

Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity organizes its chapters according to their regions in the United States and abroad. The seven regions are each led by a regional director and a regional board. A comprehensive list of regions is shown below:[31]

|

|

The national programs[edit]

| Bigger and Better Business | Project Vote |

| Project S.E.E.D. | Phi Beta Sigma Capitol Hill Summit |

| National Program of Education | Project S.A.T.A.P.P. |

| Project S.E.T. | Sigma Wellness Project |

| Project S.W.W.A.C. | The Sigma Beta Club |

| Clean Speech Movement | Sigma Academy |

| Sleepout For The Homeless | HIV/AIDS Awareness |

| Project S.A.D.A. | Project S.A.S |

| Project S.E.R. | Phi Beta Sigma National Marrow Donor Program |

| Sigma I.D. Day | Phi Beta Sigma – “A Fraternity that Reads” |

| Phi Beta Sigma – “Buying Black and Giving Back” |

Phi Beta Sigma aims their focuses on issues that greatly impact the African American community and the youth of the nation. The Phi Beta Sigma national programs of Bigger and Better Business, Education and Social Action are realized through the Fraternity’s overarching program, Sigma Wellness, adopted in 2007.[33]Through its national mentoring program for males ages 8–18, the organization provides opportunities for the development of young men as they prepare for college and the workforce.

The organization’s partnerships with the American Cancer Society, March of Dimes, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Boy Scouts of America and the Thurgood Marshall College Fund speaks to its mission to address societal ills including health disparities and educational and developmental opportunities for young males.

Bigger and Better Business[edit]

As told by Dr. I.L. Scruggs (excerpts from Our Cause Speeds On):

- “Philadelphia, 1924, Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity ‘arrived’. We had a mob of people at this Conclave. There were representatives from twenty-eight chapters -and all the trimmings. The introduction of the Bigger and Better Negro Business idea was made by way of an exhibit devoted to this topic.

- The Bigger and Better Negro Business idea was first tested in 1924 with an imposing exhibition in Philadelphia. This was held in connection with the Conclave. Twenty-five leading Negro Businesses sent statements and over fifty sent exhibits. The whole show took place in the lobby of the YMCA. Several thousand visitors seemed to have been impressed. The response was so great that the 1925 Conclave in Richmond, Virginia voted unanimously to make Bigger and Better Negro Business the public program of the Fraternity, and it has been so ever since.”

- Phi Beta Sigma believes that the improvement and economic conditions of minorities is a major factor in the improvement of the general welfare of society. It is upon this conviction that the Bigger and Better Business Program rests. Since 1926, the Bigger and Better Business Program has been sponsored on a national scale by Phi Beta Sigma as a way of supporting, fostering, and promoting minority owned businesses and services.[34]

The Bigger and Better Business serves as an umbrella for other national initiatives involving business. The program’s goals include supporting minority businesses, increasing communication with sigma brothers involved with business, and instilling sound business principals and practices to members of the community. Project S.E.E.D. (Sigma Economic Empowerment Development) is the foremost Bigger and Better Business Program. The program was developed to help the membership focus on two important areas: Financial Management and Home ownership.

Education[edit]

The founders of Phi Beta Sigma were all educators in their own right. The genesis of the Education Program lies in the traditional emphasis that the fraternity places on Education. During the 1945 conclave in St. Louis, Missouri, the fraternity underwent a constitution restructuring which led to the birth of the Education as a National Program.

The National Program of Education focuses on programming and services to graduate and undergraduates in the fraternity. Programs such as scholarships, lectures, college fairs, mentoring, and tutoring enhance this program on local, regional and national levels.[35]

Project S.E.T. (Sigma Education Time) is focused on increasing grade point averages and graduation rates of collegiates throughout the nation. The program aims to help with job readiness, choosing a career path {3–5 year outlook}, interviewing techniques, negotiating and entrepreneurship.

The Sigma Beta Club provides mentoring, guidance, educational tutorial assistance and advise to young men between ages 6 to 18. Created in 1950, it was the first youth auxiliary group of any of the National Pan-Hellenic Council organizations.

Social action[edit]

Phi Beta Sigma at the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Phi Beta Sigma has from its very beginning concerned itself with improving the general well-being of minority groups. In 1934, a well-defined program of Social Action was formulated and put into action. Elmo M. Anderson, then president of Epsilon Sigma Chapter (New York) formulated this program calling for the reconstruction of social order. It was a tremendous success. It fit in with the social thinking of the American public in those New Deal years.

In the winter of 1934, Sigma brothers Elmo Anderson, James W. Johnson, Emmett May and Bob Jiggets presented the Social Action proposition to the Conclave in Washington, D.C. The idea was adopted as a national program at the same conclave. Anderson is credited as “The Father of Social Action”.[36]

The fraternity’s five main social action programs are Project Vote, Sigma Wellness, Sigma Presence on Capitol Hill, and projects S.W.W.A.C. & S.A.T.A.P.P.

Project S.W.W.A.C. (Sigmas Waging War Against Cancer) is a concentrated and coordinated effort to reduce the incidence of cancer in the African American community. Through a partnership with the American Cancer Society, the goal of Project S.W.W.A.C. is to increase awareness, with a strong emphasis on early detection and prevention of prostate and colorectal cancer.[37] Project S.A.T.A.P.P. is a collaborative venture with the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation to address the alarming rise in teenage pregnancy. The Sigma Wellness Project is focused on living healthier lifestyles through education. The goal of Project Vote is to register and educate citizens and encourage members of the community to participate in the democratic process. The Sigma Presence on Capitol Hill Program is focused on presenting Sigma members the opportunity to discuss many of the critical issues facing our communities with members of the U.S. Congress.[37]

The Sigma Beta Club[edit]

In the early 1950s, Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity developed a youth auxiliary group. Under the direction of Dr. Parlett L. Moore the Sigma Beta Club was founded. While as National Director of Education, Brother Moore was concerned about our changing needs in our communities and recognized the important role that Sigma men could play in the lives of our youth. On April 23, 1954, the first club chapter was organized in Montgomery, AL. Throughout its existence, Sigma Beta Club has been an essential part of the total organizational structure of many of the Alumni chapters of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. and offers men of Sigma a unique opportunity to develop wholesome value, leadership skills, and social and cultural awareness of youth at a most critical stage in the youth’s personal development. The Sigma Beta Clubs’ principles of focus emphasize Culture, Athletics, Social and Educational needs. Sigma Beta Club programs are geared to meet the needs of its members, but at the same time provide them with a well-rounded outlook that is needed to cope with today’s society. Phi Beta Sigma is confident that investing in our youth today will produce effective leaders of tomorrow. Sigma Beta Clubs also provide services to youths in their communities. Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.’s interest in fostering the development of youth into effective leaders has been realized in the establishment of strong and productive Sigma Beta Club all across the country.

The Phi Beta Sigma History Museum[edit]

The Sigma History Museum was a traveling exhibition created in 2001 by Sigma brothers Mark Pacich, Louis W. Lubin, Jr. and Ahab El’Askeni. The museum’s initial goal was to dispel the discrepancies of the Fraternity’s history, by collecting as many newspaper articles, Crescent Magazines, Conclave Journals, autographs, pictures, etc., as possible. With the help of many Sigma members, in addition to families and friends of Sigmas brothers, some impressive artifacts of the history of the Fraternity were discovered. Among those artifacts, pictures of Sigma Founder A. Langston Taylor; historical pictures from the 1914, 1915, and 1916 yearbooks at Howard University; original letters; Conclave banners; and interviews with Sigma Brother Decatur Morse, son of Sigma Founder Leonard F. Morse, Samuel Proctor Massie II, son of a Alpha Chapter charter member, Samuel P. Massie, Robert L. Pollard II, son of Sigma brother Col. Robert L. Pollard who joined Sigma in 1919, and Dr. Gregory Tignor, son of Sigma brother Madison Tignor who also joined Sigma in 1919. The exhibit has been displayed in many cities including; Orlando, Philadelphia, Detroit, Memphis, and Las Vegas.

“Culture For Service and Service For Humanity”

Phi Beta Sigma Motto

On July 16, 2014, as part of the fraternity’s centennial celebration, a permanent museum was opened at the Phi Beta Sigma International Headquarters in Washington D.C. As a result, Phi Beta Sigma became the first Historically Black Greek Lettered fraternity to open its own museum.[38]

The assets of the museum have grown since the initial display in 2000. The most coveted possession yet to be acquired are the first 2 issues of the Phi Beta Sigma Journal. The museum is only 14 issues away from having every Crescent magazine ever printed.[39]