Category Archives: NAU

Laws, Part 1 (by Plato) Philosophy Audiobook

3 ways Justin Trudeau has wasted taxpayer dollars jetting around the world!

Justin Trudeau’s Apologies

CANADA: Imam compares Justin Trudeau to Islamic hero for honoring Muslims and removing suspicion that terrorism has anything to do with Islam

He also compared Trudeau to Turkish President Recep Erdogan who is turning Turkey into an Islamic fundamentalist state.

h/t Vlad Tepesblog

Lot of photos of Trudeau praying at mosques and kissing up to Muslims. Makes one wonder if he hasn’t already secretly converted to Islam.

In Justin Trudeau’s ‘Canadastan,’ you get arrested for speaking out against Muslim terrorist attacks in Paris

TORONTO: Free speech activist Eric Brazau was arrested for publicly expressing his outrage at the bloodbath in Paris by Muslim terrorists. Looks like the newly-elected government of Justin Trudeau wasted no time in accommodating the powerful Muslim lobby that helped him come to power.

Blogwrath The events shown in the video took place on November 13, 2015. After hearing about the Muslim terrorist attacks in Paris, the free speech activist Eric Brazau decided to express his frustration by speaking with people on the street. However, any criticism of Islam is taboo among the Muslims and leftists who dominate downtown Toronto. Though he didn’t say anything hateful, Brazau was physically assaulted and verbally attacked. In the end his attackers called the police and he was taken away in handcuffs.

Eric Brazau, no stranger to controversy, is a Canadian political prisoner who spent nearly two years in jail for ridiculing and criticizing Islam in flyers and street shows (he is a licensed street art performer).

Just like in Germany, a crackdown on those who dare criticize Islam is underway. On the day of the Paris attacks Trudeau’s government threw out the appeal against allowing Muslim supremacists to mock the citizenship ceremony by appearing in face-covering headbags.

Trudeau Pledge Tracker: Cabinet is Fifty Percent Women

Turkish general election, November 2015

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

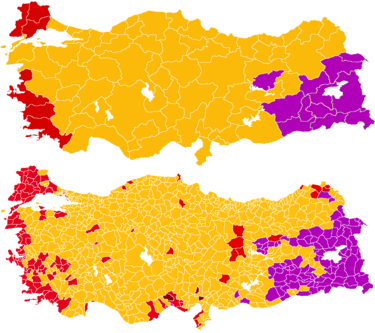

| Winners according to provinces:[1] AKP CHP MHP HDP |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the Turkish general election, November 2015 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunday, 1 November 2015Opinion polling · Electoral districts · Electoral system ·Controversies · Members elected | ||||

| Solution process · 2015 Suruç bombing · Turkey–ISIL conflict · 2015 PKK rebellion · Operation Martyr Yalçın ·Counter-terrorism raids · Syrian refugee crisis · Media censorship · Presidential system · Ankara bombings ·Government–Gülen conflict | ||||

|

Results

|

||||

|

Party

|

Votes

|

%

|

MPs

|

|

| AKP | 23,673,541 | 49.49% | 317 | |

| CHP | 12,109,985 | 25.31% | 134 | |

| HDP | 5,145,688 | 10.76% | 59 | |

| MHP | 5,691,737 | 11.90% | 40 | |

| Others | 2.54% | 0 | ||

|

Total

|

100.00% | 550 | ||

| ← June 2015 election | 2019 election→ | |||

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Turkey |

The Turkish general election of November 2015 was held on 1 November 2015 throughout the 85 electoral districts of Turkey to elect 550 members to the Grand National Assembly. It was the 25th general election in the History of the Republic of Turkey and elected the country’s 26th Parliament. The election resulted in theJustice and Development Party (AKP) regaining a Parliamentary majority following a ‘shock’ victory, having lost it five months earlier in the June 2015 general election.[2][3][4]

The snap election was called by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan on 24 August 2015 after the June election resulted in a hung parliament and coalition negotiations broke down. Although the election, dubbed as a ‘re-run’ of the inconclusive June election by President Erdoğan, was the 7th early election in the history of Turkish politics, it was the first to be overseen by an interim election government. The election rendered the 25th Parliament of Turkey, elected in June, the shortest in the Grand National Assembly’s history, lasting for just five months and being in session for a total of 33 hours.[5]

The election took place amid security concerns after ceasefire negotiations between the government andKurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) rebels collapsed in July, causing a resumption in separatist conflict in the predominately Kurdish south-east of the country. Close to 150 security personnel lost their lives in the ensuing conflict, causing tensions between Turkish and Kurdish nationalists and raising security concerns over whether an election could have been peacefully conducted in the south-east, where conditions were described as a ‘worsening bloodshed’ by observers.[6][7][8] Critics accused the government of deliberately sparking the conflict in order to win back votes it had lost to the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and decrease the turnout inPeoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) strongholds.[9][10][11][12][13] The election was preceded by the deadliest terrorist attack in Turkey’s modern history, after two suicide bombers killed 102 people attending a peace rally in central Ankara.[14] Numerous political parties, notably the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), ended up either entirely cancelling or significantly toning down their election campaigns following the attack.Fehmi Demir, the leader of the Rights and Freedoms Party (HAK-PAR), was killed in a traffic accident six days before the election.[15]

Amid speculation that the election would likely result in a second hung parliament, pollsters and commentators were found to have drastically underestimated the AKP vote, which bore resemblence to their record 2011 election victory.[16][17] With 49.5% of the vote and 317 seats, the party won a comfortable majority of 84, while the CHP retained its main opposition status with 134 seats and 25.4% of the vote. The results were widely seen as a ‘shock’ win for the AKP and was hailed as a massive personal victory for President Erdoğan.[18][19] The MHP and the HDP both saw decreases in support, with both hovering dangerously close to the 10% election threshold needed to win seats. The MHP, which was seen to have been punished for its perceivably unconstructive stance since June, halved their parliamentary representation from 80 to 40 and won 11.9% of the vote, while the HDP came third in terms of seats with 59 MPs despite coming fourth in terms of votes with 10.7%.

Background[edit]

Turkish politics is largely dominated by four main parties. The largest is the right-wing Islamist rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP), which has been described as a conservative democratic party and has been in power since winning a landslide victory in the 2002 general election. The main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) has remained as the second largest party since 2002, observing a centre-left social democratic and Kemalist ideology. The Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) observes aTurkish nationalist ideology and has maintained third party status in Parliament since the 2007 general election. The Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) was founded in 2012 and originates from the left-wing Peoples’ Democratic Congress. It is largely seen as a pro-Kurdish party and maintains an ideology of minority rights and anti-capitalism. All four parties surpassed the 10% election threshold in the June 2015 general election and won representation in Parliament, with no party winning a majority to govern alone. Smaller parties include the Islamist Felicity Party (SP), the left-wing nationalist Patriotic Party (VP), the centrist Independent Turkey Party (BTP) and the social democratic Democratic Left Party (DSP), though neither party managed to command a significant amount of support in previous elections.

June 2015 election[edit]

Elections were held on 7 June 2015 in order to elect the 25th Parliament of Turkey, following the expiry of the 24th Parliament’sfour-year term. Suffering a 9% decrease in their vote share, the governing AKP won 258 out of the 550 seats, 18 seats short of a majority. The CHP also suffered a slight decrease in their vote and seat share, winning 132 seats. The MHP and the HDP both won 80 seats, with the HDP managing to surpass the 10% election threshold despite concerns that it could fall below the boundary. The election resulted in the first hung parliament since the 1999 general election. The election result immediately raised speculation over an early general election.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan invited AKP leader Ahmet Davutoğlu to form a government on 9 July 2015, by virtue of leading the largest party in Parliament.[20] If a government was not formed within 45 days (until 23 August 2015), then Erdoğan reserved the right to either extend the 45-day period or call an early election.

Coalition negotiations[edit]

Coalition negotiations taking place between the AKP and CHP following theJune 2015 general election.

After being asked to form a government by virtue of leading the largest party in Parliament, AKP leader Ahmet Davutoğlu held talks with the leaders of the three opposition parties. With the HDP refusing to join a coalition with the AKP and the MHP preferring to remain in opposition, Davutoğlu entered extended negotiations with the main opposition CHP over a possible grand coalition deal. After 35 hours of negotiations spanning over 10 days, negotiations broke down after CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu claimed that Davutoğlu had only offered the CHP a role in a three-month government followed by early elections.[21] The CHP had previously made it a condition that any coalition deal should last for four years, the entire duration of the parliamentary term.[22]

Stating that early elections were the most likely possibility, Davutoğlu requested a meeting with MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli in a last-ditch attempt to form an AKP-MHP coalition. Bahçeli had previously announced his support for an early election, but later put forward four non-negotiable conditions for a possible coalition after a breakout of violence in the predominantly Kurdish south-eastern region of Turkey.[23] The meeting between the AKP and the MHP ended without agreement, after which Davutoğlu returned the mandate to form a government back to the President on 18 August. In what was branded a ‘civilian coup’ by the CHP, Erdoğan refused to invite Kılıçdaroğlu to form a government as is required by the Constitution, despite the fact that there was still five days left before the 45-day period ended.[24][25] Instead, Erdoğan announced his intention to call an early election on 21 August, finalising his decision on 24 August.

Early election[edit]

The prospect for an early election arose as early as the eve of the previous election on 7 June 2015, as soon as it emerged that the AKP had lost its majority. The speculation was aided by the political polarisation in Turkey, which was perceived to have made it difficult for two parties to come together in a coalition.[26] Even in the event of a coalition, it was deemed unlikely that two parties could maintain an agreement for the length of the parliament, making an early election before the required date of June 2019 highly likely. During his speech on election night, MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli stated that his party was ready for an early election.[27]

It was widely observed by media commentators and opposition politicians that a vast majority of AKP politicians were in favour of going into an early election rather than forming a coalition government. President Erdoğan, the founder and former leader of the AKP, was widely seen to have observed a similar attitude.[28] MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli and many other opposition politicians criticised Erdoğan for interfering and allegedly attempting to tamper with the coalition efforts in order to force an early vote.[29] Polls also showed that a clear majority of AKP voters favoured an early election, though supporters of opposition parties were shown to have preferred a coalition.[30] The leader of the AKP’s coalition negotiation team Ömer Çelik was also seen as a proponent for an early election rather than a coalition, with Davutoğlu allegedly attempting but failing to remove him from his role due to his close relations with President Erdoğan.[31]

During the coalition negotiations, reports that the AKP were preparing for an early election resulted in numerous suggestions for possible polling dates, with the most likely (and eventually confirmed) option being in November 2015.[32] Other possible dates included Spring 2016, though AKP politicians claimed that elections could have been held as early as October 2015.[33][34] Speculation on the date resulted in Sadi Güven, the President of the Supreme Electoral Council of Turkey (YSK), stating that the YSK was prepared for an early election and had organised an election within 63 days in the past.[35] He stated that unless 9th article of the Parliamentary Elections Law was invoked, the most likely date for an early election would be the first Sunday after 90 days from President Erdoğan’s decision to call a snap election. Invoking the 9th article of the Parliamentary Elections Law could bring the date forward.[36] The YSK later issued a decision confirming that there were legal grounds for shortening the 90 day election timeline, after which they proposed to shorten the three-month period to two months and hold fresh elections on 1 November.[37] This date was later confirmed after Erdoğan called for early elections on 24 August.

Erdoğan’s decision for the date to be set for 1 November 2015 was ridiculed by opposition commentators since it would be the 93rd anniversary of the abolition of the Ottoman sultanate, which was deemed ironic due to what the opposition called Erdoğan’s perceived ‘desires’ to become a sultan through implementing a presidential system.[38]

This election will be the 7th early election called in the history of Turkish multi-party politics, with the previous 6 occurring in 1957, 1987, 1991, 1995, 1999 and 2002. It was observed that in every early election called, the governing party had always suffered a fall in their vote share.[39] The 2007 general election was also technically an early election, being called four months early after Parliament failed to elect a President, resulting in a more than 10-point increase in the AKP’s share of the vote.

Interim election government[edit]

Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu (C), Foreign Minister Feridun Sinirlioğlu (R) and Deputy Prime Minister Cevdet Yılmaz(L) address the United Nations in September 2015 as members of the interim election government

The November 2015 election is the first to be overseen by an interim election government, which must be formed in the event that the President calls an early vote if a government cannot be formed. With the June 2015 election being the only election after which politicians were unable to form a government, this is the first time the constitutional provision requiring an interim election government has been enacted. Serving Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu was tasked with forming the interim government on 25 August 2015, a day after Erdoğan announced the snap poll.[40]

As required by the Constitution of Turkey, the government must be a national unity government with all parties represented in Parliament taking part. Due to their significance in the lead-up to elections, the Ministers of Justice, the Interior and Transport must beIndependent. The remaining 22 ministries are allocated to each political party according to the number of MPs they have in Parliament. With the parliamentary composition at the time, the AKP was entitled to 11 ministries, the CHP to 5 and both the MHP and the HDP were entitled to 3 each. However, the CHP and the MHP refused to take part.[41] Davutoğlu sent invitations to CHP and MHP parliamentarians despite this, with MHP MP Tuğrul Türkeş surprisingly accepting the invitation and later being suspended from the MHP for disobeying the party line. All other CHP and MHP MPs declined invitations for ministerial positions, with their ministerial positions subsequently going to independents.

The government, sworn in on 28 August, is formed of 12 AKP MPs (including the Prime Minister), 12 Independents and 2 HDP MPs. Many of the independents, such as Energy Minister Ali Rıza Alaboyun, National Defence Minister Vecdi Gönül, Customs Minister Cenap Aşçı and Agriculture Minister Kutbettin Arzu are known to be active AKP supporters, though are not members of the party. Former AKP MPs Vecdi Gönül Kutbettin Arzu and Ali Rıza Alaboyun resigned from the AKP in order to become independent ministers.[42]

Electoral system[edit]

Turkey elects 550 Members of Parliament to the Grand National Assembly using the D’Hondt method, a party-list proportional representation system. In order to return MPs to parliament, a party must surpass the 10% election threshold. Parties that don’t win above 10% of the vote nationwide have their votes re-allocated to the party coming first in each electoral district, in most cases producing a large winners bonus for the party that comes first overall. The threshold does not apply to independent candidates.

Since the 2014 presidential election, Turkish expats have been given the right to vote in elections overseas. The total votes won by each party abroad, as well as their votes cast at customs gates, are proportionally allocated to the results in each electoral district according to the number of MPs they return. For example, Konya elects 14 MPs, which is 2.55% of the total elected (550). Therefore, 2.55% of all overseas votes will be allocated to Konya’s results, on the basis of the parties’ overseas vote share.

Electoral districts[edit]

Turkey is split into 85 electoral districts, which elect a certain number of Members to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. The Assembly has a total of 550 seats, which each electoral district allocated a certain number of MPs in proportion to their population. TheSupreme Electoral Council of Turkey conducts population reviews of each district before the election and can increase or decrease a district’s number of seats according to their electorate.

In all but three cases, electoral districts share the same name and borders of the 81 Provinces of Turkey, with the exception of İzmir,İstanbul and Ankara. Provinces electing between 19 and 36 MPs are split into two electoral districts, while any province electing above 36 MPs are divided into three. As the country’s three largest provinces, İzmir and Ankara are divided into two subdistricts while İstanbul is divided into three. The distribution of elected MPs per electoral district is shown below.[43]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contesting parties[edit]

The Supreme Electoral Council of Turkey (YSK) announced that 29 parties had met the requirements of eligibility to contest the general election. This was down from 31 in the previous election held in June. The Homeland Party (YURT-P), the Rights and Equality Party (HEPAR) and the Free Cause Party (HÜDA-PAR) all lost their eligibility, while theLabour Party (EMEP) regained its eligibility to contest, having lost it before the June 2015 election. 21 independents contested the election.[44]

Of the 29 parties eligible, 18 fielded candidates by the deadline of 17:00 local time on 18 September 2015. This was a drop of 2 since the June 2015 vote, which had been contested by 20 parties. Parties that had contested the election in June that did not field candidates this time round included the Anatolia Party (ANAPAR), the Homeland Party(YURT-P), the Social Reconciliation Reform and Development Party (TURK-P) and the Rights and Justice Party (HAP). The TURK-P submitted their candidate lists before the deadline but was barred from running due to a complaint made by the AKP, which claimed that the TURK-P’s logo was too similar to their own and thus confused voters.[45] TheCentre Party submitted their candidate lists but later decided to boycott the election.[46] Parties contesting the election that did not do so in June included the Great Union Party(BBP), which had entered the June 2015 election in a ‘National Alliance’ under the Felicity Party banner. The full list of parties contesting the election, ordered according to their position on the ballot paper, is as follows.

Pre-election alliances[edit]

The Justice and Development Party has signalled a possible electoral alliance with the Islamist Felicity Party (SP) and the Great Union Party (BBP) in an attempt to maximise their votes and guarantee a parliamentary majority.[48][49] The SP and BBP had run together in a ‘national alliance’ in the June 2015 election, winning 2.06% of the vote and falling far short of the 10% election threshold. Both the SP leader Mustafa Kamalak and the BBP leader Mustafa Destici stated that they would not close their doors on a possible alliance with the AKP, though commentators also claimed that such an alliance would not result in a significant increase in the AKP’s vote share since most SP and BBP supporters were heavily critical of the AKP in the first place.[50] Formal negotiations between the AKP and SP began on 3 September.[51] The AKP have also allegedly considered sending parliamentary candidacy invitations to former Islamist Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan’s son Fatih Erbakan and former Prime Minister Mesut Yılmaz to broaden the party’s appeal as much as possible.[52] On 15 September, talks between the AKP and SP ended unsuccessfully and the SP leader Mustafa Kamalak announced that they would contest the election alone, with the two parties failing to agree on the number of MPs that should be given to SP politicians.[53] The Rights and Justice Party (HAP) opted out of contesting the election and endorsed the AKP.[54]

The Republican People’s Party (CHP) leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu held a surprise meeting with Patriotic Party (VP) leader Doğu Perinçek over a possible alliance, with the two leaders agreeing to continue negotiations.[55] It was also rumoured that the CHP could form an alliance with the Rights and Equality Party (HEPAR), with the party’s founderOsman Pamukoğlu claiming that he would boost the CHP’s vote by 3–4%.[56][57] It was also reported that a possible alliance with the Independent Turkey Party (BTP) could take place, with BTP leader Haydar Baş becoming an MP from the CHP party lists.[58] The CHP stated on 16 September that the party would not contest the election in an alliance, with the VP subsequently announcing that they would be contesting the election alone.[59]

The Great Union Party (BBP), having been open to talks with the AKP, also sought an alliance deal with the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) in order to by-pass the 10%election threshold. It was reported that the MHP could offer the BBP two or three prime spots on their candidate lists with certain chances of election.[60]

The left-wing Labour Party (EMEP) announced that they would not be taking part in the election, repeating its June 2015 tactic of forming an election alliance with the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP).[61] It was reported that the HDP’s Kurdish Islamist rival Free Cause Party (HÜDA-PAR) would form an alliance with the AKP, though this again failed to materialise and the HÜDA-PAR ended up not contesting the election.[62]

Several parties, many of which were not eligible to field their own candidates, instead endorsed other parties. A full list of endorsements are shown in the following table.

| [hide]Party political endorsements | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Boycotts[edit]

The Anatolia Party (ANAPAR), which had broken away from the Republican People’s Party, announced that it would not contest the election. The party’s leader Emine Ülker Tarhan claimed that they would not take part in an election called on the basis of Erdoğan’s desire for a presidential system or the deaths of Turkish soldiers fighting the PKK. The party announced that it would not play Erdoğan’s ‘game’ or participate in an election system that they criticised. Tarhan also referred to the safety of the election as ‘debatable’.[70]

Both the Homeland Party (YURT-P) and the Rights and Equality Party (HEPAR) announced that they would boycott the elections, voicing concerns over President Erdoğan’s controversial tactics and speculating that a new election would not give a different result.[71][72] However, it was also noted that the two parties were not eligible to contest the election in the first place.[71] The left-libertarian Freedom and Solidarity Party (ÖDP) also announced that it would not contest the election.[73] The Kurdish Islamist Free Cause Party (HÜDA-PAR) also ruled out contesting the election, claiming that it would not be a healthy means of gauging voters’ opinions under the security circumstances in the south-east of the country.[74]

Despite submitting their candidate lists to the YSK before the deadline, the Centre Party later announced on 22 September that they were withdrawing from the election, claiming that they would instead be diverting efforts to improving their local branches and support. The party’s leader Abdurrahim Karslı issued a statement criticising the AKP for ignoring the will of the people in the June 2015 vote and calling a new election, accusing the government of ‘thoughtlessness and waywardness’ in spending over ₺2 billion on calling the new vote.[46]

TURK Party controversy[edit]

Despite polling well below the 10% election threshold, the Social Reconciliation Reform and Development Party (TURK-P) took 72,701 votes in the June 2015 election. The unusually high votes cast for the party (especially in areas where the party had no campaign events such as Trabzon), was attributed to illiterate voters mistaking the party’s logo for that of the AKP.[75] Following the election, the AKP took the TURK Party to court over the similarity in logos, with the TURK Party nevertheless being declared eligible to contest the November election by the Supreme Electoral Council of Turkey (YSK). One day after submitting their candidate lists, the TURK Party was blocked from contesting the election by a court that ruled in favour of the AKP and declared the TURK Party’s logo to be too similar to that of the AKP.[76] The decision was criticised by the opposition and was seen as an attempt by the AKP to increase their vote share through undemocratic means by eliminating parties that posed a direct threat to the AKP’s votes. This claim was made again after the YSK ruled that the TURK Party was in fact not eligible to contest the election in the first place, even though they had previously stated otherwise.[77]

Campaigns[edit]

Justice and Development Party[edit]

Party leader Ahmet Davutoğlu at his party’s 5th Ordinary Congress, 12 September 2015

The Justice and Development Party (AKP) began their election campaign with an ordinary congress held on 12 September 2015. Party leader and serving Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu stood as a candidate for re-election, though an apparent disagreement with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan over Davutoğlu’s provisional Central Decision Executive Board (MKYK) candidates caused Erdoğan’s special advisor Binali Yıldırım to begin collecting signatures for a possible leadership bid. The disagreements were allegedly solved at the last minute, after which Yıldırım withdrew as a potential candidate. The party’s by-laws were also changed to stop the 25th Parliamentary term counting towards AKP parliamentarians’ three-term limit on the grounds that the parliamentary session only lasted for four months. The three-term limit was thus lifted for MPs in this election.

Critics accuse the AKP of purposely ending the solution process and sparking an outbreak in violence between the Turkish Armed Forces and the militant Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in order to win back disaffected voters from the Nationalist Movement Party(MHP).[9][10][11][12][13] The AKP has also been accused of attempting to render the security situation in south-eastern Turkey, where there had been a huge swing from the AKP to the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) in June’s election, unfit for peaceful elections in order to reduce turnout and thus the HDP’s vote share.[78][79][80][81] The opposition have accused the AKP of ‘punishing’ the south-east, especially the southern town of Cizre where the HDP won 85% of the vote in June, by imposing prolonged curfews lasting nearly a week to combat PKK militants there.[82][83]

Despite the short-lived tenure of the 25th Parliament, it was observed that 40% of the AKP’s party candidate lists fielded in April for the June 2015 election had been changed by September. Notable changes included the candidacies of many of the party’s high-profile founders such as Binali Yıldırım, Faruk Çelik and Ali Babacan, all of which had been unable to seek re-election in June for reaching their three-term limit. Former MHP MP Tuğrul Türkeş, who served as a Deputy Prime Minister in the interim election government, also became an AKP candidate from Ankara. Abdurrahim Boynukalın, who had been heavily criticised for his role in the assault on the Hürriyet newspaper headquarters in September 2015, was stripped from the AKP lists, though he later claimed that he himself had not applied to become a candidate.[84] Turkish folk music singer İbrahim Tatlıses, who had applied to become an AKP candidate for a third time, failed to make it onto the party lists.[85]

The AKP announced their manifesto on 5 October, with many media outlets being refused an invitation. With the slogan ‘Haydi Bismillah[disambiguation needed]‘, the AKP announced a new minimum wage of ₺1,300 having initially refused to announce a rise for the June election, the party also pledged more public sector jobs, free internet for young people, to grant legal status to Alevi Cemevis and to rewrite the constitution to place a greater emphasis on democracy and human rights.[86] The AKP’s election song ‘Haydi Bismillah’ was banned by the YSK on 24 September on the grounds that it used religious aspects in a political campaign, following a complaint by the CHP.[87]

Republican People’s Party[edit]

CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğluannouncing the party’s election manifesto on 30 September

CHP politicians Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu,Murat Karayalçın, Faik Öztrak and Selin Sayek Böke at a TÜSİAD panel discussion on 15 October

The Republican People’s Party (CHP) announced their election manifesto on 30 September and renewed their pledge to increase the national minimum wage to ₺1,500. The party adopted the slogan ‘Önce İnsan, Önce Birlik, Önce Türkiye,’ which translates to ‘People first, unity first, Turkey first’. Building on their June 2015 manifesto, which had been criticised for omitting policies for young people, the CHP also launched policies to increase internet freedom and offer financial relief to students going into debt during higher education.[88][89] The emphasis on young people was seen as significant by the polling company Andy-Ar, who stated that both the CHP and AKP had failed to capture the young vote despite a surge of young registered voters since 2002. Nevertheless, experts commented that the party’s policies on solving the unrest in the south-east of the country to be insufficient.[90] Party leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu also appeared on numerous question-and-answer shows with an audience made up of predominantly young people and students.[91]

The party held its first electoral rally in Mersin on 3 October 2015, focusing mainly on the issues of terrorism and the economy.[92]Although the party produced an election song to accompany their Önce Türkiye slogan, events such as the manifesto announcement and rallies took place in rather subdued atmospheres in respect for fallen soldiers during the conflict in the south-east.[93][94] During the campaign, Kılıçdaroğlu revealed that the AKP had asked for assurances that the CHP would not pursue legal proceedings against President Erdoğan or his family should they enter a coalition, to which the CHP responded that it was up to the independent judiciary to pursue such proceedings if necessary.[95] The party significantly toned down their election campaign by suspending their planned electoral rallies following the Ankara bombing on 10 October.[96]

The CHP attracted criticism from Turkish nationalists and the AKP for its support for the HDP following the escalation of conflict in the south-east, with CHP MP İhsan Özkes resigning from his party shortly after June’s election and heavily criticised the party for its closeness to the HDP.[97] Patriotic Party (VP) leader Doğu Perinçek claimed after unsuccessful alliance negotiations with the CHP that he had ‘failed to rescue the CHP from the clutches of the HDP.’[98] The HDP had also signalled a possible coalition with the CHP.[99]

Nationalist Movement Party[edit]

MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli announcing his party’s election manifesto on 3 October

The Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) set out their party lists in September, in which prominent MHP Member of Parliament Meral Akşener was stripped of her candidacy.[100] The move was attributed to party leader Devlet Bahçeli attempting to avoid strong rivals in any future leadership contest, causing a backlash on Twitter with the slogan “No Akşener, no vote either!”.[101]

The MHP unveiled their manifesto on 3 October, renewing their commitment to raising the minimum wage to ₺1,400 and pledging to guarantee a job to at least one member of each family. The party also pledged to abolish university entrance exams and to give two one-off ₺1,400 payments to pensioners every year. On the issue of the growing unrest, the MHP produced a short video showing AKP and HDP politicians making false statements and contradicting themselves, in order to give the message that the MHP had been right to oppose the solution process after all.[102] In the event that the election produced the same outcome as the June election, MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli claimed that they would form a coalition with any party apart from the HDP this time round.[103]

Peoples’ Democratic Party[edit]

HDP supporters, led by co-leaderSelahattin Demirtaş, marching to Cizre in September 2015 after their convoy was stopped by the police.

HDP co-leaders Selahattin Demirtaşand Figen Yüksekdağ after announcing the party’s manifesto on 1 October

The Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) co-leader Figen Yüksekdağ announced that the HDP was targeting a vote share close to 20%.[104] Following a Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) attack in Dağlıca that killed 16 soldiers, the HDP’s other co-leader Selahattin Demirtaş cancelled a planned overseas trip in Germany and returned to Turkey.[105][106][107] The party, which has long been accused of supporting and maintaining links with the PKK, received criticism in the run-up to the elections after a breakout of violence in the south-east, with the governing AKP pursuing a strategy of associating the HDP as much as possible with the PKK’s acts of terrorism. However, sources have maintained that the HDP maintains little control over PKK militants, with Demirtaş calling for both sides to return to peace through restarting the solution process and calling for the PKK to lay down their arms.[108]

The HDP announced its manifesto on 1 October, beginning with the slogan ‘İnandına HDP, İnadına barış’, which roughly translates to ‘We insist on the HDP, we insist on peace!’. Their manifesto centred around the issues of democracy, peace and justice, with a commitment to restart the solution process.[109] The manifesto also pledged actions on workers’ safety standards, tackling corruption and to reform the penal code. The HDP also made a commitment to recognising the Armenian Genocide, a pledge that was criticised by pro-government newspapers.[110]

Other parties[edit]

The leader of the Kurdish federalist Rights and Freedoms Party (HAK-PAR), Fehmi Demir, died in a traffic accident on 25 October 2015, on the last day of overseas voting.[111] The HAK-PAR had fielded candidates in 78 electoral districts and had won 60,000 votes in the June election, falling well below the 10% boundary needed to win seats.

Opinion polls[edit]

Opinion polling mainly showed that the AKP had increased their popularity since June by around 2–3% of the vote, though this was not enough to give them a parliamentary majority according to seat predictions. On the other hand, some polls (especially pro-opposition pollsters such as SONAR and Gezici) showed the AKP to have fallen below the 40% mark, with Gezici claiming that the AKP would win between 35–39% of the vote. Most pollsters, including those known to be close to the government, showed a 2–3% increase in the CHP’s vote. The MHP’s vote share was either shown to be stable or to have retracted by around 2–3%, which was attributed to the party’s much criticised stance during the June–July 2015 Turkish Parliament speaker elections and the ending of the Solution process. Despite attempts to tarnish the HDP through accusing it of direct relations with the PKK, the HDP was shown in every poll to remain somewhat comfortably above the 10% threshold, making an AKP majority unlikely.

Restrictions on opposition pollsters[edit]

On 19 September, a group of Gezici employees conducting a poll were arrested by the police for allegedly not having the required documents to conduct polling research and were released shortly after. Gezici owner Murat Gezici denied these claims, stating that the company had all the required documentation since 2011.[112] The arrests came just before Gezici announced the results of their poll, which showed the AKP polling at between 35 and 39%.[113] With the government having been accused of trying to conduct a ‘perception operation’ by releasing biased polling results in past elections, many opposition journalists and commentators accused the government of trying to cover up their actual vote share by obstructing pro-opposition pollsters from conducting their research.[114]

Final predictions before the vote[edit]

| Party | A&G 24–25 Oct |

AKAM 16–20 Oct |

Denge 10–15 Oct |

Gezici 24–25 Oct |

Kurd-Tek 17–21 Oct |

Konda 24–25 Oct |

Konsensus 13–19 Oct |

MAK 12–17 Oct |

MetroPoll 22–24 Oct |

ORC 21–24 Oct |

SONAR 8–15 Oct |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKP | 47.2 | 40.5 | 43.4 | 43.0 | 39.1 | 41.7 | 43.0 | 43.5 | 43.3 | 43.3 | 40.5 | |

| CHP | 25.3 | 28.2 | 25.9 | 26.1 | 28.1 | 27.9 | 28.6 | 27.8 | 25.9 | 27.4 | 27.3 | |

| MHP | 13.5 | 14.3 | 13.7 | 14.9 | 14.4 | 14.2 | 13.1 | 13.6 | 14.8 | 14.0 | 15.2 | |

| HDP | 12.2 | 14.2 | 13.6 | 12.2 | 14.2 | 13.8 | 11.9 | 12.1 | 13.4 | 12.2 | 13.1 | |

| Others | 1.8 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 3.9 | |

|

Lead

|

21.9 | 12.3 | 17.5 | 16.9 | 11.0 | 13.8 | 14.4 | 15.7 | 17.4 | 15.9 | 13.2 | |

| Party | A&G 24–25 Oct |

AKAM* 16–20 Oct |

Denge 10–15 Oct |

Gezici 24–25 Oct |

Kurd-Tek* 17–21 Oct |

Konda 24–25 Oct |

Konsensus 13–19 Oct |

MAK 12–17 Oct |

MetroPoll* 22–24 Oct |

ORC 21–24 Oct |

SONAR 8–15 Oct |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKP | 288 | 254 | 271 | 269 | 251 | 260 | 272 | 273 | 269 | 271 | 255 | |

| CHP | 128 | 140 | 136 | 135 | 149 | 144 | 146 | 142 | 134 | 140 | 140 | |

| MHP | 60 | 69 | 63 | 69 | 66 | 63 | 57 | 60 | 67 | 62 | 73 | |

| HDP | 74 | 87 | 80 | 77 | 84 | 83 | 75 | 75 | 80 | 77 | 82 | |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

|

Majority

276 to win |

26 | Hung | Hung | Hung | Hung | Hung | Hung | Hung | Hung | Hung | Hung | |

* These polls included a detailed projection of seat distribution in the poll itself. The rest of the results are the results of the projected vote shares being applied to an election simulator on the basis of the June 2015 election outcome.

Controversies[edit]

Security concerns[edit]

Turkish Army vehicles in Diyarbakırfollowing the collapse of the solution process in July 2015

Aftermath of a PKK terrorist attack inDiyarbakır in August 2015

Following a suicide bombing in the south-eastern town of Suruç that killed 32 people, the government authorised airstrikes against theIslamic State of Iraq and the Levant as well as the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK). The government had been involved in ceasefire negotiations with the PKK since late 2012, with the airstrikes causing the negotiations, known as the solution process, to break down. The abandoning of both the solution process with the Kurdish rebels and the policy of inaction against ISIL by the Turkish government led to a resumption of violence in the south-east, with PKK militants resuming attacks on Turkish military and police positions.[115] Over 90 military or police personnel had been killed by 6 September 2015, raising concerns about whether peaceful elections could be held in the region.[116][117][118] The pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) co-leader Selahattin Demirtaş claimed that the conditions in the south-east were not adequate to hold peaceful elections, with party officials investigating the region having returned with negative reports.[119] In early September, three Republican People’s Party (CHP) MPs visited Van, Hakkâri and the district ofYüksekova. Their report, which contained accounts from the Governor of Hakkâri and the Kaymakam of Yüksekova, stated that the HDP-run municipalities in the region were openly recruiting militants for the PKK and consulting them before taking decisions. The report also documented cases of PKK youth wing (YDG-H) members attempting to militarise the region, smuggling to finance their operations and forcing individuals to conduct PKK propaganda.[120]

On 11 October 2015, the PKK announced a one-sided ceasefire in order to guarantee peaceful elections. The ceasefire was rejected by the Turkish government, which continued to conduct military operations against PKK positions.[121]

Press freedom and censorship[edit]

Protest banners at the headquarters of raided media company Koza İpek, 28 October 2015

Although many commentators saw the AKP’s loss of a majority as a welcome development in terms of press freedom, growing censorship of pro-opposition media outlets in the run-up to the November election attracted both national and international concern. In September, international controversy arose over the arrest of 3 Vice News journalists on terrorism charges while covering the surge in unrest in south-eastern Turkey.[122] On 1 September, police raided the headquarters of Koza İpek Holding, known for its close relations with the Gülen Movement with which the AKP has been in political conflict since 2013. TV channels Kanaltürk and Bugün were among those targeted, with the raids being criticised by Reporters Without Borders and several national journalists’ associations.[123][124]Kozan İpek was again stormed by police on 28 October after a court ordered the seizure of the company’s assets for ‘terror financing’ and ‘terror propaganda’. Kanaltürk and Bugün were subsequently taken off-air. European Parliament President Martin Schulz tweetedthat he was “deeply concerned” about the raid.[125]

On 14 September, an edition of the magazine Nokta was impounded on for allegedly ‘insulting the President’ and publishing ‘propaganda for an armed terrorist organisation’. The front cover featured a doctored image of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan taking a selfie in front of a soldier’s funeral, a reference to allegations that the government had purposefully resumed armed conflict with the PKK in order to win back nationalist votes.[126]

In the early hours of 1 October, Hürriyet columnist and the presenter of the political talk show Tarafsız Bölge (Neutral Area), Ahmet Hakan, was attacked by four people outside his home.[127] It emerged later that three of the four attackers were AKP members, who were later suspended from the party.[128][129] 7 people were taken into custody for the attack, with only one being arrested. One of the suspects involved claimed that the police had paid them ₺25,000 to carry out the attack, alleging that the National Intelligence Organisation (MİT), the police and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan were all aware of the plot.[130]

On 3 October, thousands of journalists as well as members from numerous journalism associations held a demonstration at Taksim Square to protest the growing censorship of the press.[131][132]

The state news agency TRT was identified by the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) as giving 10 times more coverage to the AKP than to the opposition parties.[133] The TRT also came under fire for holding an interview with AKP leader Ahmet Davutoğlu after the coverage ban came into effect at 00:00 local time on 31 October.[134] This was in contrast to CNN Türk’s interview with CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu broadcast at the same time, which duly ended at 00:00 as required.[135] The TRT’s alleged bias caused MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli to reject a TRT microphone in protest while making a statement in his hometown ofOsmaniye.[136]

Political violence[edit]

Aftermath of the attacks on the Hürriyetnewspaper headquarters in early September 2015

On 6 September, a group of 200 AKP supporters attacked the headquarters of Doğan Media Centre, which houses the offices of the newspaper Hürriyet. The newspaper had published a news story about an interview with Erdoğan by another TV channel shortly after 16 soldiers were killed by roadside bombs in Dağlıca. Erdoğan’s comments, which included a claim that the attacks would have never had happened had the AKP won 400 seats in the June 2015, caused uproar and the newspaper was accused by AKP supporters of misquoting the President.[137] AKP MP and Youth Wing leader Abdurrahim Boynukalın led the mob against Hürriyet, drawing heavy criticism and subsequently being sent to court for inciting hatred and vandalism.[138] Another attack by a group of 100 protestors on Hürriyet occurred on 8 September in both their İstanbul and Ankara headquarters, this time opening fire on the building.[139][140] 6 people were arrested for the role in the attacks.[141]

The archives department of the HDPheadquarters after being subject to an arson attack by Turkish nationalists in September 2015

After the Turkish military suffered heavy casualties in fights with the PKK in both Dağlıca and Iğdır, nationalist protestors staged demonstrations and many attacked HDP office branches in protest at the HDP’s links with the PKK. The HDP’s headquarters was also subject to an arson attack, though the ensuring fire was quickly put out.[142] Selahattin Demirtaş announced on 9 September that 400 HDP branch offices had come under attack in the last two days and accused the AKP’s leaders of trying to push the country into civil war.[143][144][145] However, the Mayor of Cizre Leyla İmret, a member of the HDP’s fraternal Democratic Regions Party (DBP), claimed that they would begin a civil war against Turkey from Cizre.[146] Fights between HDP and nationalists resulted in both deaths and injuries, while the workplace of a former HDP candidate was set alight by protestors.[147][148]

In addition to the HDP, the offices of CHP branch offices in Sincan and Konya came under attack, with the offices and vehicles outside them being heavily vandalised. It was alleged by the CHP that the perpetrators of the attacks in Sincan included members of the Ottoman Hearths (Osmanlı Ocakları).[149] On 26 October, gunmen driving past the CHP headquarters in Ankara fired five rounds at the building, though no-one was killed or injured. The CHP’s leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu stated that his party would not be intimidated by the attack while other parties expressed their condemnation.[150]

During early voting, a clash took place outside the Turkish embassy in Tokyo in October 2015 between Kurds in Japan and Turks in Japan which began when the Turks assaulted the Kurds after a Kurdish party flag was shown at the embassy.[151][152][153][154][155]

Safety and distribution of ballot boxes[edit]

In September 2015, the government allegedly began pressuring the YSK to divert voters living in villages linked to the south-eastern district of Cizre to the town centre instead, citing security concerns.[156] Cizre had been under an 8-day curfew while armed forced carried out a security operation against PKK militants before the government requested the ‘merging’ of ballot boxes. Such a decision would require villagers living in rural settlements having to make their way to the town centre to cast their vote instead, drawing strong opposition from the HDP. Several other district electoral councils in the south-east began taking decisions to transfer ballot boxes in embattled towns to safer areas, with their decisions also being supported on occasions by the CHP. However, both the CHP Supreme Electoral Council representative and the President of the YSK himself stated that the decisions had no legal basis, stating that the YSK had to be consulted before such decisions could be made.[157][158] On 3 October, the YSK voted against transferring ballot boxes, drawing heavy criticism from the AKP.[159]

Distribution of goods[edit]

On 31 October, a day before polling day, the government began distributing free coal in Malatya.[160] The distribution of free resources such as coal, pasta and other accessories to voters in the run-up to elections has been a long-time controversy in Turkey, with the opposition accusing the governing AKP of attempting to ‘buy-off’ voters using public funds during the 2014 presidential election and the 2014 local elections. CHP Malatya MP Veli Ağbaba called the distribution ‘a sign of the AKP’s desperation’ and called on those responsible to justify their actions.[161]

Conduct[edit]

CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu voting in Ankara

Voting began at 08:00 local time and ended at 17:00 throughout the country and including prisons, with eastern provinces beginning voting an hour early at 07:00 and ending at 16:00. 175,006 ballot boxes were used and 75,288,955 ballot papers were printed in preparation, despite the total electorate being just over 56 million.[162][163] Voters were allowed to vote after 17:00 (or 16:00 in eastern provinces) only if they had joined the queue to do so beforehand. Although there have been penalties for not voting in previous elections such as the 2010 constitutional referendum and the 2014 presidential election, the YSK did not set a fine for abstaining in this election.[164]

In the run-up to the election, the government declared three days of holidays, on the Thursday before polling day as well as the Monday after. This, combined with the weekend and taking one day off on Friday, totalled to five days of holiday, with many critics accusing the government of purposely trying to decrease turnout by encouraging voters to go on a holiday away from their polling stations in order to benefit the AKP. However, tourism professionals claimed that hotels in the tourist areas of İzmir and Antalya were only 10% booked, much lower than usual for the time of year, with just 5% of the bookings made by Turkish nationals.[165]

Summertime daylight saving was also extended until 8 November in order to allow the election to take place during daylight, although most other countries added an hour on Sunday 25 October. This caused confusion amongst citizens since automatic clocks defied the Turkish government’s decision and went back an hour on 25 October in conformity with the global end to daylight saving time.[166]

The lowest number of votes were cast in ballot box number 2224 in the village of Yolveren, Gaziantep Province, where 16 voters were registered but only two (the village muhtarand his wife) cast their votes.[167]

Election observation[edit]

CHP former MP and special advisorErdal Aksünger giving information on the CHP’s new count shadowing system on 29 October

In the run-up to the election, both the CHP and the HDP developed computer systems that allowed the party to shadow the official election results by running their own counts alongside the Anadolu Agency and the Cihan News Agency. The systems would allow both parties to input data from hard copy statements of results for each ballot box to ensure that there was no discrepancy between the actual counted votes and the results entered into the YSK’s SEÇSİS system.[168][169]

On 5 September, the HDP requested that the YSK place cameras to film the vote counting procedures in 126 ‘high security risk’ areas.[170] Their proposal was rejected on 14 September.[171] On 31 October, a day before the election, the YSK rejected a complaint made by two unknown individuals, who argued that it was unlawful for independent election observers such as Oy ve Ötesi to observe the voting or counting process by obtaining observer passes from political parties.[172] Similar to the June 2015 election, volunteer observer groups such as Oy ve Ötesi were supported by the Liberal Democrat Party (LDP) and the Democrat Party (DP), which gave volunteers the political party passes needed to observe the voting or counting process.[173]

Overseas and customs voting[edit]

Turkish expatriates in the United Statesvoting at the consulate in New York City in October 2015

Overseas voting began in 54 different countries on 8 October, coming to an end on 25 October 2015.[174] It was observed that there had been a significant increase in the number of expatriates casting their votes overseas in comparison to the June 2015 general election, with turnout reaching around 43%.[175] Voting at customs gates also began on 8 October and continued until polls closed on 1 November.

The overseas and customs votes are combined and proportionally allocated throughout each of the 85 electoral districts of Turkey in relation to the number of MPs they elect. For example, Konya elects 14 MPs, which is 2.55% of the total (550) that are elected nationwide. This means that 2.55% of each party’s votes gained overseas will be added to their respective results in Konya. In the 7 June election, the MHP lost two MPs after overseas votes had been added to national totals, one to the HDP in Kocaeli and one to the AKP in Amasya. Meanwhile, the CHP lost one MP to the AKP in İzmir.[176] Abdulkadir Selvi, from ANAR Research, claimed that the AKP would gain 9 or 10 MPs due to the overseas votes.[177]

Electoral fraud[edit]

Amasya scandal[edit]

At 17:00 local time on 31 October 2015, the Mayor of the Göynücek district of Amasya, Kemal Şahin, published a photo on his Facebook account showing a ballot paper stamped for the AKP, with the caption ‘I’ve cast my vote. May it go well’.[178] The post caused a scandal since the picture of the vote had been published 15 hours before voting actually began, having also violated the legal restrictions on the photographing of stamped ballot papers. Subsequent investigations found that AKP supporters in Amasya had began casting their votes as early as 01:15 local time.[179] The electoral district of Amasya was particularly critical since the MHP had lost one MP to the AKP by just 600 votes in June’s election, with the MHP top candidate Mehmet Sarı claiming that they were always suspicious of the AKP planning malpractice to not lose the hotly contested seat.[180] Sarı later stated that he had phoned the Mayor, who allegedly tried to laugh off the matter and claimed that he had printed the ballot paper off the internet. Both Sarı and the Amasya CHP provincial president Hüseyin Duran submitted criminal complaints against Şahin.[181]

Results[edit]

The results were widely referred to as a ‘shock’ win for the AKP, which defied every poll to win a comfortable parliamentary majority with 316 seats in Parliament.[182] The election was described as a huge personal victory for President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who was seen to have been ‘punished’ by the electorate in the June election.[183] Most opinion polls showed the AKP to be polling between 38–43%, with only a few polls showing the party to be heading for a narrow parliamentary majority.[184][185] Winning 49.4%, the party’s performance bore resemblance to their 2011 general election result of 49.8%, though also broke the record for winning the most number of votes in any Turkish election by winning over 23 million votes. The election also came as a shock to the MHP and the HDP, both of which were widely expected to safeguard their vote shares and remain comfortably above the 10% election threshold. The MHP, having polled 16.29% in the June election, suffered a decrease of 4 percentage points and won just under 12% of the vote, while the HDP seemed to have fallen below the threshold at some points during the election count.[186][187] Nevertheless, the HDP won 59 seats with 10.7% of the vote, coming fourth in terms of votes but third in terms of seats, while the MHP lost almost half its parliamentary representation and won just 41 seats.[188] The CHP, which had been expected to win between 27–28% of the vote according to many pollsters, fell short of expectations despite slightly improving on their June 2015 result, winning 134 seats with 25.4% of the vote.[citation needed]

The heavy defeat for the MHP was attributed to the party’s stance since the June 2015 election. MHP leaderDevlet Bahçeli had come under heavy criticism for rejecting all possible coalition scenarios and refusing any opportunities to take his party into government, with the media referring to Bahçeli’s stance as saying ‘no to everything’.[189][190] He was also criticised for basing his party’s policy to do the exact opposite of the HDP, for example during the June–July 2015 Parliamentary Speaker election.[191] Distancing some of the MHP’s more popular politicians such asSinan Oğan and Meral Akşener from the party’s candidate lists also caused controversy.[192] Media commentators claimed that the dangerous decrease in the HDP’s vote share was due to voters punishing the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), with which the HDP is accused of having informal links.[193]

Overall results[edit]

| ↓ | ||||

| 317 | 134 | 59 | 40 | |

| AKP | CHP | HDP | MHP | |

| Party | Vote | Seats | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviation | Party name in Turkish |

Leader(s) | Votes | % | swing | Elected | % of total | ± since 31 Oct |

± since Jun 2015 |

|

|

AKP

|

Justice and Development Party Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi |

23,669,933 | 49.48 | 317 | 57.64 | |||||

|

CHP

|

Republican People’s Party Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi |

12,108,801 | 25.31 | 134 | 24.36 | |||||

|

MHP

|

Nationalist Movement Party Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi |

5,691,035 | 11.90 | 40 | 7.27 | |||||

|

HDP

|

Peoples’ Democratic Party Halkların Demokratik Partisi |

5,144,108 | 10.75 | 59 | 10.73 | |||||

|

SP

|

Felicity Party Saadet Partisi |

325,910 | 0.68 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

|

BBP

|

Great Union Party Büyük Birlik Partisi |

262,723 | 0.55 | N/A | 0 | 0.00 | N/A | N/A | ||

|

VP

|

Patriotic Party Vatan Partisi |

119,591 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

|

HAK-PAR

|

Rights and Freedoms Party Hak ve Özgürlükler Partisi |

(died 25 October 2015)

|

110,161 | 0.23 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

|

HKP

|

People’s Liberation Party Halkın Kurtuluş Partisi |

85,137 | 0.18 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

|

DP

|

Democrat Party Demokrat Parti |

69,352 | 0.14 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

|

KP

|

Communist Party Komünist Parti |

53,970 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| Independents Bağımsızlar |

51,210 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||||

|

BTP

|

Independent Turkey Party Bağımsız Türkiye Partisi |

51,028 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

|

DSP

|

Democratic Left Party Demokratik Sol Parti |

32,044 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

|

LDP

|

Liberal Democrat Party Liberal Demokrat Parti |

27,498 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

|

MP

|

Nation Party Millet Partisi |

20,034 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

|

DYP

|

True Path Party Doğru Yol Partisi |

14,087 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| Total | 100.00 | 550 | 100.00 | |||||||

| Valid votes | ||||||||||

| Invalid / blank votes | ||||||||||

| Votes cast / turnout | ||||||||||

| Abstentions | ||||||||||

| Registered voters | ||||||||||

| Source: | ||||||||||

Nationwide results[edit]

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reference: Anadolu News Agency (provisional results)

Overseas and customs results[edit]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parliamentary composition[edit]

| Party | 25th Parliament (23 June 2015 – ) |

26th Parliament (TBD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elected | At dissolution | Elected | |||

| AKP | Justice and Development Party |

258 / 550

|

258 / 550

|

317 / 550

|

|

| CHP | Republican People’s Party |

132 / 550

|

131 / 550

|

134 / 550

|

|

| HDP | Peoples’ Democratic Party |

80 / 550

|

80 / 550

|

59 / 550

|

|

| MHP | Nationalist Movement Party |

80 / 550

|

79 / 550

|

40 / 550

|

|

| Independents |

0 / 550

|

2 / 550

|

0 / 550

|

||

| Total | 550 | 550 | 550 | ||

| Since the June election, CHP MP İhsan Özkes resigned from his party,[194] and MHP MP Tuğrul Türkeş resigned from the MHP.[195] | |||||

Aftermath[edit]

International reactions[edit]

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Presidential chairman Bakir Izetbegović claimed that the Turkish people had voted for stability, having congratulated the AKP on their election victory.[196]

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Presidential chairman Bakir Izetbegović claimed that the Turkish people had voted for stability, having congratulated the AKP on their election victory.[196] Ethiopia: Government spokesperson Getachew Reda welcomed the AKP’s victory.[197]

Ethiopia: Government spokesperson Getachew Reda welcomed the AKP’s victory.[197] Germany: German Chancellor Angela Merkel phoned Ahmet Davutoğlu to congratulate him on his election victory.[198]

Germany: German Chancellor Angela Merkel phoned Ahmet Davutoğlu to congratulate him on his election victory.[198] Greece: Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras phoned Ahmet Davutoğlu and congratulated him on his election victory, while voicing his intentions to visit Turkey to discuss the worsening European migrant crisis.[199]

Greece: Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras phoned Ahmet Davutoğlu and congratulated him on his election victory, while voicing his intentions to visit Turkey to discuss the worsening European migrant crisis.[199] Montenegro: Prime Minister Milo Đukanović congratulated the AKP on their electoral success and wished the Turkish people well following the election.[200]

Montenegro: Prime Minister Milo Đukanović congratulated the AKP on their electoral success and wished the Turkish people well following the election.[200] Pakistan: Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif congratulated Davutoğlu and expressed his willingness to advance Turkish-Pakistani relations on all fronts.[201]

Pakistan: Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif congratulated Davutoğlu and expressed his willingness to advance Turkish-Pakistani relations on all fronts.[201] Palestine: Mahmud Abbas, the President of Palestine, phoned Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to congratulate the AKP on its election performance.[202]

Palestine: Mahmud Abbas, the President of Palestine, phoned Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to congratulate the AKP on its election performance.[202] Iran: Marziyeh Afgham, the spokesperson for the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, congratulated the government and the Turkish people for holding successful parliamentary elections with high turnout. Afham stated that Iran hoped to develop bilateral relations with the country under the new government.[203]

Iran: Marziyeh Afgham, the spokesperson for the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, congratulated the government and the Turkish people for holding successful parliamentary elections with high turnout. Afham stated that Iran hoped to develop bilateral relations with the country under the new government.[203] United States: White House press spokesman Josh Earnest offered his congratulations to Turkey and stated that the US was prepared to work with the new government and elected MPs. He also stated that the concerns over media censorship and bias had been expressed to the government.[204]

United States: White House press spokesman Josh Earnest offered his congratulations to Turkey and stated that the US was prepared to work with the new government and elected MPs. He also stated that the concerns over media censorship and bias had been expressed to the government.[204]

References[edit]

FEELING SAFER YET, CANADIANS? Your new shiny pony ‘prime minister’ says “Islamic terrorists should NOT lose their Canadian citizenship”

CTV News has obtained a recording leaked by the Conservative Party of Justin Trudeau’s answer in July to a question about Bill C-24, a law that allows dual citizens – those who are convicted terrorists – to be stripped of their Canadian citizenship and deported.

CTV News “The Liberal Party believes that terrorists should get to keep their Canadian citizenship … because I do,” Trudeau told a Winnipeg town hall in July. “And I’m willing to take on anyone who disagrees with that.

C-24 allows the federal government to revoke the citizenship of dual citizens convicted of terrorism, treason or espionage inside or outside of Canada. It also applies to dual citizens who take up arms against Canada by joining an international terrorist organization or fighting with a foreign army.

One member of the Toronto 18, convicted of being involved in the plot to bomb the city, has already been paroled. The so-called mastermind behind the plot is eligible for release next year, and the government announced Friday plans to revoke his citizenship and deport him to Jordan – the first such case in Canada since the new law was enacted.

The Conservatives criticize Trudeau for telling his Winnipeg audience the revocation of citizenship allowed in Bill C-24 is about “good behaviour,” when it actually is intended to target dual citizens who have been convicted of terrorism here or abroad convicted of treason, spying, or armed conflict against Canada.

“Mr. Trudeau’s position suggests that he really doesn’t value Canadian citizenship,” Conservative candidate Jason Kenney said. “If you can take up arms against this country, join a terrorist organization that wants to commit mass violence against your fellow citizens –you’re forfeiting your own citizenship.”

Listen to the entire clip here:

Who are the real losers in Canada’s election?

Yes, the far left, pro-Islam, socialist pretty boy, Justin Trudeau, might have won the election but what did the people of Canada actually win? Or more accurately what are they going to lose? Ezra lays it out:

ISLAMOPANDERER TRUDEAU STORIES/VIDEOS:

canada-so-why-does-justin-trudeau-seem-to-spend-so-much-time-in-bed-with-radical-muslims

how-could-canadians-ever-vote-for-a-muslim-appeasing-sycophant-like-justin-trudeau

justin-trudeau-left-wing-loon-condemns-quebecs-proposed-ban-on-all-religious-symbols

canada-justin-trudeau-leftist-useful-idiot-for-terror-linked-muslim-organizations

canada-left-wing-justin-trudeau-keeps-hopping-into-bed-with-radical-islamist-terrorism-supporters

canada-justin-trudeau-is-pandering-to-islamic-terrorist-supporters