| Protests against Donald Trump | |||

|---|---|---|---|

From top to bottom:

Protestors in St. Paul, Minnesota, a protest near the United Nations Plaza in San Francisco, and Chicago, Illinois |

|||

| Location | United States, Canada, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Philippines, Australia, Israel, among other countries. | ||

| Causes |

|

||

| Methods | Demonstration, riots, Internet activism, political campaigning, vandalism, arson | ||

| Result |

|

||

| Number | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

| Injuries | 43+[7][8][9] | ||

| Arrested | 371+ [7] | ||

Protests against Donald Trump, or anti-Trump protests, have occurred both in the United States and worldwide following Donald Trump‘s 2016 presidential campaign, his electoral win, and through his inauguration.

Contents

- 1.Campaign protests

- 2.Post-election protests

- Protests during Trump’s campaign

- 2.12015

- 2.22016

- 2.2.1January

- 2.2.2February

- 2.2.3March

- 2.2.4April

- 2.2.5May

- 2.2.6June

- 2.2.7July

- 2.2.8August

- 2.2.9October

- 2.2.10November

- 2.2.11 December

- Protests during Trump’s campaign

- 3.Stop trump movement

- 4. Protests during Trump’s presidency

- 4.1. January

- 4.2.Inauguration protests

- 4.3.Women’s March

- 4.1 Organizers

- 4.2 National co-chairs

- 4.3 Policy platform

- 4.4 Washington, D.C.

- 4.4.6 Other U.S. locations

- 4.4.7.International

- 4.4.8. Response

- 4.4.6.1 Academics

- 4.4.6.2 Media

- 4.4.6.3 Politicians

- 4.4.6.4 Celebrities

- 4.4.6.5 Activists

- 5.Follow-up

- 6.Locations

- 7. Kennedy Airport protest

- 8. February 2017

- 8.1 Bodega protests

- 8.2 Protests on February 4, 2017

- 8.3 Protests on the weekend of February 11, 2017

- 8.4 Day Without Immigrants

- 9. March

- 9.1 Resist Trump Tuesdays

- 9.2 United Voices Rally

- 9.3.A Day Without a Woman

- 10. April

- 10.1.Tax Day March

- 10.2. March for Science

- 11.May 2017

- 12.June 2017

- 13.July 2017

- 14. August 2017

- 15. September 2017

- 16. November 2017

- 17. January 2018

Campaign protests

A number of protests against Donald Trump’s candidacy and political positions occurred during his presidential campaign, including at political rallies.

Political rallies

During his presidential campaign, activists occasionally organized demonstrations inside Trump’s rallies, sometimes with calls to shut the rallies down;[10][11][12] fueled by some of Trump’s language,[13] protesters began to attend his rallies displaying signs and disrupting proceedings.[14][15] Following Trump’s election to the presidency, students and activists organized larger protests in several major cities across the United States, including New York, Boston, Chicago, Portland, and Oakland. Tens of thousands of protesters participated,[16][17][18] with many chanting “Not my president!” to express their opposition to Trump’s victory in the Electoral College. (He lost the popular vote by a margin of 2.1 percent.)[19]

There were occasional incidents of verbal abuse or physical violence, either against protesters or against Trump supporters. While most of the incidents amounted to simple heckling against the candidate, a few people had to be stopped by Secret Service agents. Large-scale disruption forced Trump to cancel a rally in Chicago on March 11, 2016, out of safety concerns.

Many protesters were part of organized groups such as Black Lives Matter.[20][21] They sometimes attempted to enter the venue or engage in activities outside the venue. Interactions with supporters of the candidate may occur before, during, or after the event.[22] At times, protesters attempted to rush the stage at Trump’s rallies.[23] At times, protests turned violent and anti-Trump protesters have been attacked by Trump supporters; this violence has received bipartisan condemnation.[24] MoveOn.org, People for Bernie, the Muslim Students’ Association, Assata’s Daughters, the Black Student Union, Fearless Undocumented Alliance, and Black Lives Matter were among the organizations who sponsored or promoted the protests at the March 11 Chicago Trump rally.[10][25][26][27]

There were reports of verbal and physical confrontations between Trump supporters and protesters at Trump’s campaign events.[28][29]

Fake News

Fox News incorrectly reported on a Craigslist advertisement that claimed to pay people $15 per hour, for up to four hours, if they took part in protests against Trump.[30] The fact checking website PolitiFact.com, rated a separate story titled “Donald Trump Protester Speaks Out: ‘I Was Paid $3,500 To Protest Trump’s Rally'” as “100 percent fabricated, as its author acknowledges.”[31] Paul Horner, a writer for a fake news website, took credit for the article, and said he posted the deceitful ad himself.[32]

Trump’s reactions

During the campaign, Trump was accused by some of creating aggressive undertones at his rallies.[33] Trump’s Republican rivals blamed him for fostering a climate of violence, and escalating tension during events.[34] Initially, Trump did not condemn the acts of violence that occurred at many of his rallies, and indeed encouraged them in some cases.[35][36]

In November 2015, Trump said of a protester in Birmingham, Alabama, “Maybe he should have been roughed up, because it was absolutely disgusting what he was doing.”[37] In December, the campaign urged attendees not to harm protesters, but rather to alert law enforcement officers of them by holding signs above their head and yelling, “Trump! Trump! Trump!”[38]Trump has been criticized for additional instances of fomenting an atmosphere conducive to violence through many of his comments. For example, Trump told a crowd in Cedar Rapids, Iowa that he would pay their legal fees if they engaged a protester.[39]

On February 23, 2016, when a protester was ejected from a rally in Las Vegas, Trump stated, “I love the old days—you know what they used to do to guys like that when they were in a place like this? They’d be carried out on a stretcher, folks.” He added, “I’d like to punch him in the face.”[40][41][42] Following criticism from the media over his language toward protesters, Trump began to backtrack and started encouraging supporters at rallies to not injure any protesters. He also admitted at his San Jose rally that he was wrong to make such inflammatory comments in the past.[43]

Security

Fairly early in the campaign the United States Secret Service assumed primary responsibility for Trump’s security. They were augmented by state and local law enforcement as needed. When a venue was rented by the campaign, the rally was a private event and the campaign might grant or deny entry to it with no reason given; the only stipulation was that exclusion solely on the basis of race was forbidden. Those who entered or remained inside such a venue without permission were technically guilty of or liable for trespass.[21] Attendees or the press could be assigned or restricted to particular areas in the venue.[20]

In March 2016, Politico reported that the Trump campaign hired plainclothes private security guards to preemptively remove potential protesters from rallies.[44] That same month, a group calling itself the “Lion Guard” was formed to offer “additional security” at Trump rallies. The group was quickly condemned by mainstream political activists as a paramilitary fringe organization.

Timeline of protests against Donald Trump

The following is a timeline of protests against Donald Trump.

Protesters at the inauguration of Donald Trump

Protests during Trump’s campaign[edit]

2015[edit]

Protests against Trump began following the announcement of his candidacy in June 2015, especially after he said that illegal immigrants from Mexico were “bringing drugs, bringing crime, they’re rapists”.[1][2]

June[edit]

- June 17 – At Trump’s first rally in New Hampshire, three protesters entered the rally and held up signs. This was the first documented protest of the campaign.[3][4]

- June 29 – At a luncheon in Chicago, about 100 protesters gathered across from the City Club of Chicago to demonstrate.[1]

July[edit]

A protest against Trump at the future Trump International Hotel Washington, D.C. on July 9, 2015

- July 9 – In Washington, D.C., a group of protesters gathered outside of the future Trump International Hotel Washington D.C. to demonstrate and “call for a worldwide boycott of Trump properties and TV shows”.[5]

- July 10 – While Trump spoke at a Friends of Abe gathering, about 150 protesters gathered with signs and hitting piñatas made in Trump’s image. A smaller group of Trump supporters gathered near the protests and caused tension, with one Trump supporter beginning to jab at protesters.[6]

- July 12 – Protesters interrupted Trump at a speech in Phoenix, Arizona, with a large sign and were later escorted out while Trump supporters chanted “U-S-A!“.[7]

- July 23 – Trump arrived in Laredo, Texas, and was greeted by protesters while others gathered in support.[8]

August[edit]

- August 11 – About 150 protesters gathered in Birch Run, Michigan outside of a rally at the Birch Run Expo Center, gathered by the Democratic Party of Michigan due to what they called “anti-immigrant, anti-veteran statements” made by Trump.[9]

- August 25 – During a press conference, Univision anchor Jorge Ramos began to question Trump since before being called on. After being told “Sit down! you weren’t called” and “Go back to Univision”, Ramos continued to protest Trump’s plan to deport illegal immigrants and their children born into citizenship in the U.S. Trump motioned to his security, with Keith Schiller removing Ramos from the event. Trump later met with Ramos alone.[10][11][12]

September[edit]

- September 3 – Trump’s chief of security, Keith Schiller, was filmed punching a protester.[13]

October[edit]

- October 14 – In Richmond, Virginia, several clashes broke out between protesters and Trump supporters.[14]

November[edit]

- November 7 – Over 200 protesters, many of them Latino, demonstrated outside of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, where Trump was hosting Saturday Night Live.[15]

December[edit]

- December 4 – After being interrupted ten times during a speech in Raleigh, North Carolina, Trump ended his rally.[16]

- December 12 – Multiple protesters heckled Trump during a rally in Aiken, South Carolina.[17]

- December 22 – Trump’s speech was interrupted more than ten times at a rally in Grand Rapids, Michigan, with dozens of protesters being ejected. Trump characterized the protesters as “drugged out”, antagonized them by calling them “so weak for not fighting security”, and asked protesters why they interrupted him “in a group of 9,000 maniacs that want to kill them”.[18]

2016[edit]

January[edit]

Trump protest in Lowell, Massachusetts, January 2016

- January 4 – Protesters interrupted Trump several times in Lowell, Massachusetts, with some chanting support for Bernie Sanders and the Black Lives Matter movement.[19]

- January 8 – During Trump’s visit to Burlington, Vermont, about 700 protesters demonstrated in the City Hall Park.[20]

February[edit]

- February 27 – In Valdosta, Georgia, 30 Valdosta State University students were asked to leave a college venue leased by the Trump campaign for a speech.[21][22]

- February 29 – At a rally, veteran photojournalist Chris Morris was grabbed by his throat and thrown to the ground by a member of the Secret Service.[23]

March[edit]

Trump rally at UIC Pavilion in Chicago on March 11, 2016, immediately after news of Trump’s cancellation of attendance of the event. Many protesters cheer “Bernie!” to show their support for Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders.

- March 1 – Kashiya Nwanguma attended a Trump rally in Louisville, Kentucky, with two anti-Trump signs. She reported that Trump supporters ripped her signs away and shouted insults at her.[24]

- March 10 – As Trump was being led by police from a rally in Fayetteville, North Carolina, a protester was punched by a Trump supporter. Charges of assault and battery were filed by the Cumberland County Sheriff’s Office.[25][26][27] A protester being led by police from a rally in Fayetteville, North Carolina, was sucker punched by John McGraw, a Trump supporter. McGraw later told the media that the next time he saw the protester, “we might have to kill him.”[28]McGraw was subsequently charged with assault and battery.[25][27][29] On Meet the Press, Trump said that he had instructed his team to look into paying McGraw’s legal fees and said, “He obviously loves his country.”

2016 Donald Trump Chicago rally protest

On March 11, 2016, the Donald Trump presidential campaign cancelled a planned rally at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), in Chicago, Illinois, citing “growing safety concerns” due to the presence of thousands of protesters in and outside of his rally.[5][6]

Thousands of anti-Trump demonstrators responding to civic leaders’ and social media calls to shut the rally down had gathered outside the arena, and several hundred more filled seating areas within the UIC Pavilion, where the rally was to take place. When the Trump campaign announced that the rally would not take place, there was a great deal of shouting and a few small scuffles between Trump supporters and anti-Trump protesters.

Prelude[edit source]

Plans to protest the Trump rally were launched a week in advance by a variety of community and student groups who largely organized via social media. Some 43,000 undergraduate and graduate students had signed a petition asking UIC to cancel the rally by March 6.[7] That same day, Latino leaders in the city, led by Democratic U.S. Representative Luis Gutierrez of Chicago, issued a call to their constituents to join them in a protest outside of the UIC Pavilion, where the rally was to take place.[8] One of many student-based protests was first proposed by 20-year-old Chicago political activist and Bernie Sanders supporter Ja’Mal Green, who had posted to Facebook a week urging others to “get your tickets to this. We’re all going in!!!! #SHUTITDOWN.”[9] Green told reporters that the plan was for protestors to make noise when Trump appeared, “and then rush the stage.”[10] While “activist groups did try to disrupt the event, … many protesters said that they learned of the demonstrations on social media and went of their own accord.”[11]

MoveOn.org confirmed that it helped promote the protest and paid for printing protest signs and a banner.[9][12] Among those who took part in organizing the protest included members of the UIC faculty, People for Bernie, the Fearless Undocumented Association, Black Lives Matter, Assata’s Daughters, BYP100, College Students for Bernie, and Showing Up for Racial Justice, with “black, Latino and Muslim young people” at the “core” of the crowds of protesters.[13][14][15][16][17]

Incident[edit source]

Video of Trump rally at UIC Pavilion in Chicago on March 11, 2016 immediately after news of Trump’s cancellation of attendance of the event. Many protesters cheer “Bernie!” to show their support for Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders.

Voice of America video of the clashes at the UIC Pavilion

The protests had begun 24 hours prior to the event with a vigil outside of UIC Pavilion. The vigil lasted until the rally was scheduled to begin.[18]

Thirty minutes after the rally was scheduled to begin, a representative of the Trump campaign came on stage and announced that the rally was postponed. The crowd immediately cheered and chanted “We dumped Trump!” and “We shut it down!”[14] As Trump supporters shouted “We want Trump!”, arguments, several fistfights,[2] and small scuffles[19] broke out between the groups.[14] Two police officers and at least two civilians were injured during the protests. Five people were arrested, including Sopan Deb, a CBS News reporter who was covering Trump’s campaign.[2] Protesters said that they were protesting against racism and Trump’s policies.[20] Some of the demonstrators were also members of the group Black Lives Matter.[20][21][22] A smaller number of protesters were seen carrying flags representing various groups and countries, including Mexico.[23][24]

John Escalante, the interim superintendent of the Chicago Police Department (CPD), said about 300 officers were on hand for crowd control.[2] A CPD spokesman said the department had never told the Trump campaign that there was a security threat, and added that the department had sufficient manpower on the scene to handle any situation.[25]

The Trump campaign postponed the rally. The CPD and other law-enforcement authorities “were not consulted and had no role in canceling the event.”[19] Trump initially claimed he had conferred with Chicago Police but later said that he made the decision himself: “I didn’t want to see people get hurt [so] I decided to postpone the rally.”[26][27][28][29][30]

Arrests[edit source]

Four individuals were arrested and charged in the incident. Two were “charged with felony aggravated battery to a police officer and resisting arrest”, one was “charged with two misdemeanor counts of resisting and obstructing a peace officer”, and the fourth “was charged with one misdemeanor count of resisting and obstructing a peace officer”.[31] Sopan Deb, a CBS reporter covering the Trump campaign, was one of those arrested outside the rally. He was charged with resisting arrest;[32] Chicago police ultimately dropped the charges.[33]

Reactions and aftermath[edit source]

Voice of America video about Trump and Sanders’ responses to the postponed Chicago rally

After the event was postponed, Green described the cancellation of the event as a “win,” saying that “our whole purpose was to shut it down… we had to show him that our voice in civil rights was greater than his voice. The minority became the majority today.”[10] Mayor Rahm Emanuel praised the Chicago Police Department’s work to restore order.[2]

Trump blamed Sanders for the clashes in Chicago, insisting that the protesters were “Bernie’s crowd” and that a protester who charged the stage at an event in Dayton, Ohio the following day was a “Bernie person”, calling on Sanders to “get your people in line.”[12][34]Sanders subsequently denounced Trump as a “pathological liar” who leads a “vicious movement”, and said that “while I appreciate that we had supporters at Trump’s rally in Chicago, our campaign did not organize the protests.” Sanders blamed Trump for propagating “birther” conspiracy theories and for promoting “hatred and division against Latinos, Muslims, women and people with disabilities.”[34]

Presidential candidates[edit source]

Republican[edit source]

Rivals for the Republican presidential nomination criticized Trump. Senator Ted Cruz of Texas said, “When you have a campaign that affirmatively encourages violence, you create an environment that only encourages that sort of nasty discourse.”[35] John Kasich, Governor of Ohio, issued a statement saying, “Tonight, the seeds of division that Donald Trump has been sowing this whole campaign finally bore fruit, and it was ugly.”[2] Senator Marco Rubio of Florida attributed blame for the events at various parties, including the protesters, the media, and the Democratic Party, but “reserved his harshest words” for Trump, condemning him for inciting supporters who have punched and beaten demonstrators and likening him to “Third World strongmen”.[36]

Democratic[edit source]

Clinton, one of two Democratic presidential candidates in the 2016 election, said in a statement that the Trump campaign’s “divisive rhetoric” was of “grave concern” and said, “We all have our differences, and we know many people across the country feel angry. We need to address that anger together.”[37] The morning after the incident, Clinton said, “The ugly, divisive rhetoric we are hearing from Donald Trump and the encouragement of violence and aggression is wrong, and it’s dangerous. If you play with matches, you’re going to start a fire you can’t control. That’s not leadership. That’s political arson.”[38] Bernie Sanders, the other Democratic candidate, tweeted: “We will continue to bring people together. We will not allow the Donald Trumps of the world to divide us up.”[39]

Media[edit source]

Conservative media described protest actions as an infringement on Trump’s freedom of speech. National Review editor Rich Lowry called the protest an indefensible “mob action” and wrote that “the spectacle … will probably only help” Trump, since he “thrives on polarization and has sought to turn up the temperature of his rallies with his notorious suggestions that protesters should get roughed up.” Fox News host Jeanine Pirro characterized the protesters as “abject anarchists” who had infringed upon Trump’s right to free speech by “responding to activist calls at #SHUTITDOWN.”[40][41]

Other media outlets stated that such protest actions were predictable due to Trump’s rhetoric. Rachel Maddow of MSNBC said that Trump’s violent rhetoric at campaign rallies resulted in the escalation of tensions: “Anybody who tells you that there is no connection between the behavior of the mob at these events and the behavior of the man at the podium leading the mob at these events is not actually watching what he’s been saying from the podium.”[42] Jelani Cobb wrote in the New Yorker that “[t]he image of protesters clashing with Trump supporters in Chicago … is the logical culmination of what we’ve seen throughout his Presidential campaign” as “the idea of fighting to take the country back” promoted by Trump’s campaign “went from figurative to literal.”[43]

- March 12 – Thomas Dimassimo, a 32-year-old man, attempted to rush the stage as Trump was speaking at a rally in Dayton, Ohio. Dimassimo was stopped by Secret Service agents and subsequently charged with misdemeanor disorderly conduct and inducing panic.[37]

- March 13 – Trump refused to take responsibility for clashes at his campaign events, criticized protesters who have dogged his rallies, and demanded that police begin to arrest rally protesters.[38] His Kansas City rally was interrupted repeatedly by protesters in the arena while protesters outside the event were pepper sprayed by police.[39][40] In an effort to dissuade future protesters, Trump may begin to request that protesters be arrested “[b]ecause then their lives are going to be ruined.”[40]

- March 17 – During an interview with CNN, Trump predicted “you’d have riots” if were denied the Republican nomination despite having the most delegates at the convention.[41]

- March 18 – Between 500 and 600 people engaged in a standoff outside of a rally in Salt Lake City, Utah. Police officers formed a human barricade to separate the two groups, who largely remained nonviolent. Toward the end of the rally, protesters tore down a security tent at a Trump rally in Utah and threw rocks at rally attendees as they left. Two people unsuccessfully attempted to breach the entrance of the venue. Secret Service officers secured the inside of the venue and roughly 40 police officers in riot gear repelled the protesters from entering the building.[42] No arrests were made.[43][44]

- March 19 – Thousands of anti-Trump protesters in New York chanted “Fuck Trump!” and “Donald Trump! Go away!” as they rallied around the Trump International Tower building near 60th St. and Columbus Circle. The group was followed by dozens of NYPD officers who lined the streets with metal barricades and blocked the protesters path as they tried to cross busy intersections. After violence broke out, police pepper-sprayed the crowd, whom police refused to let cross the street.[45] During a simultaneous protest, protesters blocked a highway leading to Trump’s Fountain Hills, Arizona rally, leading to three arrests.[46] During a separate rally in Tucson, Arizona later that night, a black Trump supporter was arrested after punching and stomping a white protester who had donned a Ku Klux Klan hood.[47]

April[edit]

Protests in New York City on April 14, 2016. One banner reads “Fuck UR Wall”, denouncing Trump’s policy on immigration.

- April 14 – Hundreds of protesters gathered in a New York City Hyatt hotel against the wishes of the hotel staff.[48]

- April 28 – Several hundred protesters in Costa Mesa, California, clashed with police and Trump supporters outside the OC Fair & Event Center, where Trump was holding a rally. Seventeen people were arrested and five police cars were damaged.[49]

- April 29 – Around 1,000 to 3,000[50][51][52] protested in the area surrounding Burlingame, California, where Trump was to give a speech at the California GOP convention.[53] Protesters rushed security gates at one point.[54] Activists blocked a main intersection outside the event and vandalized a police car. Eventually, the police restored order in the area.[55] For safety reasons, Trump himself was forced to climb over a wall and enter through a back entrance of the venue.[56]

May[edit]

An effigy seen in San Diego on show of May 26, 2016, featuring Trump with the word “Bigot” taped on while wearing a sombrero and holding a Mexican flag

- May 1 – Thousands of May Day demonstrators marched in downtown Los Angeles on Sunday, some speaking out in support of workers and immigrants, others criticizing Trump. LAPD Sergeant Barry Montgomery told The Los Angeles Times that no one was arrested. Some protesters carried a big inflatable figure of Trump holding a Ku Klux Klan hood in his right hand.[57]

- May 7 – Protesters shouting “Love Trumps Hate” met Trump supporters before his second rally in Washington. Many protesters outside spoke out against Trump’s words and policy stances regarding women, Hispanics, and Muslims, including his plan to build a wall between the U.S. and Mexico. Later in the day, a group of protesters blocked a road near where Trump was supposed to speak, hoping to keep him from reaching the location. According to authorities, “a small number of arrests” were made.[58]

- May 24 – Following a rally in Albuquerque, New Mexico, protesters began throwing rocks and bottles at police and police horses, smashed a glass door at the convention center, and burned a number of Trump signs and flags, filling the street with smoke.[59][60] Video footage of the incident also showed protesters jumping on top of several police cars.[61]

- May 25 – Anti-Trump protesters were arrested after clashing with Trump supporters in Anaheim.[62]

- May 27 – Anti-Trump protesters clashed with Trump supporters and with police after a Trump rally ended in San Diego. Protesters waved Mexican flags and signs supporting Bernie Sanders.[63] Some protesters were arrested when they attempted to push past railings separating them from the Convention Center where Trump was speaking.[64] The clashes, largely verbal and resulting in no injuries or property damage, began after the Trump rally ended and his supporters poured into the street. Individuals on both sides shouted and threw trash and the occasional punch, but no injuries or property damage were reported. Police then declared the protest an illegal assembly and ordered the crowd to disperse. Further arrests were made when some members of the crowd failed to disperse. A total of 35 people were arrested in that protest.[63][64][65]

June[edit]

- June 2 – Protests and riots occurred outside a Trump rally in San Jose, California. During a series of protests, hundreds of anti-Trump protesters waving Mexican flags climbed on cars, and harassed supporters of Donald Trump. There were reports of violence including instances of bottles being thrown and assaults against Trump supporters.[66][67] A police officer was assaulted.[68][67][69] At least one American flag was burned by protesters.[70] Video footage went viral of a female Trump supporter being pelted by eggs thrown by protesters.[71]

- June 3 – Vox suspended writer Emmett Rensin for allegedly inciting anti-Trump violence at protests.[72]

- June 10 – Anti-Trump protesters and Trump supporters clashed outside a rally in Richmond, Virginia. One Trump supporter was punched and several protesters were pushed to the ground by police. Five people were arrested but only one was charged.

- June 16 – A photographer for the Dallas Advocate was hit on head with a rock that had been thrown from a crowd outside a Dallas rally that included both Trump supporters and protesters.[73]

- June 19 – During a rally in Las Vegas, Michael Sandford, a 19-year-old British national, was arrested for assault and held in the county jail until he was arraigned in federal court and charged with “an act of violence on restricted grounds”. He was accused of attempting to seize a police officer’s firearm and later claiming he intended to kill Trump. A British citizen, he was in the U.S. illegally and is being held without bond.[74][75] He has since then pleaded guilty to federal charges of being an illegal alien in possession of a firearm and disrupting an official function.[76]

July[edit]

- July 1 – Three people were arrested after a conflict occurred between Trump supporters and anti-Trump protesters outside the Western Conservative Summit. According to The Gazette, a man grabbed pro-Trump bumper stickers from a woman selling them outside Denver‘s convention center, ripped some of them, and threw them in her face. A pushing match then ensued, with many people spilling into the street.[77]

August[edit]

- August 4 – Protesters stood silently among seated attendees at a Portland, Maine Trump rally, and held up pocket Constitutions, in reference to Khizr Khan‘s DNC speech days earlier. The protesters were ejected from the rally.[78]

- August 19 – Protesters harassed, pushed, and spit on Trump supporters outside a fundraising event in Minneapolis.[79]

- August 31 – A group of approximately 500 people protested in downtown Phoenix, Arizona chanting and hitting a Trump piñata. There were no arrests, although police had to usher two anti-Trump protesters off the sidewalk where speech-goers for a Trump rally entered the Phoenix Convention Center, saying that the protesters were causing conflict with the Trump supporters.[80]

October[edit]

- October 10 – Dave Eggers and Jordan Kurland launched the all-star music project 30 Days, 30 Songs, scheduled to publish one song per day advocating against Donald Trump.[81][82] Due to overwhelming response of more artists, the project was meanwhile renamed and rescheduled to 30 Days, 40 Songs and 30 Days, 50 Songs. Musicians include stars like R.E.M., Moby, Franz Ferdinand, Jimmy Eat World, Loudon Wainwright and many others.

GrabYourWallet

#GrabYourWallet (also, Grab Your Wallet)[1] is an organization and social media campaign that is an umbrella term for economic boycotts against companies that have any connections to President Donald Trump in response to the leak of a lewd conversation between Donald Trump and Billy Bush on the set of Access Hollywood where he infamously said “grab them by the pussy”.[2][3] The movement has particularly targeted the ride-sharing app Uber and President Trump’s daughter Ivanka Trump‘s clothing and shoe line that was notably carried by Nordstrom before being indefinitely discontinued due to poor sales as a result of the boycott.

History[edit source]

GrabYourWallet founder Shannon Coulter speaks at Day Without a Woman San Francisco, March 2017.

GrabYourWallet started on October 11, 2016 via Twitter by a San Francisco marketing strategist named Shannon Coulter,[1][6][7] with the help of Sue Atencio.[8] Coulter created a list of stores that carried Trump products after the Access Hollywood tape came out.[6] The news from the tape made Coulter physically ill for a few days.[9] Coulter went on Twitter where she was able to talk about her “deep ambivalence” about spending money at a place that sold Trump products.[9] She stated that she wanted “to be able to shop with a clear conscience,”[7] and did not feel comfortable purchasing items from those who do business with anyone in the Trump family.[10] The name, “GrabYourWallet” is a reference to both Trump’s comments about women and people using their buying power to influence companies.[10]Coulter emphasizes that the movement is non-partisan and says, “This is a human decency thing. It’s about the divisiveness and disrespectfulness of Donald Trump.”[11]

Within a month, one company, Shoes.com, dropped Ivanka Trump‘s brand from their website.[12] Interior design company, Bellacor, dropped the Trump Home brand in November.[13] Both of these companies did contact supporters of the boycott campaign after dropping the Trump lines.[13] By February 2017, 18 companies had stopped carrying Trump brand merchandise.[11]

After Trump was elected President, Coulter created a spreadsheet of companies that do business with Trump family members and distributed the information online and via social media.[1] The sheet also provides alternatives to stores on the boycott list,[14] and has contact information so that consumers can “express their outrage.”[15] #GrabYourWallet as a movement grew larger after the election.[14][8]Part of the reason is that the campaign became part of the broader anti-Trump movement.[2] Working on the campaign has almost become a full time job for Coulter.[2]

Nancy Koehn of Harvard Business School told PBS NewsHour that though boycotting business is not new, the scope of #GrabYourWallet is unprecedented.[10] She also said that the boycott is unique because it is in “resistance or opposition to the current administration.”[10]

On Twitter, more than a combined 626 million impressions have amassed.[16] Twitter users use the hashtag, #GrabYourWallet and some independently tweet at businesses carrying Trump merchandise.[6] Captiv8, a social media influence study group, has found that most engagements with the hashtag come from California and New York.[2]

Counter-boycotts[edit source]

Forbes dubbed it the “Trump effect” and “GrabYourWallet effect”, given that when people boycott companies, his supporters pledge to start buying those products and vice versa.[15][17] Trump supporters started boycotting Nordstrom after they dropped Ivanka Trump’s line of clothes.[10]

Supporters of Trump took to Amazon.com to make Ivanka Trump’s fragrance the best selling fragrance on the site for a week.[18]

Notable boycott targets[edit source]

Uber[edit source]

The app Uber was targeted for its alleged relation to Executive Order 13769 which has also been referred to as “Muslim ban”.[19] As taxi drivers to JFK Airport went on strike in solidarity with Muslim refugees, Uber removed surge pricing to the airport where Muslim refugees had been detained upon entry. Uber was also targeted because CEO Travis Kalanick was on an Economic Advisory Council with President Trump.[20] As a result, a social media campaign called #deleteuber arose and approximately 200,000 users deleted the app.[21] This campaign made Kalanick resign from the Council.[22] An email with a statement sent to who deleted their accounts stated that the company would be assisting refugees and that CEO Kalanick did not join the Council as an endorsement of President Trump.[23]

Ivanka Trump[edit source]

Ivanka Trump, 2016

In the beginning of the proposed boycott, Nordstrom stated that if costumers stopped buying Ivanka Trump‘s line, as a business decision they would stop carrying it (which they did in February 2017). Nordstrom also acknowledged that customers would counter-boycott if they dropped the line.[24] Before the inauguration of President Trump, Ivanka Trump had announced she would be resigning from her fashion brand.[25] Sales of Ivanka Trump’s line started falling before the 2016 election.[26] And in February 2017 President Trump expressed his ire at Nordstrom via Twitter and White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer called the business decision a “direct attack on President Trump”.[27] President Trump’s tweet caused Nordstrom’s shares to temporarily fall, before soaring by 7%.[28]

Macy’s customers have also asked that the company drop Ivanka Trump’s line.[29]

Ivanka Trump also faced criticism from Coulter when she promoted her $10,800 gold bracelet to fashion writers after wearing it on an interview about her father on 60 Minutes.[8]

Controversy[edit source]

In February 2017, President Trump’s spokeswoman Kellyanne Conway formally endorsed Ivanka Trump’s products on Fox News by saying she is giving the brand a “free commercial” telling viewers to buy Ivanka Trump’s products.[30] The statement was seen as a violation of federal ethics laws.[31]

[edit source]

Primary targeted companies[edit source]

[edit source]

These companies have been identified by grabyourwallet.org as companies that will not be boycotted though they have a connection to President Trump or family members business.[32]

- Washington Post is owned by Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon.com (which indirectly sells Trump products), but the Washington Post has not been targeted since it did critical reporting of President Trump.[2]

- Facebook has not been targeted because the scope of its user base and CEO Mark Zuckerberg has criticized President Trump.

- Home Depot is not being boycotted because it discontinued sales of Trump Home products.

- Delta Airlines has not been targeted because they do not directly have any business ties to President Trump, though there have been political controversies with certain passengers aboard Delta flights.

- Paypal has not been directly targeted, though co-founder Peter Thiel has endorsed Trump, because he is no longer involved with the company.

- Carrier Corporation has not been boycotted, though then-president-elect Trump got directly involved in keeping 1,000 jobs from moving to Mexico, because they don’t do monthly or continued business with any Trump family member.

Companies that cut ties with Trump family as result[edit source]

- October 18 – Dozens of women, some of whom were victims of sexual assault, gathered in front of Trump Tower on a Tuesday morning to begin a series of protests across the nation pushing women to leave the Republican party and un-endorse Donald Trump. Dressed in black, the protesters sat in front of Trump Tower holding signs such as “Grab my pussy, muthafucker I dare you” and “Don’t tread on my pussy”.[84]

- October 26 – Trump’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame was destroyed with a sledgehammer and a pickaxe.[85]

November[edit]

- November 5 – During a rally at the Reno-Sparks Convention Center in Reno, Nevada, Trump was rushed off stage by Secret Service agents when someone yelled “gun” while others tried to take a protester’s anti-Trump sign. The protester was questioned and found to have no weapons on him. Trump returned minutes later to resume his rally.[86][87]

Post-election protests[edit]

Following the announcement of Trump’s election victory, large protests broke out across the United States including other countries such as Canada, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Philippines, Australia, Israel with some continuing for several days, and more protests planned for the following weeks and months.

November 2016[edit]

Protest outside Trump Tower, Chicago on November 9, 2016

- November 9

| Protests against Donald Trump that occurred in cities on November 9, 2016 |

|---|

|

Dallas,

Reno,

|

According to several sources, thousands of protesters took to the street in Chicago. Chicago Tribune explains that the protest was “relatively peaceful” and was “devoid of any of the heavy vandalism of effigy burning that occurred elsewhere.” Five people were arrested altogether.[88][89][90]

- Atlanta, Georgia,

- Boston, Massachusetts,

- Cleveland, Ohio,

- Dallas, Texas,

- Detroit, Michigan,

- Houston, Texas,

- Los Angeles, California,

- Miami, Florida,

- New York City, New York,

- Oakland, California,

- Omaha, Nebraska,

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

- Portland, Oregon,

- Richmond, Virginia,

- San Diego, California,

- San Francisco, California,

- San Jose, California,

- Seattle, Washington,

- Washington, D.C.,

- Winston-Salem, North Carolina,

Protests also occurred at various universities, including:

High school and college students walked out of classes to protest.[97][113] The protests were mostly peaceful, although at some protests fires were lit, flags were burned, and a Trump piñata was burned.[114][115][116] Celebrities such as Madonna, Cher, and Lady Gaga took part in New York.[117][118][119] Some protesters took to blocking freeways in Los Angeles, San Diego, and Portland, Oregon, and were dispersed by police in the early hours of the morning.[120][121] One protester was hit by a car.[122] In a number of cities, protesters were dispersed with rubber bullets, pepper spray and bean-bags fired by police.[123][124][125] While protests ended at 3:00 a.m. in New York City, calls were made to continue the protests over the coming days.[126]

- November 10

Protests in Madison, Wisconsin

“Love Trumps Hate” was a common slogan, as here at the Idaho State Capitol.

As Trump held the first transition meeting with President Obama at the White House, protesters were outside.[127] Protests continued in cities across the United States. International protests were held in London, Vancouver, and Manila.[128][129]Former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani called protesters “a bunch of spoiled cry-babies.”[130] Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti expressed understanding of the protests and praised those who peacefully wanted to make their voices heard.[131]

In Austin, Texas, a young girl rallied protesters behind the mantra: “I am a female, I am mixed race, I am a child and I cannot vote. But that will not stop me from getting heard” after which chants of “Love is love, and love trumps hate” followed.[132][133][134][135] In Los Angeles, protesters continued blocking freeways.[136] A peaceful protest turned violent when a small group began rioting and attacking police in Portland, Oregon.[137] The protests in Portland attracted over 4,000 people and remained largely peaceful, but took to the highway and blocked traffic.[138] Acts of vandalism including a number of smashed windows, vandalized vehicles, and a dumpster fire caused police to declare a riot.[138][139] Protesters tried to retain the peaceful nature of the protest and chanted “peaceful protest”.[140]

Protests were held in the following cities:

- Chicago, Illinois,

- Dallas, Texas,

- Grand Rapids, Michigan,

- Greensboro, North Carolina,

- Louisville, Kentucky,

- Madison, Wisconsin,

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin,

- Minneapolis, Minnesota,

- New York City, New York,

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

- Pittsburg, California,

- Portland, Oregon,

- Richmond, Virginia,

- Tampa, Florida,

Numerous petitions were started to prevent Trump from taking office; including a Change.org petition started by Elijah Berg of North Carolina requesting that faithless electors in states that Trump won vote for Clinton instead, which surpassed three million signatures.[151]

- November 11

Protests occurred in the following cities:

- Anchorage, Alaska,

- Atlanta, Georgia,

- Bakersfield, California,

- Burlington, Vermont,

- Columbia, South Carolina,

- Columbus, Ohio,

- Dallas, Texas,

- Denver, Colorado,

- Des Moines, Iowa,

- Eugene, Oregon,

- Fort Worth, Texas,

- Grand Rapids, Michigan,

- Iowa City, Iowa,

- Los Angeles, California,

- Nashville, Tennessee,

- New Haven, Connecticut,

- New York, New York,

- Olympia, Washington,

- Orlando, Florida,

- Royal Oak, Michigan,

- San Antonio, Texas ,

Protests also occurred at the following schools:

- Ohio State University,

- State University of New York at New Paltz,

- Texas State University,

- University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,

- University of Massachusetts Amherst,

- University of Miami,

- University of North Carolina, Greensboro,

- University of North Carolina, Wilmington,

- University of Pacific,

- University of Rochester,

- Vanderbilt University,

- Virginia Commonwealth University,

- Wayne State University,

- Wesleyan University,

A protest also occurred at the U.S. embassy in Tel Aviv, Israel.[185][186] The American and Mexican national soccer teams also posed together in a Unity Wall in response to Trump’s election before their World Cup qualifying match in Columbus, Ohio.[187]

Michael Moore at the march against Trump, New York City, 12 November 2016

- November 12

News report about the protests in Los Angeles on November 12 from Voice of America

During a peaceful march in Oregon in the early hours of November 12, one protester was shot by an unknown assailant.[188] Police in Portland, Oregon, said that they arrested over than twenty people after protesters refused to disperse.[189]

Protesters at an anti-Trump rally in Indianapolis on November 12th

On the first weekend day after the election, a march of over 10,000 people in Los Angeles went from MacArthur Park and shut down the busy Wilshire Blvd corridor.[190][191] In New York City, another crowd cited by NBC News as 25,000[192]marched from Union Square to Trump Tower.[193][194][195] In Chicago, thousands of people marched through The Loop.[196] In Indianapolis, about 500 people gathered at the Statehouse, then proceeded to march downtown.[197] Protesters split off into several groups, some of which moved to the streets and blocked traffic.[198] Some protesters were allegedly throwing rocks at police officers, who responded by firing non-lethal weapons.[199]

International protests also occurred in cities such as Berlin, Germany, Melbourne, Australia and Perth, Australia and Auckland, New Zealand.[200][201][202][203]

- November 13

Protests continued in the following cities:

- Chicago, Illinois,

- Denver, Colorado,

- Erie, Pennsylvania,

- Fort Lauderdale, Florida,

- Los Angeles, California,

- Manchester, New Hampshire,

- New Haven, Connecticut,

- New York City, New York,

- Oakland, California,

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

- Royal Oak, Michigan,

- San Francisco, California,

- Springfield, Massachusetts,

- San Antonio, Texas ,

International protests have occurred in cities including Toronto, Canada, where about a thousand people gathered in Nathan Phillips Square.[209][210]

- November 14

Anti-Trump protest in Silver Spring, Maryland[211]

A group of 40 protesters in Washington, D.C. staged a sit-in at the office of prospective Senate minority leader Charles Schumer, in an effort to change Democratic leadership and prevent the party’s collaboration with Trump. Seventeen arrests were made at that sit-in.[212]

At a small protest at Ohio State University, protest leader Timothy Adams was attacked from behind and knocked down to the steps he was standing on, breaking his bullhorn and glasses.[213][214]

Several school districts experienced walkouts from high school students, many of them too young to have voted.[215]

- November 15

Wilson High School students protest outside Trump Hotel in Washington, D.C. News report from Voice of America.

Protests occurred in the following cities and universities:

-

- Akron, Ohio,

- Beltsville, Maryland,

- Kalamazoo, Michigan,

- Montgomery County, Maryland,

- New York City,

- Santa Barbara, California,

- Washington, D.C.,

- La Salle University,

- Penn State University,

- Rutgers University,

- St. Mary’s College of California,

- Stanford University,

- University of California, Riverside,

- University of Chicago,

- University of Illinois at Chicago,

Protesters in Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey

- November 16

Student protests continued for a third day in Montgomery County, Maryland.[219]

Students around the country walked out of classes in an effort to push their schools to declare themselves a “sanctuary campus” from Trump’s planned immigration policy of mass deportations.[231] The Stanford, Rutgers, and St. Mary’s protests on November 15 were among the first.[226] Rutgers President Robert Barchi responded that the school will protect the privacy of its undocumented immigrants.[232] California State University Chancellor Timothy P. White made a similar affirmation.[233] Iowa State University reaffirmed continuation of their already existing policy.[234]

Around 350 Harvard University faculty members signed a letter urging the administration to denounce hate speech, protect student privacy, reaffirm admissions and financial aid policies and to make the university a sanctuary. One of the first to sign the letter was Henry Louis Gates Jr.[235]

The letters of Trump’s name were removed from three buildings in Manhattan, including Trump Place due to angered residents.[236]

- November 17

Protest in Mission District, San Francisco, California on November 17

-

- In the early morning in Los Angeles, protesters chanted “Fire Bannon” in reference to Trump appointing Steve Bannon as chief White House strategist and senior counselor on Sunday.[237][238] Bannon denied accusations of his being a white nationalist, saying “I’m a nationalist.”[239][240]

- Two students were arrested at a protest at the University of Pittsburgh[241]

- A rally was held at the University of Miami[242]

- Around 100 students protested at Portland State University[243]

- November 18

Anti-Trump protest in Chapel Hill, North Carolina on November 18

Various protests occurred in Augusta, Maine,[244] Chapel Hill, North Carolina,[245]Cleveland, Ohio,[246][247] Prince George’s County, Maryland,[248] Sacramento, California,[249] and Washington, D.C.[250]

Vice President-elect Mike Pence attended the musical Hamilton in New York City, where he was addressed by the cast.[251]

- November 19

Protesters in Chicago on November 19, Marching toward Trump Tower Chicago

Philadelphia anti-Trump Rally on November 19, 2016

-

- About 3,000 formed a hand holding ring around Green Lake in Seattle, Washington.[252]

- In Chicago, approximately 2,000 protesters marched from Federal Plaza to Trump Tower Chicago.[253][254][255][256]

- Several hundred protesters rallied and marched in downtown San Francisco.[257]

- In New York City, three separate protests converged on the heavily secured area surrounding Trump Tower in New York City, where security guided them into a demonstration pen that had been erected outside of the president elect’s offices and residence. One group marched from Queens.[258] One group protesting Trump’s appointment of Bannon marched from Washington Square Park. A smaller but more dramatic group wearing stage special effects makeup of wounds and scars, marched from Union Square to indicate the damage a Trump administration will have on “marginalized people” including women.[259]

- International protests occurred in Toronto, Canada;[260] Melbourne, Australia;[261] and Paris, France.[262]

- November 20

-

- A 69-year-old man dressed in a U.S. Marine uniform set himself alight in the Highland Square in Akron, Ohio, after ranting about the need to protest Trump’s election. He was hospitalized in stable condition.[263][264]

- A protest in Brooklyn Heights attracted Adam Horovitz to Adam Yauch Park (a park named after his late-Beastie Boys bandmate), where multiple spray-painted swastikas and the message “Go Trump” had been discovered two days before.[265] At the protest, Horovitz released a statement against Trump.[266]

- An anti-Trump group called “Not Up For Grabs: Portland” marched in Portland, Oregon.[267]

- During a live performance on the American Music Awards of 2016, Green Day performed their new song Bang Bang. In the middle of the song, lead singer Billie Joe Armstrong included the anti-Trump chant “No Trump, no KKK, no fascist USA!”[268]

- November 21

-

- A rally was held outside the Rhode Island State House in Providence, Rhode Island.[269]

- A protest was held in front of the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, Ohio.[270]

- Protests continued outside Portland City Hall in Portland, Oregon, and a march was held later in the evening.[271]

- November 22

Students at Christopher Newport University protested.[272]

- November 23

Protest in Minneapolis, Minnesota on November 23

A protest occurred in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The protesters called for President Obama to pardon all immigrants before the end of his term.[273]

- November 25

On Black Friday, protesters blocked entrances to stores on the Magnificent Mile in Chicago.[274]

- November 26

A small protest occurred at Pioneer Courthouse Square in Portland, Oregon. Protester Bobby Lang said, “It’s either sit in horror or go out and do things.”[275]

- November 27

A protest occurred at the Nebraska State Capitol building.[276] The crowd was estimated at around 200 people.[277]

December 2016[edit]

- December 8 – There was controversy about the inaugural permitting for protests.[278] Hundreds of thousands of people have organized on Facebook to attend.[279] Partnership for Civil Justice Fund for the A.N.S.W.E.R. Coalition has a lawsuit pending about protest near the Trump Hotel.[280]

- December 18 – On International Migrants Day approximately 2,000 people marched peacefully in downtown Los Angeles against Trump’s policies on immigration, the environment and healthcare.[281]

- December 19 – On the day the United States Electoral College convened protests were held at numerous state capitols, including but not limited to those of Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Tennessee,[282] and Idaho.

International reactions

China – On November 14, 2016, the Chinese Consulate in San Francisco warned “Chinese exchange students, visiting students, teachers and volunteers” to avoid participating in the protests.[54]

China – On November 14, 2016, the Chinese Consulate in San Francisco warned “Chinese exchange students, visiting students, teachers and volunteers” to avoid participating in the protests.[54] Turkey – The Government of Turkey warned its citizens who may be traveling to the United States to “be careful due to protests” and that occasionally “the protests turn violent and criminal while protesters [are] detained by security forces” while also stating that “racists and xenophobic incidents increased in USA”.[55]

Turkey – The Government of Turkey warned its citizens who may be traveling to the United States to “be careful due to protests” and that occasionally “the protests turn violent and criminal while protesters [are] detained by security forces” while also stating that “racists and xenophobic incidents increased in USA”.[55]

Stop Trump movement

The Stop Trump movement, also called the anti-Trump, Dump Trump, or Never Trump movement,[1] was the informal name for the effort on the part of some Republicans and other prominent conservatives to prevent front-runner and now President of the United States Donald Trump from obtaining the Republican Party presidential nomination, and, following his nomination, the presidency, for the 2016 United States presidential election. Although Trump’s campaign drew a substantial amount of criticism, he was ultimately sworn in as president.

The movement gained momentum following Trump’s wins in the March 15, 2016, Super Tuesday primaries, including his victory over U.S. Senator Marco Rubio in Florida.[2][3][4][5] After U.S. Senator Ted Cruz dropped out of the race following Trump’s primary victory in Indiana on May 3, 2016, Trump became the presumptive nominee, while internal opposition to Trump remained as the process pivoted towards a general election.[6]

Following unsuccessful attempts by some delegates at the Republican National Convention to block his nomination, Trump became the Republican Party’s 2016 nominee for President of the United States on July 18, 2016. Some members of the Stop Trump movement endorsed alternative candidates in the general election, such as Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, Libertarian nominee Gary Johnson, independent conservative Evan McMullin, and American Solidarity Party nominee Mike Maturen.[7][8]

These efforts ultimately failed when Trump won the general election on November 8. According to exit polls, Trump received 90% of the GOP vote, while Clinton won 89% of Democratic voters.[9]

Background[edit]

Trump entered the Republican primaries on June 16, 2015, at a time when Governors Jeb Bush and Scott Walker and Senator Marco Rubio were viewed as the early frontrunners.[10] Trump was generally considered a longshot to win the nomination, but his large media profile gave him a chance to spread his message and appear in the Republican debates.[11][12] By the end of 2015, Trump was leading the Republican field in national polls.[13] Despite Trump’s enduring strength in the polls, his rivals continued to attack each other rather than Trump.[14] In this atmosphere, some Republicans, such as former Mitt Romney adviser Alex Castellanos, called for a “negative ad blitz” against Trump,[14] and another former Romney aide founded Our Principles PAC to attack Trump.[15] After Trump won the New Hampshire and South Carolina primaries, many Republican leaders called for the party to unite around a single leader to stop Trump’s nomination.[16]

Erickson meeting[edit]

On March 17, 2016, notable conservatives under the leadership of Erick Erickson met at the Army and Navy Club in Washington D.C. to discuss strategies for preventing Trump from securing the presidential nomination at the Republican National Convention in July. Among the strategies discussed were a “unity ticket”,[17] a possible third-party candidate and a contested convention, especially if Trump did not gain the 1,237 delegates necessary to secure the nomination.[18]

The meeting was organized by Erick Erickson, Bill Wichterman, and Bob Fischer. Around two dozen people attended.[19][20]Consensus was reached that Trump’s nomination could be prevented, and that efforts would be made to seek a unity ticket, possibly comprising U.S. Senator Ted Cruz and Ohio Governor John Kasich.[19]

Efforts[edit]

By political organizations[edit]

Our Principles PAC and Club for Growth were involved in trying to prevent Trump’s nomination. Our Principles PAC has spent more than $13 million on advertising attacking Trump.[21][22] The Club for Growth spent $11 million in an effort to prevent Trump from becoming the Republican Party’s nominee.[23]

By Republican delegates[edit]

In June 2016, activists Eric O’Keefe and Dane Waters formed a group called Delegates Unbound, which CNN described as “an effort to convince delegates that they have the authority and the ability to vote for whomever they want.”[24][25][26] The effort involved the publication of a book, Unbound: The Conscience of a Republican Delegate by Republican delegates Curly Haugland and Sean Parnell. The book argues that “delegates are not bound to vote for any particular candidate based on primary and caucus results, state party rules, or even state law.”[27][28]

Republican delegates Kendal Unruh and Steve Lonegan led an Free the Delegates effort among fellow Republican delegates to change the convention rules “to include a ‘conscience clause’ that would allow delegates bound to Trump to vote against him, even on the first ballot at the July convention.”[29] Unruh described the effort as “an ‘Anybody but Trump’ movement”. According to The Washington Post, Unruh’s efforts started with a conference call on June 16 “with at least 30 delegates from 15 states”. Regional coordinators for the effort were recruited in Arizona, Iowa, Louisiana, Washington and other states.[30] By June 19, hundreds of delegates to the Republican National Convention calling themselves Free the Delegates had begun raising funds and recruiting members in support of an effort to change Party convention rules to free delegates to vote however they want – instead of according to the results of state caucuses and primaries.[31] Unruh, a member of the convention’s Rules Committee and one of the group’s founders, planned to propose adding the “conscience clause” to the convention’s rules effectively unhinging pledged delegates. She needed 56 other supporters from the 112-member panel, which determines precisely how Republicans select their nominee in Cleveland.[32] However, the Rules Committee voted down, by a vote of 84–21, a move to send a “minority report” to the floor allowing the unbinding of delegates, thereby defeating the “Stop Trump” activists and guaranteeing Trump’s nomination. The committee then endorsed the opposite option, voting 87–12 to include rules language specifically stating that delegates were required to vote based on their states’ primary and caucus results.[33]

By individuals[edit]

At a luncheon in February 2016 attended by Republican governors and donors, Karl Rove discussed the danger of Trump securing the Republican nomination in July, and that it may be possible to stop him, but that there was not much time left.[34][35]

Early in March 2016, Mitt Romney, the 2012 Republican presidential nominee, directed some of his advisors to look at ways to stop Trump from obtaining the nomination at the Republican National Convention (RNC). Romney also spoke publicly urging voters to vote for the Republican candidate most likely to prevent Trump from acquiring delegates in state primaries.[36] A few weeks later, Romney announced that he would vote for Ted Cruz in the Utah GOP caucuses. On his Facebook page, he posted “Today, there is a contest between Trumpism and Republicanism. Through the calculated statements of its leader, Trumpism has become associated with racism, misogyny, bigotry, xenophobia, vulgarity and, most recently, threats and violence. I am repulsed by each and every one of these.”[37][38][39] Nevertheless, Romney said early on he would “support the Republican nominee,” though he didn’t “think that’s going to be Donald Trump.”[40]

U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham shifted from opposing both Ted Cruz and Donald Trump, to eventually supporting Cruz as a better alternative to Trump. Commenting about Trump, Graham said “I don’t think he’s a Republican, I don’t think he’s a conservative, I think his campaign’s built on xenophobia, race-baiting and religious bigotry. I think he’d be a disaster for our party and as Senator Cruz would not be my first choice, I think he is a Republican conservative who I could support.”[41][42]In May, after Trump became the presumptive nominee, Graham announced he would not be supporting Trump in the general election, stating “[I] cannot, in good conscience, support Donald Trump because I do not believe he is a reliable Republican conservative nor has he displayed the judgment and temperament to serve as Commander in Chief.”[43]

In October 2016, some individuals made third-party vote trading mobile applications and websites to help stop Trump; for example a Californian that wants to vote for Clinton will instead vote for Jill Stein, and in exchange a Stein supporter in a swing state will vote for Clinton.[44] The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in the 2007 case Porter v. Bowen established vote trading as a First Amendment right.

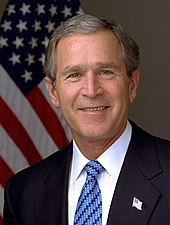

Former Republican Presidents George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush both refused to support Trump’s candidacy in the general election.[45][46]

List of Republicans who opposed the Donald Trump presidential campaign, 2016

Public officials[edit]

Former Presidents[edit]

Former President George H. W. Bush

Former President George W. Bush

- George H. W. Bush, President of the United States (1989–93); Vice President of the United States (1981–89)[1][2]

- George W. Bush, President of the United States (2001–09); Governor of Texas (1995-2000)[3]

Former 2016 Republican presidential primary candidates[edit]

All candidates signed a pledge to eventually support the party nominee. The following have refused to honor it.

- Jeb Bush, Governor of Florida (1999–2007)[4]

- Carly Fiorina,[a][b] CEO of Hewlett-Packard (1999–2005); 2010 nominee for U.S. Senator from California[5][6]

- Lindsey Graham, United States Senator from South Carolina (2003–present) (voted for Evan McMullin)[7]

- John Kasich, Governor of Ohio (2011–present); U.S. Representative from Ohio (1983–2001)[8] (wrote in John McCain)[9]

- George Pataki, Governor of New York (1995–2006)[10]

Former federal cabinet-level officials[edit]

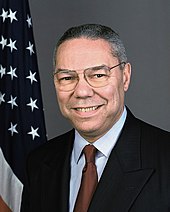

Former Secretary of State Colin Powell

Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice

- William Bennett,[a] Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy (1989–90); United States Secretary of Education (1985–99)[11]

- Bill Brock, United States Secretary of Labor (1985-87); United States Trade Representative (1981-85); U.S. Senator from Tennessee (1971-77); Chairman of the Republican National Committee (1977-81)[12]

- Michael Chertoff, United States Secretary of Homeland Security (2005–09); Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (2003–05) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[13][14]

- Bill Cohen, United States Secretary of Defense (1997–2001); United States Senator from Maine (1979–97) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[15][16]

- Robert Gates, United States Secretary of Defense (2006–11); Director of Central Intelligence (1991–93)[17]

- Carlos Gutierrez, United States Secretary of Commerce (2005–09) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[18]

- Carla Anderson Hills, United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (1975–77), United States Trade Representative (1989–93) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[13][18]

- Ray LaHood, United States Secretary of Transportation (2009–13), U.S. Representative from Illinois (1995–2009)[19]

- Greg Mankiw, Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers (2003–05)[20]

- Mel Martinez, United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (2001–03); United States Senator from Florida (2005–09); General Chair of the Republican National Committee (2007)[21][22]

- Michael Mukasey, United States Attorney General (2007–09)[23]

- John Negroponte, United States Ambassador to the United Nations (2001–04); Director of National Intelligence (2005–07); United States Deputy Secretary of State (2007–09) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[13][18]

- Henry Paulson, United States Secretary of the Treasury (2006–09) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[24]

- Colin Powell, United States Secretary of State (2001–05), National Security Advisor (1987–89) (voted for Hillary Clinton)[25]

- William K. Reilly, Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (1989–92) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[18]

- Condoleezza Rice,[b] United States Secretary of State (2005–09), National Security Advisor (2001–05)[26]

- Tom Ridge, United States Secretary of Homeland Security (2003–05); Homeland Security Advisor (2001–03); Governor of Pennsylvania (1995–2001)[13][27][28]

- William Ruckelshaus, Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970–73, 1983–85) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[18]

- George P. Shultz, United States Secretary of Labor (1969–70); Director of the Office of Management and Budget (1970–72); United States Secretary of the Treasury (1972–74); United States Secretary of State (1982–89)[20]

- Louis Wade Sullivan, United States Secretary of Health and Human Services (1989–93) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[29]

- Christine Todd Whitman, Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (2001–03); Governor of New Jersey (1994–2001) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[30]

- Robert Zoellick, United States Deputy Secretary of State (2005–06); U.S. Trade Representative (2001–05); President of the World Bank Group (2007–12)[13]

Governors[edit]

- Current

Ohio Governor John Kasich

- Charlie Baker, Massachusetts (2015–present)[31]

- Robert J. Bentley,[a] Alabama (2011–present)[32]

- Dennis Daugaard,[a][b] South Dakota (2011–present)[33]

- Bill Haslam, Tennessee (2011–present)[34]

- Gary Herbert,[a] Utah (2009–present)[35]

- Larry Hogan, Maryland (2015–present)[36][37]

- Susana Martinez, New Mexico (2011–present); Chair of the Republican Governors Association (2015–present)[38]

- Brian Sandoval,[a] Nevada (2011–present)[39]

- Rick Snyder, Michigan (2011–present)[40]

- Former

Former Massachusetts Governor and 2012 nominee for President Mitt Romney

- Arne Carlson, Minnesota (1991–99) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[18]

- A. Linwood Holton Jr., Virginia (1970–74); Assistant Secretary of State for Legislative Affairs (1974–75) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[41]

- Jon Huntsman Jr.,[a] Utah (2005–09); United States Ambassador to China (2009–11); United States Ambassador to Singapore (1992–93)[42]

- William Milliken, Michigan (1969–83) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[43]

- Kay A. Orr, Nebraska (1987–91)[44]

- Tim Pawlenty,[a] Minnesota (2003–11)[45]

- Marc Racicot, Montana (1993–01); Chair of the Republican National Committee (2001–03)[46]

- Mitt Romney, Massachusetts (2003–07), 2012 nominee for President[47]

- Arnold Schwarzenegger, California (2003–11)[48]

- William Weld, Massachusetts (1991–97) (2016 Libertarian nominee for Vice President)[49]

- Christine Todd Whitman, New Jersey (1994-2001) [50]

U.S. Senators[edit]

Arizona Senator and 2008 nominee for President John McCain

- Current

- Susan Collins, Maine (1997–present)[51](supported Mike Pence for Vice President; presidential vote unknown)[citation needed]

- Jeff Flake,[b] Arizona (2013–present)[52][53]

- Cory Gardner,[a][b] Colorado (2015–present) (writing-in Mike Pence)[54]

- Dean Heller, Nevada (2011–present)[55]

- Mike Lee,[b] Utah (2011–present)[56](voted for Evan McMullin)[57]

- John McCain,[a] Arizona (1987–present); 2008 nominee for President[58]

- Lisa Murkowski,[b] Alaska (2002–present)[59]

- Rob Portman,[a] Ohio (2010-present); United States Trade Representative (2005–06), Director of the Office of Management and Budget (2006–07) (writing-in Mike Pence)[60]

- Ben Sasse, Nebraska (2015–present)[21][61]

- Dan Sullivan,[a][b] Alaska (2015–present) (wrote in Mike Pence)[62]

- Former

- Kelly Ayotte,[c] New Hampshire (2011–17) (wrote in Mike Pence)[63]

- Mark Kirk,[a] Illinois (2010–17) (writing-in Colin Powell)[37]

- Norm Coleman, Minnesota (2003–09)[28][64]

- David Durenberger, Minnesota (1978–95) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[18]

- Slade Gorton, Washington (1981–87, 1989–2001) (endorsed Evan McMullin)[65]

- Gordon J. Humphrey, New Hampshire (1979–90) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[66][67]

- John Warner, Virginia (1979–2009); United States Secretary of the Navy (1972–74) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[68]

U.S. Representatives[edit]

Nevada U.S. Representative and 2016 nominee for U.S. Senate Joe Heck

- Sitting at the time of the Trump campaign

- Justin Amash, Michigan (2011–present)[28]

- Mike Coffman, Colorado (2009–present)[69]

- Barbara Comstock, Virginia (2015–present)[70]

- Carlos Curbelo, Florida (2015–present)[21][71]

- Rodney Davis,[a] Illinois (2013–present)[72]

- Charlie Dent, Pennsylvania (2005–present)[73]

- Bob Dold, Illinois (2011–13, 2015–17)[28][74]

- Jeff Fortenberry,[a] Nebraska (2005–present)[72]

- Scott Garrett,[a] New Jersey (2003–2017)[72]

- Kay Granger,[b] Texas (1997–present)[75]

- Richard L. Hanna, New York (2011–17) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[28][76]

- Cresent Hardy,[a] Nevada (2015–17)[77]

- Joe Heck,[a] Nevada (2011–17); 2016 nominee for U.S. Senate[77]

- Jaime Herrera Beutler, Washington (2011–present) (writing-in Paul Ryan)[78]

- Will Hurd, Texas (2015–present)[79]

- David Jolly, Florida (2014–17)[80]

- John Katko, New York (2015–present)[81]

- Adam Kinzinger, Illinois (2011–present)[82]

- Steve Knight, California (2015–present)[83]

- Frank LoBiondo,[a] New Jersey (1995–present) (writing-in Mike Pence)[84]

- Mia Love, Utah (2015–present)[85]

- Pat Meehan,[b] Pennsylvania (2011–present)[84]

- Erik Paulsen,[a] Minnesota (2009–present)[86]

- Reid Ribble, Wisconsin (2011–17)[28]

- Scott Rigell, Virginia (2011–17) (endorsed Gary Johnson)[21]

- Martha Roby,[b] Alabama (2011–present)[87][88]

- Tom Rooney,[a] Florida (2009–present)[72]

- Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, Florida (1989–present)[28]

- Mike Simpson,[a] Idaho (1999–present)[11]

- Fred Upton, Michigan (1987–present)[89]

- David Valadao, California (2013–present)[90]

- Ann Wagner,[a] Missouri (2013–present)[91]

Host of Morning Joe on MSNBC and former U.S. Representative from Florida Joe Scarborough

- Former

- Steve Bartlett, Texas (1983–91)[92]

- Bob Bauman, Maryland (1973–81)[92]

- Sherwood Boehlert, New York (1993–2007) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[93]

- Jack Buechner, Missouri (1987–91)[92]

- Tom Campbell, California (1989–93, 1995–2001) (endorsed Gary Johnson)[94]

- Bill Clinger, Pennsylvania (1979–97)[92]

- Tom Coleman, Missouri (1976–93)[92]

- Geoff Davis, Kentucky (2005–12)[92]

- Mickey Edwards, Oklahoma (1977–93)[92]

- Harris Fawell, Illinois (1985–99)[92]

- Ed Foreman, Texas (1963–65, 1969–71)[92]

- Amo Houghton, New York (1987–2005)[92]

- Bob Inglis, South Carolina (1993–99, 2005–11)[28]

- Jim Kolbe, Arizona (1985–2007) (endorsed Gary Johnson)[95]

- Steve Kuykendall, California (1999–2001)[92]

- Jim Leach, Iowa (1977–2007)[92]

- Pete McCloskey, California (1967–83)[92]

- Connie Morella, Maryland (1987–2003) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[18]

- Mike Parker, Mississippi (1989–99); Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works (2001–02)[92]

- Tom Petri, Wisconsin (1979–2015)[92]

- John Porter, Illinois (1980–2001)[92]

- Joe Scarborough, Florida (1995–2001); commentator and author[96]

- Claudine Schneider, Rhode Island (1981–91) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[93]

- Chris Shays, Connecticut (1987–2009) (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[18]

- Peter Smith, Vermont (1989–11)[92]

- Mark Souder, Indiana (1995–2010)[97]

- J.C. Watts, Oklahoma (1995–2003)[21]

- Edward Weber, Ohio (1981–83)[92]

- Vin Weber, Minnesota (1983–93)[98]

- G. William Whitehurst, Virginia (1969–87)[92]

- Dick Zimmer, New Jersey (1991–97) (endorsed Gary Johnson)[99]

Former State Department officials[edit]

- Richard Armitage, Deputy Secretary of State; Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[100]

- John B. Bellinger III, Legal Adviser of the Department of State; Legal Adviser to the National Security Council[13]

- Robert Blackwill, United States Ambassador to India; Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Planning (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[13][18]

- R. Nicholas Burns, Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs; United States Ambassador to NATO; United States Ambassador to Greece (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[101]

- Eliot A. Cohen, Counselor of the United States Department of State[13][21]

- Chester Crocker, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs[23]

- Jendayi Frazer, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs[13]

- James K. Glassman, Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[23]

- David F. Gordon, Director of Policy Planning[13]

- Donald Gregg, United States Ambassador to South Korea[20]

- David A. Gross, U.S. Coordinator for International Communications and Information Policy (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[18]

- John Hillen, Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs[13]

- Reuben Jeffery III, Under Secretary of State for Economic Growth, Energy, and the Environment[13]

- Robert Joseph, Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Affairs[23]

- David J. Kramer, Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor[13]

- Stephen D. Krasner, Director of Policy Planning[23]

- Frank Lavin, United States Ambassador to Singapore; Under Secretary of Commerce for International Trade (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[18]

- Robert McCallum, United States Ambassador to Australia; Acting United States Deputy Attorney General[13]

- Richard Miles, United States Ambassador to Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, and Georgia; Acting United States Ambassador to Kyrgyzstan[23]

- Roger Noriega, Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs[23]

- John Osborn, Member of the U.S. Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy[23]

- Kristen Silverberg, Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs[13]

- William Howard Taft IV, Legal Adviser of the Department of State; United States Ambassador to NATO; United States Deputy Secretary of Defense[13]

- Shirin R. Tahir-Kheli, Senior Advisor for Women’s Empowerment; Special Assistant to the President for Democracy, Human Rights and International Operations (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[13][18]

- Betty Tamposi, Assistant Secretary of State for Consular Affairs (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[102]

- Peter Teeley, United States Ambassador to Canada (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[18]

- Robert Tuttle, United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom (endorsed Hillary Clinton)[103]

- Philip Zelikow, Counselor of the United States Department of State[13]

Former Defense Department officials[edit]

- Don Bacon,[b] Brigadier General, United States Air Force; Representative for Nebraska’s 2nd district[104]

- Seth Cropsey, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations/Low Intensity Conflict & Interdependent Capabilities[23]