|

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Headquarters | Vienna, Austria | |||

| Official language | English | |||

| Type | Cartel | |||

| Membership | ||||

| Leaders | ||||

| • | Secretary General | Abdallah Salem el-Badri | ||

| Establishment | Baghdad, Iraq | |||

| • | Statute | 10–14 September 1960 | ||

| • | in effect | January 1961 | ||

| Area | ||||

| • | Total | 13,759,546 km2 5,312,590 sq mi |

||

| Population | ||||

| • | estimate | 669,521,706 | ||

| • | Density | 48.7/km2 126.1/sq mi |

||

| Currency | Indexed as USD-per-barrel | |||

| Website www.OPEC.org |

||||

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, /ˈoʊpɛk/ oh-pek), is an international organization headquartered in Vienna, Austria. OPEC was established in Baghdad, Iraq on 10–14 September 1960.[1] The formation of OPEC represented a collective act of sovereignty by petroleum-exporting nations, and marked a turning point in state control over natural resources. OPEC was formed when the international oil market was largely dominated by a group of multinational companies known as the “Seven Sisters“. In the 1960s OPEC ensured that oil companies could not unilaterally cut prices.[2]:503–505

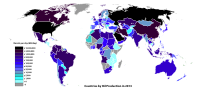

OPEC’s mission is “to coordinate and unify the petroleum policies of its member countries and ensure the stabilization of oil markets, in order to secure an efficient, economic and regular supply of petroleum to consumers, a steady income to producers, and a fair return on capital for those investing in the petroleum industry.”[3] As of December 2015, OPEC has thirteen members:Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia (the de facto leader), the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela.[4] As of 2014, approximately 80% of the world’s proven oil reserves were located in OPEC member countries, and two-thirds of OPEC’s reserves were located in the Middle East.[5]

According to the United States Energy Information Administration (EIA), OPEC crude oil production is an important factor affecting global oil prices. OPEC sets production targets for its member nations and generally, when OPEC production targets are reduced, oil prices increase. Projections of changes in Saudi production result in changes in the price of benchmark crude oils.[6]Within their sovereign territories, the national governments of OPEC members are able to impose production limits on both government-owned and private oil companies.[7] In December 2014, “OPEC and the oil men” ranked as number 3 on Lloyd’s list of “the top 100 most influential people in the shipping industry”.

Membership[edit]

Current members[edit]

As of December 2015, OPEC has 13 member countries: six in the Middle East (Western Asia), one in Southeast Asia, four in Africa, two in South America. Their combined rate of oil production represents approximately 40% of the world’s total:

| Country | Region | Joined OPEC[9] | Population (July 2012)[10] |

Area (km²)[11] |

Production (bbl/day, 2014)[12] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 1969 | 37,367,226 | 2,381,740 | 1,721,000 (17th) | |

| Africa | 2007 | 18,056,072 | 1,246,700 | 1,756,000 (16th) | |

| South America | (1973) 2007[A 1] | 15,223,680 | 283,560 | 557,000 (28th) | |

| Southeast Asia | (1962) 2015[A 2] | 248,645,008 | 1,904,569 | 911,000 (22nd) | |

| Middle East | 1960[A 3] | 78,868,711 | 1,648,000 | 3,375,000 (7th) | |

| Middle East | 1960[A 3] | 31,129,225 | 437,072 | 3,371,000 (8th) | |

| Middle East | 1960[A 3] | 2,646,314 | 17,820 | 2,780,000 (11th) | |

| Africa | 1962 | 5,613,380 | 1,759,540 | 516,000 (29th) | |

| Africa | 1971 | 170,123,740 | 923,768 | 2,427,000 (13th) | |

| Middle East | 1961 | 1,951,591 | 11,437 | 2,055,000 (14th) | |

| Middle East | 1960[A 3] | 26,534,504 | 2,149,690 | 11,624,000 (2nd) | |

| Middle East | 1967 | 5,314,317 | 83,600 | 3,471,000 (6th) | |

| South America | 1960[A 3] | 28,047,938 | 912,050 | 2,689,000 (12th) | |

| Total | 669,521,706 | 13,759,546 | 37,253,000 | ||

In October 2015, Sudan formally submitted an application to join OPEC.[13] Approval of a new member country requires agreement by three-fourths of the existing members, including all five of the founders.[14]

Former members[edit]

| Country | Region | Joined OPEC | Left OPEC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 1975 | 1994 |

Some commentators consider that the United States was a de facto member during its formal occupation of Iraq due to its leadership of the Coalition Provisional Authority.[15][16] But this is not borne out by the minutes of OPEC meetings, as no US representative attended in an official capacity.[17][18]

Leadership and decision-making[edit]

The OPEC Conference is the supreme authority of the Organization, and consists of delegations normally headed by the oil ministers of member countries. The Conference usually meets at the Vienna headquarters, at least twice a year and in additional extraordinary sessions whenever required. It operates on the principle of unanimity, and one member, one vote.[14] However, since Saudi Arabia is by far the largest oil exporter in the world, it serves as “OPEC’s de facto leader”.[19] The chief executive of the Organization is the OPEC Secretary General.

Publications and research[edit]

Since 2007, OPEC publishes the World Oil Outlook (WOO) annually, in which it presents a comprehensive analysis of the global oil industry including medium- and long-term projections for supply and demand.[20]

Crude oil benchmarks[edit]

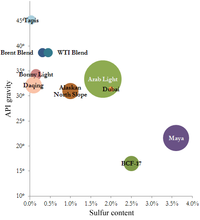

A “crude oil benchmark” is a standardized petroleum product that serves as a convenient reference price for buyers and sellers of crude oil. Benchmarks are used because oil prices differ based on variety, grade, delivery date and location.

The OPEC Reference Basket of Crudes is an important benchmark for crude oil prices. It is currently calculated as a weighted average of prices for petroleum blends from OPEC member countries: Saharan Blend (Algeria), Girassol (Angola), Oriente (Ecuador), Iran Heavy (Islamic Republic of Iran), Basra Light (Iraq), Kuwait Export (Kuwait), Es Sider (Libya), Bonny Light (Nigeria), Qatar Marine (Qatar), Arab Light (Saudi Arabia), Murban (UAE), and Merey (Venezuela).[21]

North Sea Brent Crude Oil is the leading benchmark for Atlantic basin crude oils, and is used to price approximately two-thirds of the world’s traded crude oil.[22] Other well-known benchmarks are West Texas Intermediate (WTI), Dubai Crude, Oman Crude, and Urals oil.

Spare capacity[edit]

The U.S. Energy Information Administration, the statistical arm of the U.S. Department of Energy, defines spare capacity for crude oil market management, “as the volume of production that can be brought on within 30 days and sustained for at least 90 days.” OPEC spare capacity “provides an indicator of the world oil market’s ability to respond to potential crises that reduce oil supplies.”[6]

In November 2014, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated that OPEC’s effective spare capacity was 3.5 million barrels per day (560,000 m3/d) and that this number would increase to a peak in 2017 of 4.6 million barrels per day (730,000 m3/d).[23] By November 2015, the IEA changed its assessment “with OPEC’s spare production buffer stretched thin, as Saudi Arabia – which holds the lion’s share of excess capacity – and its Gulf neighbours pump at near-record rates.”[24]

History[edit]

In 1949 Venezuela and Iran were the first countries to move towards the establishment of OPEC by approaching Iraq, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, suggesting that they exchange views and explore avenues for regular and closer communication among petroleum-producing nations.[25]

In 1959, the International Oil Companies (IOCs) reduced the posted price for Venezuelan crude by 5¢ and then 25¢ per barrel, and that for Middle Eastern crude by 18¢ per barrel.[25]

The First Arab Petroleum Congress convened in Cairo, Egypt, where they established an ‘Oil Consultation Commission’ to which IOCs should present price change plans to authorities of producing countries.[25] In 1959 journalist Wanda Jablonski introduced Abdullah Tariki to Juan Pablo Perez Alfonzo at the Arab Oil Congress in Cairo. They were both infuriated by the cut in posted prices by IOCs or Multinational Oil Companies (MOCs). This meeting resulted in the Maadi Pact or Gentlemen’s Agreement.[2]:499

In 1960, journalist Wanda Jablonski reported a marked hostility toward the West and a growing outcry against absentee landlordism in the Middle East. In his influential book entitled The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power, Daniel Yergin described how the Standard Oil, who controlled 75% of the US oil business, in August 1960 with no direct warning to oil exporters, announced cut of up 7 per cent of the posted prices of Middle Eastern crude oils. Esso and other oil companies unilaterally reduced the posted price for Middle East crudes.[26] Middle Eastern countries already felt resentment towards the West over the absentee landlordism of MOCs who at the time controlled all oil operations within the host countries.[2]:503

Founding[edit]

In 10–14 September 1960, the Baghdad conference was held at the initiative of the Venezuelan Mines and Hydrocarbons minister Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso and the Saudi Arabian Energy and Mines minister Abdullah al-Tariki. The governments of Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela met in Baghdad to discuss ways to increase the price of the crude oil produced by their respective countries and respond to unilateral actions by the MOCs who at the time controlled all oil operations within the host countries. “Together with Arab and non-Arab producers, Saudi Arabia formed the Organization of Petroleum Export Countries (OPEC) to secure the best price available from the major oil corporations.”[27]

Iraq, Kuwait, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela were the OPEC founding member nations in 1960. Later it was joined by nine more governments: Libya (1962), United Arab Emirates (1967), Qatar (1961), Indonesia (1962–2009, rejoined 2015), Algeria (1969), Nigeria (1971), Ecuador (1973–1992, rejoined 2007), Angola (2007), and Gabon(1975–1994). The Arab countries originally called for OPEC headquarters to be in Bagdad or Beirut, but Venezuela argued for a neutral location, and so Geneva, Switzerlandwas chosen. However, on 1 September 1965, OPEC moved to Vienna, Austria.[28]

OPEC was founded to unify and coordinate members’ petroleum policies. Between 1960 and 1975, the organization expanded to include Qatar , Indonesia, Libya, the United Arab Emirates, Algeria, and Nigeria. Ecuador and Gabon were early members of OPEC, but Ecuador withdrew on 31 December 1992[29] because it was unwilling or unable to pay a $2 million membership fee and felt that it needed to produce more oil than it was allowed to under the OPEC quota,[30] although it rejoined in October 2007. Similar concerns prompted Gabon to suspend membership in January 1995.[31] Angola joined on the first day of 2007. Norway and Russia have attended OPEC meetings as observers. Indicating that OPEC is not averse to further expansion, Mohammed Barkindo, OPEC’s Secretary General, asked Sudan to join.[32] Iraq remains a member of OPEC, but Iraqi production has not been a part of any OPEC quota agreements since March 1998.

In the 1970s, OPEC began to gain influence and steeply raised oil prices during the 1973 oil crisis in response to US aid to Israel during the Yom Kippur War.[33] It lasted until March 1974.[34] OPEC added to its goals the selling of oil for socio-economic growth of the poorer member nations, and membership grew to 13 by 1975.[28] A few member countries became centrally planned economies.[28]

In a 1979 U.S. District Court decision held that OPEC’s pricing decisions have sovereign immunity as “governmental” acts of state, as opposed to “commercial” acts, and are therefore beyond the legal reach of U.S. courts competition law and are protected by the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976.[35][36]

In the 1980s, the price of oil was allowed to rise before the adverse effects of higher prices caused demand and price to fall. The OPEC nations, which depended on revenue from oil sales, experienced severe economic hardship from the lower demand for oil and consequently cut production in order to boost the price of oil. During this time, environmental issues began to emerge on the international energy agenda.[28] Lower demand for oil saw the price of oil fall back to 1986 levels by 1998–99.

In the 2000s, a combination of factors pushed up oil prices even as supply remained high. Prices rose to then record-high levels in mid-2008 before falling in response to the2007 financial crisis. OPEC’s summits in Caracas and Riyadh in 2000 and 2007 had guiding themes of stable energy markets, sustainable oil production, and environmental sustainability.[28]

In April 2001, OPEC, in collaboration with five other international organisations (APEC, Eurostat, IAE, OLADE and the UNSD) launched the Joint Oil Data Exercise, which became rapidely the Joint Organization Data Initiative (JODI).

In 2003 the International Energy Agency (IEA) and OPEC held their first joint workshop on energy issues and they continued to meet since then to better “understand trends, analysis and viewpoints and advance market transparency and predictability.”[37]:7

By 2011 OPEC called for more efforts by governments and regulatory bodies to curb excessive speculation in oil futures markets. OPEC claimed this increased volatility in oil prices, disconnected price from market fundamentals. In 2011 Nymex oil future trades reached record highs. By mid-March the Nymex WTI “exceeded 1.5 million futures contracts, 18 times higher than the volume of daily traded physical crude.”[38]

While there have been some allegations that OPEC acted as a cartel when it adopted output rationing in order to maintain price in 1996, for example,[39] Jeff Colgan argued in 2013 that, since 1982, countries cheated on their quotas 96% of the time, largely neutralizing the ability of OPEC to collectively influence prices.[40]

In 2011 the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated that OPEC would break above the US$1 trillion mark earnings for the first time at US$1.034 trillion. In 2008 OPEC earned US$965 billion.[41]

1973 oil embargo[edit]

In October 1973, OPEC declared an oil embargo in response to the United States’ and Western Europe’s support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973. The result was a rise in oil prices from $3 per barrel to $12 starting on 17 October 1973, and ending on 18 March 1974 and the commencement of gas rationing. Other factors in the rise in gasoline prices included a market and consumer panic reaction, the peak of oil production in the United States around 1970 and the devaluation of the U.S. dollar.[42] U.S. gas stations put a limit on the amount of gasoline that could be dispensed, closed on Sundays, and limited the days gasoline could be purchased based on license plates. Even after the embargo concluded, prices continued to rise.

The Oil Embargo of 1973 had a lasting effect on the United States. The Federal government got involved first with President Richard Nixon recommending citizens reduce their speed for the sake of conservation, and later Congress issuing a 55 mph limit at the end of 1973. Daylight saving time was extended year round to reduce electrical use in the American home. Smaller, more fuel efficient cars were manufactured.

On 4 December 1973, Nixon also formed the Federal Energy Office as a cabinet office with control over fuel allocation, rationing, and prices.[43] People were asked to decrease their thermostats to 65 degrees and factories changed their main energy supply to coal.

One of the most lasting effects of the 1973 oil embargo was a global economic recession. Unemployment rose to the highest percentage on record while inflation also spiked. Consumer interest in large gas guzzling vehicles fell and production dropped. Although the embargo only lasted a year, during that time oil prices had quadrupled and OPEC nations discovered that their oil could be used as both a political and economic weapon against other nations.[44][45]

OPEC aid[edit]

OPEC aid dates from well before the 1973–1974 oil price explosion. Kuwait has operated a program since 1961 (through the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development).

The OPEC Special Fund “was conceived […] in Algiers, Algeria, in March 1975”, and formally founded early the following year. “A Solemn Declaration ‘reaffirmed the natural solidarity which unites OPEC countries with other developing countries in their struggle to overcome underdevelopment,’ and called for measures to strengthen cooperation between these countries”, operating under a reasoning that the Fund’s “resources are additional to those already made available by OPEC states through a number of bilateral and multilateral channels.” The Fund became a fully fledged permanent international development agency in May 1980 and was renamed the OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID), the designation it currently holds.[46][47]

1975 hostage incident[edit]

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2011) |

On 21 December 1975, Ahmed Zaki Yamani and the other oil ministers of the members of OPEC were taken hostage in Vienna, Austria, where the ministers were attending a meeting at the OPEC headquarters. The hostage attack was orchestrated by a six-person team led by Venezuelan terrorist Carlos the Jackal (which included Gabriele Kröcher-Tiedemann and Hans-Joachim Klein). The self-named “Arm of the Arab Revolution” group called for the liberation of Palestine. Carlos planned to take over the conference by force and kidnap all eleven oil ministers in attendance and hold them for ransom, with the exception of Ahmed Zaki Yamani and Iran’s Jamshid Amuzegar, who were to be executed.

The terrorists searched for Ahmed Zaki Yamani and then divided the sixty-three hostages into groups. Delegates of friendly countries were moved toward the door, ‘neutrals’ were placed in the centre of the room and the ‘enemies’ were placed along the back wall, next to a stack of explosives. This last group included those from Saudi Arabia, Iran, Qatar and the UAE.

Carlos arranged bus and plane travel for the team and 42 hostages, with stops in Algiers and Tripoli, with the plan to eventually fly to Aden then Baghdad, where Yamani and Amuzegar would be killed. All 30 non-Arab hostages were released in Algiers, excluding Amuzegar. Additional hostages were released at another stop. With only 10 hostages remaining, Carlos held a phone conversation with Algerian President Houari Boumédienne who informed Carlos that the oil ministers’ deaths would result in an attack on the plane. Boumédienne must also have offered Carlos asylum at this time and possibly financial compensation for failing to complete his assignment. Carlos expressed his regret at not being able to murder Yamani and Amuzegar, then he and his comrades left the plane. Hostages and Carlos and his team walked away from the situation.

Some time after the attack it was revealed by Carlos’ accomplices that the operation was commanded by Wadi Haddad, a Palestinian terrorist and founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. It was also claimed that the idea and funding came from an Arab president, widely thought to be Muammar al-Gaddafi. In the years following the OPEC raid, Bassam Abu Sharif and Klein claimed that Carlos had received a large sum of money in exchange for the safe release of the Arab hostages and had kept it for his personal use. There is still some uncertainty regarding the amount that changed hands but it is believed to be between US$20 million and US$50 million. The source of the money is also uncertain, but, according to Klein, it was from “an Arab president.” Carlos later told his lawyers that the money was paid by the Saudis on behalf of the Iranians and was, “diverted en route and lost by the Revolution”.[48]

1980s oil glut[edit]

OPEC net oil export revenues for 1972–2007[49]

In response to the high oil prices of the 1970s, industrial nations took steps to reduce dependence on oil. Utilities switched to usingcoal, natural gas, or nuclear power while national governments initiated multibillion-dollar research programs to develop alternatives to oil. Demand for oil dropped by five million barrels a day while oil production outside of OPEC rose by fourteen million barrels daily by 1986. During this time, the percentage of oil produced by OPEC fell from 50% to 29%. The result was a six-year price decline that culminated with a 46 percent price drop in 1986.

In order to combat falling revenues, Saudi Arabia pushed for production quotas to limit production and boost prices. When other OPEC nations failed to comply, Saudi Arabia slashed production from 10 million barrels daily in 1980 to just one-quarter of that level in 1985. When this proved ineffective, Saudi Arabia reversed course and flooded the market with cheap oil, causing prices to fall to under ten dollars a barrel. The result was that high price production zones in areas such as the North Sea became too expensive. Countries in OPEC that had previously failed to comply to quotas began to limit production in order to shore up prices.[50]

Responding to war and low prices[edit]

Leading up to the 1990–91 Gulf War, The President of Iraq Saddam Hussein recommended that OPEC should push world oil prices up, helping all OPEC members financially. But the division of OPEC countries occasioned by the Iraq-Iran War and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait marked a low point in the cohesion of OPEC. Once supply disruption fears that accompanied these conflicts dissipated, oil prices began to slide dramatically.

After oil prices slumped at around $15 a barrel in the late 1990s, joint diplomacy achieved a slowing down of oil production beginning in 1998.

In 2000, Venezuela President Hugo Chávez hosted the first summit of OPEC in 25 years in Caracas. The next year, however, the September 11, 2001 attacks against the United States, and the following invasion of Afghanistan, and 2003 invasion of Iraq and subsequent occupation prompted a sharp rise in oil prices to levels far higher than those targeted by OPEC itself during the previous period. Price volatility peaked in 2008, as crude oil surged to a record US$147/b in July and then plunged to just US$32/b in December, during the worst global recession since World War II.[51]

In May 2008, Indonesia announced that it would leave OPEC when its membership expired at the end of that year, having become a net importer of oil and being unable to meet its production quota.[52] A statement released by OPEC on 10 September 2008 confirmed Indonesia’s withdrawal, noting that it “regretfully accepted the wish of Indonesia to suspend its full Membership in the Organization and recorded its hope that the Country would be in a position to rejoin the Organization in the not too distant future.”[53]Indonesia is still exporting light, sweet crude oil and importing heavier, more sour crude oil to take advantage of price differentials (import is greater than export).

Production disputes[edit]

The economic needs of the OPEC member states often affects the internal politics behind OPEC production quotas. Various members have pushed for reductions in production quotas to increase the price of oil and thus their own revenues.[54] These demands conflict with Saudi Arabia’s stated long-term strategy of being a partner with the world’s economic powers to ensure a steady flow of oil that would support economic expansion.[55] Part of the basis for this policy is the Saudi concern that expensive oil or supply uncertainty will drive developed nations to conserve and develop alternative fuels. To this point, former Saudi Oil Minister Sheikh Yamani famously said in 1973: “The stone age didn’t end because we ran out of stones.”[56][57]

On 10 September 2008, one such production dispute occurred when the Saudis reportedly walked out of OPEC negotiating session where the organization voted to reduce production. Although Saudi Arabian OPEC delegates officially endorsed the new quotas, they stated anonymously that they would not observe them. The New York Timesquoted one such anonymous OPEC delegate as saying “Saudi Arabia will meet the market’s demand. We will see what the market requires and we will not leave a customer without oil. The policy has not changed.”[58]

With regard to disputes related to international trade, OPEC has not been involved in any related to the rules of the World Trade Organization, even though the objectives, actions, and principles of the two organizations diverge considerably.[59]

Oil price decline 2014–2015[edit]

According to the New York Times the oil-drilling boom in the United States has increased oil production by over 70 percent since 2008 and has reduced the United States oil imports from OPEC by fifty per cent.[60] United States oil inventory has increased because of this new production and surplus oil.[61] The price of oil has been influenced by market participants shorting crude oil in the United States which cannot be exported.[62] The low price of oil has created record profits for oil refineries.[63]

Since 2011 the United States absorbed the rapidly increased domestic production of sweet, light, tight oil by reducing like-for-like or similar grade, imported crude oil[64] from Nigerian and other African suppliers.[60] From 2011 to 2013 fifty per cent of oil import reductions impacted light crude (API gravity35+).[65] Almost 96 per cent of the 1.8 million barrels per day (290,000 m3/d) of its growth comes from light, sweet crude from tight resource formations.[64] As domestic production continues to increase, the U.S. is facing future challenges of absorbing the light, sweet tight oil.[65]

In June 2014 crude oil prices abruptly dropped by about a third as U.S. shale oil production increased and China and Europe’s demand for oil decreased. Just before the United States rapidly backed out of the crude oil import market because of booming national production, the spot price of North Sea Brent crude oil peaked on 17 June 2014 at more than US$115 per barrel.[66]

Nigeria is the largest producer of sweet oil in OPEC. By July 2014, as the US stopped importing light sweet crude, more crude oil became available to refineries in China, India, Japan and South Korea. They collectively purchased 42% more Nigerian crude in 2014 compared with 2013. Starting in June 2014 Saudi Aramco—Saudi Arabia’s national oil and gas company and the world’s largest oil company in terms of production—discounted the price of its crude to Asian refineries[67] to compete with oil from Nigerian and other African suppliers.[60]

In their press release 27 November 2014 at the OPEC Conference in Vienna, it was announced that the ‘OECD-Americas’ was the main non-OPEC oil supply contributor to an anticipated supply growth of 1.4 million barrels per day (220,000 m3/d) to average 57.3 million barrels per day (9,110,000 m3/d) in 2015. From 2011 until mid-June 2014 the annual average price of oil was about US$110 per barrel. Since June 2014 however, the price of oil slid to US$80. OPEC argued that this drop in the price of oil was not exclusively “attributed to oil market fundamentals.” While oil market fundamentals, “ample supply, moderate demand, a stronger US dollar and uncertainties about global economic growth” contributed to the drop in price, “speculative activity in the oil market has also been an important factor.”[68]

In spite of global oversupply, on 27 November 2014 in Vienna, Saudi Oil Minister Ali al-Naimi, blocked the appeals from the poorer OPEC member states, such as Venezuela, Iran and Algeria, for production cuts. Benchmark crude, Brent oil plunged to US$71.25, a four-year low. Al-Naimi argued that the market would be left to correct itself. OPEC had a “long-standing policy of defending prices.” According to some analysts, OPEC would let price of Brent oil drop to US$60 to slow down US shale oil production.[69] In spite of a troubled economy in member countries, al-Naimi repeated his statement on Saudi inaction.[70]

By November 2014 with production at 30.56 million barrels per day (4,859,000 m3/d) OPEC entered its sixth month of exceeding their collective target production.[66] By 11 December 2014 the price of OPEC Reference Basket of Crudes had dropped to US$60.50[71] and by 13 December the price of Brent ICE dropped to US$61.85.[66] On 12 January 2015 price of OPEC Reference Basket of Crudes had dropped to US$43.55[71] In February 2015, OPEC had entered its ninth consecutive month of exceeding its collective target production.[72]

In August 2015, Venezuela President Nicolas Maduro sought an emergency OPEC meeting and joint coordination with Russia to stem the tumble in oil prices.[73] Ecuador supported Venezuela’s position.[74] Previously in February 2015, Nigeria sought to call an emergency OPEC meeting if oil prices continued to decline.[75] In April 2015, Iran and Libya called on OPEC to reduce oil output.[76] Angola and Algeria also sought a production cut in cooperation with the African Petroleum Producers Association.[77] Algeria said Mexico supported the bid to cut oil output.[78] In September 2015, President Vladimir Putin met Venezuelan President Nicolas to discuss oil policies.[79] Saudi Arabia, though, pushed OPEC to increase production levels.[80]

In mid-2015, Bank of America said that OPEC is “effectively dissolved”,[81][82] and JPMorgan Chase estimated that OPEC’s decision to maintain production was costing Saudi Arabia about $90 billion/year and probably close to $200 billion/year for OPEC as a whole.[83]

In October 2015, OPEC held an unusual meeting with oil officials from nonmember states like Russia and Mexico, in a bid to forge a common response to fallen oil prices.[84] At OPEC’s Vienna meeting on 4 December 2015, after exceeding its production ceiling for 18 consecutive months, and with Indonesia rejoining and Iranian output poised to surge with the removal of international sanctions, OPEC decided to set aside its ineffective production ceiling until the next ministerial conference in June 2016.[85][86][87] On 9 December 2015, the OPEC Reference Basket was down to US$34.80 for the first time since December 2008