| War on Terror | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: Aftermath of the September 11 attacks; American infantry in Afghanistan; an American soldier and Afghan interpreter in Zabul Province, Afghanistan; explosion of an Iraqi car bomb in Baghdad. |

|

| Belligerents | |

| Main participants: Other countries: (* note: most contributing nations are included in the international operations) |

Main targets:

|

| Commanders and leaders | |

(President 2001–2009) (President 2009–2017) (President 2017–present) (Prime Minister 1997–2007) (Prime Minister 2007–2010) (Prime Minister 2010–2016) (Prime Minister 2016–present) (President 2000–2008, 2012–present) (President 2008–2012) (President 2001–2003) (President 2003–2013) (President 2013–present) |

al-Qaeda

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

Taliban

Tehrik-i-Taliban

Haqqani Network

East Turkestan Islamic Movement

|

The War on Terror (WoT), also known as the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), is a metaphor of war referring to the international military campaign that started after the September 11th attacks on the United States.[47] U.S. PresidentGeorge W. Bush first used the term “War on Terror” on 20 September 2001.[47] The Bush administration and the Western media have since used the term to argue a global military, political, legal, and conceptual struggle against both terrorist organizations and against the regimes accused of supporting them. It was originally used with a particular focus on countries associated with Islamic terrorist organizations including al-Qaeda and like-minded organizations.

In 2013, President Barack Obama announced that the United States was no longer pursuing a War on Terror, as the military focus should be on specific enemies rather than a tactic. He stated, “We must define our effort not as a boundless ‘Global War on Terror,’ but rather as a series of persistent, targeted efforts to dismantle specific networks of violent extremists that threaten America.”[48]

In 2017 Donald Trump assumed presidency of the United States and vowed that the fight against ISIL is his number one priority.[49][50] A series of airstrikes were carried out at an ISIL stronghold in Syria in March 2017 and the Trump Administration announced the sending of more troops to ISIL-held territories in the Middle East to continue the fight against the terrorist organization.[51][52][53] Trump has also agreed to work together and carry joint operations with Russian President Vladimir Putin in the ongoing war on terror.[54]

Contents

[hide]

- 1Etymology

- 2Background

- 3U.S. objectives

- 4Afghanistan

- 5Iraq and Syria

- 6Pakistan

- 7Trans-Sahara (Northern Africa)

- 8Horn of Africa and the Red Sea

- 9Philippines

- 10Yemen

- 11U.S. Allies in the Middle East

- 12Libya

- 13Other military operations

- 14International military support

- 15Terrorist attacks and failed plots since 9/11

- 16Post 9/11 events inside the United States

- 17Casualties

- 18Costs

- 19Criticism

- 20Other Wars on Terror

- 21See also

- 22Notes

- 23References

- 24Further reading

- 25External links

Etymology[edit source]

The phrase “War on Terror” has been used to specifically refer to the ongoing military campaign led by the U.S., UK and their allies against organizations and regimes identified by them as terrorist, and usually excludes other independent counter-terrorist operations and campaigns such as those by Russia and India. The conflict has also been referred to by names other than the War on Terror. It has also been known as:

- World War III[55]

- World War IV[56] (assuming the Cold War was World War III)

- Bush’s War on Terror[57]

- The Long War[58][59]

- The Global War on Terror[60]

- The War Against al-Qaeda[61]

History of the name[edit source]

In 1984, the Reagan Administration used the term “war against terrorism” as part of an effort to pass legislation that was designed to freeze assets of terrorist groups and marshal the forces of government against them. Author Shane Harris asserts this was a reaction to the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing, which killed 241 U.S. and 58 French peacekeepers.[62]

The concept of America at war with terrorism may have begun on 11 September 2001 when Tom Brokaw, having just witnessed the collapse of one of the towers of the World Trade Center, declared “Terrorists have declared war on [America].”[63]

On 16 September 2001, at Camp David, President George W. Bush used the phrase war on terrorism in an unscripted and controversial comment when he said, “This crusade – this war on terrorism – is going to take a while, … “[64] Bush later apologized for this remark due to the negative connotations the term crusade has to people, e.g. of the Muslim faith. The word crusade was not used again.[65] On 20 September 2001, during a televised address to a joint session of Congress, Bush stated that “(o)ur ‘war on terror’ begins with al-Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated.”[66]

In April 2007, the British government announced publicly that it was abandoning the use of the phrase “War on Terror” as they found it to be less than helpful.[67] This was explained more recently by Lady Eliza Manningham-Buller. In her 2011 Reith lecture, the former head of MI5 said that the 9/11 attacks were “a crime, not an act of war. So I never felt it helpful to refer to a war on terror.”[68]

U.S. President Barack Obama has rarely used the term, but in his inaugural address on 20 January 2009, he stated: “Our nation is at war, against a far-reaching network of violence and hatred.”[69] In March 2009 the Defense Department officially changed the name of operations from “Global War on Terror” to “Overseas Contingency Operation” (OCO).[70] In March 2009, the Obama administration requested that Pentagon staff members avoid the use of the term and instead to use “Overseas Contingency Operation”.[70] Basic objectives of the Bush administration “war on terror”, such as targeting al Qaeda and building international counterterrorism alliances, remain in place.[71][72] In December 2012, Jeh Johnson, the General Counsel of the Department of Defense, stated that the military fight would be replaced by a law enforcement operation when speaking at Oxford University,[73] predicting that al Qaeda will be so weakened to be ineffective, and has been “effectively destroyed”, and thus the conflict will not be an armed conflict under international law.[74] In May 2013, Obama stated that the goal is “to dismantle specific networks of violent extremists that threaten America”;[75] which coincided with the U.S. Office of Management and Budget having changed the wording from “Overseas Contingency Operations” to “Countering Violent Extremism” in 2010.[76]

The rhetorical war on terror[edit source]

Because the actions involved in the “war on terrorism” are diffuse, and the criteria for inclusion are unclear. Political theorist Richard Jackson has argued that “the ‘war on terrorism’ therefore, is simultaneously a set of actual practices—wars, covert operations, agencies, and institutions—and an accompanying series of assumptions, beliefs, justifications, and narratives—it is an entire language or discourse.”[77] Jackson cites among many examples a statement by John Ashcroft that “the attacks of September 11 drew a bright line of demarcation between the civil and the savage”.[78]Administration officials also described “terrorists” as hateful, treacherous, barbarous, mad, twisted, perverted, without faith, parasitical, inhuman, and, most commonly, evil.[79] Americans, in contrast, were described as brave, loving, generous, strong, resourceful, heroic, and respectful of human rights.[80]

Both the term and the policies it denotes have been a source of ongoing controversy, as critics argue it has been used to justify unilateral preventive war, human rights abuses and other violations of international law.[81][82]

Background[edit source]

Precursor to the 11 September attacks[edit source]

The origins of al-Qaeda can be traced to the Soviet war in Afghanistan (December 1979 – February 1989). The United States, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and the People’s Republic of China supported the Islamist Afghan mujahadeen guerillas against the military forces of the Soviet Union and the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. A small number of “Afghan Arab” volunteers joined the fight against the Soviets, including Osama bin Laden, but there is no evidence they received any external assistance.[83] In May 1996 the group World Islamic Front for Jihad Against Jews and Crusaders (WIFJAJC), sponsored by bin Laden (and later re-formed as al-Qaeda), started forming a large base of operations in Afghanistan, where the Islamist extremist regime of the Taliban had seized power earlier in the year.[84] In February 1998, Osama bin Laden signed a fatwā, as head of al-Qaeda, declaring war on the West and Israel,[85][86] later in May of that same year al-Qaeda released a video declaring war on the U.S. and the West.[87][88]

On 7 August 1998, al-Qaeda struck the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, killing 224 people, including 12 Americans.[89] In retaliation, U.S. President Bill Clinton launched Operation Infinite Reach, a bombing campaign in Sudan and Afghanistan against targets the U.S. asserted were associated with WIFJAJC,[90][91] although others have questioned whether a pharmaceutical plant in Sudan was used as a chemical warfare facility. The plant produced much of the region’s antimalarial drugs[92] and around 50% of Sudan’s pharmaceutical needs.[93] The strikes failed to kill any leaders of WIFJAJC or the Taliban.[92]

Next came the 2000 millennium attack plots, which included an attempted bombing of Los Angeles International Airport. On 12 October 2000, the USS Cole bombing occurred near the port of Yemen, and 17 U.S. Navy sailors were killed.[94]

September 11, 2001, attacks[edit source]

On the morning of September 11, 2001, 19 men affiliated with al-Qaeda hijacked four airliners all bound for California. Once the hijackers assumed control of the airliners, they told the passengers that they had a bomb on board and would spare the lives of passengers and crew once their demands were met – no passenger and crew actually suspected that they would use the airliners as suicide weapons since it had never happened before in history, and many previous hijacking attempts had been resolved with the passengers and crew escaping unharmed after obeying the hijackers.[95][96] The hijackers – members of al-Qaeda’s Hamburg cell –[97] intentionally crashed two airliners into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City. Both buildings collapsed within two hours from fire damage related to the crashes, destroying nearby buildings and damaging others. The hijackers crashed a third airliner into the Pentagon in Arlington County, Virginia, just outside Washington D.C. The fourth plane crashed into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, after some of its passengers and flight crew attempted to retake control of the plane, which the hijackers had redirected toward Washington D.C., to target the White House or the U.S. Capitol. None of the flights had any survivors. A total of 2,977 victims and the 19 hijackers perished in the attacks.[98]

U.S. objectives[edit source]

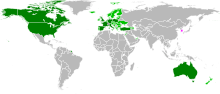

![]() Major terrorist attacks by al-Qaeda and affiliated groups: 1.1998 United States embassy bombings • 2. 11 September attacks 2001 • 3. Bali bombings 2002• 4. Madrid bombings 2004 • 5. London bombings 2005 • 6. Mumbai attacks 2008

Major terrorist attacks by al-Qaeda and affiliated groups: 1.1998 United States embassy bombings • 2. 11 September attacks 2001 • 3. Bali bombings 2002• 4. Madrid bombings 2004 • 5. London bombings 2005 • 6. Mumbai attacks 2008

The Authorization for the use of Military Force Against Terrorists or “AUMF” was made law on 14 September 2001, to authorize the use of United States Armed Forces against those responsible for the attacks on 11 September 2001. It authorized the President to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on 11 September 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or individuals. Congress declares this is intended to constitute specific statutory authorization within the meaning of section 5(b) of the War Powers Resolution of 1973.

The George W. Bush administration defined the following objectives in the War on Terror:[99]

- Defeat terrorists such as Osama bin Laden, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and demolish their organizations

- Identify, locate and demolish terrorists along with their organizations

- Deny sponsorship, support and sanctuary to terrorists

- End the state sponsorship of terrorism

- Establish and maintain an international standard of accountability concerning combating terrorism

- Strengthen and sustain the international effort to combat terrorism

- Work with willing and able states

- Enable weak states

- Persuade reluctant states

- Compel unwilling states

- Interdict and disorder Material support for terrorists

- Abolish terrorist sanctuaries and havens

- Diminish the underlying conditions that terrorists seek to exploit

- Partner with the international community to strengthen weak states and prevent (re)emergence of terrorism

- Win the war of ideals

- Defend U.S. citizens and interests at home and abroad

- Integrate the National Strategy for Homeland Security

- Attain domain awareness

- Enhance measures to ensure the integrity, reliability, and availability of critical, physical, and information-based infrastructures at home and abroad

- Implement measures to protect U.S. citizens abroad

- Ensure an integrated incident management capability

Afghanistan[edit source]

U.S. Army soldier of the 10th Mountain Division in Nuristan Province, June 2007

Operation Enduring Freedom[edit source]

Campaign streamer awarded to units who have participated in Operation Enduring Freedom

Operation Enduring Freedom is the official name used by the Bush administration for the War in Afghanistan, together with three smaller military actions, under the umbrella of the Global War on Terror. These global operations are intended to seek out and destroy any al-Qaeda fighters or affiliates.

Operation Enduring Freedom – Afghanistan[edit source]

On 20 September 2001, in the wake of the 11 September attacks, George W. Bush delivered an ultimatum to the Taliban government of Afghanistan, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, to turn over Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda leaders operating in the country or face attack.[66] The Taliban demanded evidence of bin Laden’s link to the 11 September attacks and, if such evidence warranted a trial, they offered to handle such a trial in an Islamic Court.[100] The U.S. refused to provide any evidence.

Subsequently, in October 2001, U.S. forces (with UK and coalition allies) invaded Afghanistan to oust the Taliban regime. On 7 October 2001, the official invasion began with British and U.S. forces conducting airstrike campaigns over enemy targets. Kabul, the capital city of Afghanistan, fell by mid-November. The remaining al-Qaeda and Taliban remnants fell back to the rugged mountains of eastern Afghanistan, mainly Tora Bora. In December, Coalition forces (the U.S. and its allies) fought within that region. It is believed that Osama bin Laden escaped into Pakistan during the battle.[101][102]

In March 2002, the U.S. and other NATO and non-NATO forces launched Operation Anaconda with the goal of destroying any remaining al-Qaeda and Taliban forces in the Shah-i-Kot Valley and Arma Mountains of Afghanistan. The Taliban suffered heavy casualties and evacuated the region.[103]

The Taliban regrouped in western Pakistan and began to unleash an insurgent-style offensive against Coalition forces in late 2002.[104] Throughout southern and eastern Afghanistan, firefights broke out between the surging Taliban and Coalition forces. Coalition forces responded with a series of military offensives and an increase of troops in Afghanistan. In February 2010, Coalition forces launched Operation Moshtarak in southern Afghanistan along with other military offensives in the hopes that they would destroy the Taliban insurgency once and for all.[105] Peace talks are also underway between Taliban affiliated fighters and Coalition forces.[106] In September 2014, Afghanistan and the United States signed a security agreement, which permits the United States and NATO forces to remain in Afghanistan until at least 2024.[107] The United States and other NATO and non-NATO forces are planning to withdraw;[108] with the Taliban claiming it has defeated the United States and NATO,[109] and the Obama Administration viewing it as a victory.[110] In December 2014, ISAF encasing its colors, and Resolute Support began as the NATO operation in Afghanistan.[111]Continued United States operations within Afghanistan will continue under the name “Operation Freedom’s Sentinel”.[112]

International Security Assistance Force[edit source]

December 2001 saw the creation of the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to assist the Afghan Transitional Administration and the first post-Taliban elected government. With a renewed Taliban insurgency, it was announced in 2006 that ISAF would replace the U.S. troops in the province as part of Operation Enduring Freedom.

The British 16th Air Assault Brigade (later reinforced by Royal Marines) formed the core of the force in southern Afghanistan, along with troops and helicopters from Australia, Canada and the Netherlands. The initial force consisted of roughly 3,300 British, 2,000 Canadian, 1,400 from the Netherlands and 240 from Australia, along with special forces from Denmark and Estonia and small contingents from other nations. The monthly supply of cargo containers through Pakistani route to ISAF in Afghanistan is over 4,000 costing around 12 billion in Pakistani Rupees.[113][114][115][116][117]

Iraq and Syria[edit source]

A British C-130J Hercules aircraft launches flare countermeasures before being the first coalition aircraft to land on the newly reopened military runway at Baghdad International Airport

Iraq had been listed as a State sponsor of terrorism by the U.S. since 1990,[118] when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. Iraq had also been on the list from 1979 to 1982; it was removed so that the U.S. could provide material support to Iraq in its war with Iran. Hussein’s regime had proven to be a problem for the UN and Iraq’s neighbors due to its use of chemical weapons against Iranians and Kurds in the 1980s.

Iraqi no-fly zones[edit source]

Following the ceasefire agreement that suspended hostilities (but not officially ended) in the 1991 Gulf War, the United States and its allies instituted and began patrolling Iraqi no-fly zones, to protect Iraq’s Kurdish and Shi’a Arab population—both of which suffered attacks from the Hussein regime before and after the Gulf War—in Iraq’s northern and southern regions, respectively. U.S. forces continued in combat zone deployments through November 1995 and launched Operation Desert Fox against Iraq in 1998 after it failed to meet U.S. demands for “unconditional cooperation” in weapons inspections.[119]

In the aftermath of Operation Desert Fox, during December 1998, Iraq announced that it would no longer respect the no-fly zones and resumed its attempts to shoot down U.S. aircraft.

Operation Iraqi Freedom[edit source]

The Iraq War began in March 2003 with an air campaign, which was immediately followed by a U.S.-led ground invasion. The Bush administration stated the invasion was the “serious consequences” spoken of in the UNSC Resolution 1441, partially by Iraq possessing weapons of mass destruction. The Bush administration also stated the Iraq war was part of the War on Terror; something later questioned or contested.

The first ground attack came at the Battle of Umm Qasr on 21 March 2003 when a combined force of British, American and Polish forces seized control of the port city of Umm Qasr.[120] Baghdad, Iraq’s capital city, fell to American troops in April 2003 and Saddam Hussein’s government quickly dissolved.[121] On 1 May 2003, Bush announced that major combat operations in Iraq had ended.[122] However, an insurgency arose against the U.S.-led coalition and the newly developing Iraqi military and post-Saddam government. The rebellion, which included al-Qaeda-affiliated groups, led to far more coalition casualties than the invasion. Other elements of the insurgency were led by fugitive members of President Hussein’s Ba’ath regime, which included Iraqi nationalists and pan-Arabists. Many insurgency leaders are Islamists and claim to be fighting a religious war to reestablish the Islamic Caliphate of centuries past.[123] Iraqi President Saddam Hussein was captured by U.S. forces in December 2003. He was executed in 2006.

In 2004, the insurgent forces grew stronger. The U.S. conducted attacks on insurgent strongholds in cities like Najaf and Fallujah.

In January 2007, President Bush presented a new strategy for Operation Iraqi Freedom based upon counter-insurgency theories and tactics developed by General David Petraeus. The Iraq War troop surge of 2007 was part of this “new way forward” and, along with U.S. backing of Sunni groups it had previously sought to defeat, has been credited with a widely recognized dramatic decrease in violence by up to 80%.

Operation New Dawn[edit source]

The war entered a new phase on 1 September 2010,[124] with the official end of U.S. combat operations. The last U.S. troops exited Iraq on 18 December 2011.[125]

Operation Inherent Resolve (Syria and Iraq)[edit source]

Tomahawk missiles being fired from USS Philippine Sea and USS Arleigh Burke at IS targets in Syria

In a major split in the ranks of Al Qaeda’s organization, the Iraqi franchise, known as Al Qaeda in Iraq covertly invaded Syria and the Levant and began participating in the ongoing Syrian Civil War, gaining enough support and strength to re-invade Iraq’s western provinces under the name of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS/ISIL), taking over much of the country in a blitzkrieg-like action and combining the Iraq insurgency and Syrian Civil War into a single conflict.[126] Due to their extreme brutality and a complete change in their overall ideology, Al Qaeda’s core organization in Central Asia eventually denounced ISIS and directed their affiliates to cut off all ties with this organization.[127] Many analysts[who?] believe that because of this schism, Al Qaeda and ISIL are now in a competition to retain the title of the world’s most powerful terrorist organization.[128]

The Obama administration began to re-engage in Iraq with a series of airstrikes aimed at ISIS starting on 10 August 2014.[129] On 9 September 2014, President Obama said that he had the authority he needed to take action to destroy the militant group known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, citing the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force Against Terrorists, and thus did not require additional approval from Congress.[130] The following day on 10 September 2014 President Barack Obama made a televised speech about ISIL, which he stated: “Our objective is clear: We will degrade, and ultimately destroy, ISIL through a comprehensive and sustained counter-terrorism strategy”.[131] Obama has authorized the deployment of additional U.S. Forces into Iraq, as well as authorizing direct military operations against ISIL within Syria.[131]On the night of 21/22 September the United States, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the UAE, Jordan and Qatar started air attacks against ISIS in Syria.[citation needed]

In October 2014, it was reported that the U.S. Department of Defense considers military operations against ISIL as being under Operation Enduring Freedom in regards to campaign medal awarding.[132] On 15 October, the military intervention became known as “Operation Inherent Resolve”.[133]

Pakistan[edit source]

Following the 11 September 2001 attacks, former President of Pakistan Pervez Musharraf sided with the U.S. against the Taliban government in Afghanistan after an ultimatum by then U.S. President George W. Bush. Musharraf agreed to give the U.S. the use of three airbases for Operation Enduring Freedom. United States Secretary of State Colin Powell and other U.S. administration officials met with Musharraf. On 19 September 2001, Musharraf addressed the people of Pakistan and stated that, while he opposed military tactics against the Taliban, Pakistan risked being endangered by an alliance of India and the U.S. if it did not cooperate. In 2006, Musharraf testified that this stance was pressured by threats from the U.S., and revealed in his memoirs that he had “war-gamed” the United States as an adversary and decided that it would end in a loss for Pakistan.[134]

On 12 January 2002, Musharraf gave a speech against Islamic extremism. He unequivocally condemned all acts of terrorism and pledged to combat Islamic extremism and lawlessness within Pakistan itself. He stated that his government was committed to rooting out extremism and made it clear that the banned militant organizations would not be allowed to resurface under any new name. He said, “the recent decision to ban extremist groups promoting militancy was taken in the national interest after thorough consultations. It was not taken under any foreign influence”.[135]

In 2002, the Musharraf-led government took a firm stand against the jihadi organizations and groups promoting extremism, and arrested Maulana Masood Azhar, head of the Jaish-e-Mohammed, and Hafiz Muhammad Saeed, chief of the Lashkar-e-Taiba, and took dozens of activists into custody. An official ban was imposed on the groups on 12 January.[136] Later that year, the Saudi born Zayn al-Abidn Muhammed Hasayn Abu Zubaydah was arrested by Pakistani officials during a series of joint U.S.-Pakistan raids. Zubaydah is said to have been a high-ranking al-Qaeda official with the title of operations chief and in charge of running al-Qaeda training camps.[137] Other prominent al-Qaeda members were arrested in the following two years, namely Ramzi bin al-Shibh, who is known to have been a financial backer of al-Qaeda operations, and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who at the time of his capture was the third highest-ranking official in al-Qaeda and had been directly in charge of the planning for the 11 September attacks.

In 2004, the Pakistan Army launched a campaign in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan’s Waziristan region, sending in 80,000 troops. The goal of the conflict was to remove the al-Qaeda and Taliban forces in the area.

After the fall of the Taliban regime, many members of the Taliban resistance fled to the Northern border region of Afghanistan and Pakistan where the Pakistani army had previously little control. With the logistics and air support of the United States, the Pakistani Army captured or killed numerous al-Qaeda operatives such as Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, wanted for his involvement in the USS Cole bombing, the Bojinka plot, and the killing of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl.

The United States has carried out a campaign of Drone attacks on targets all over the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. However, the Pakistani Taliban still operates there. To this day it is estimated that 15 U.S. soldiers were killed while fighting al-Qaeda and Taliban remnants in Pakistan since the War on Terror began.[138]

Osama bin Laden, who was of many founders of al-Qaeda, his wife, and son, were all killed on 2 May 2011, during a raid conducted by the United States special operations forces in Abbottabad, Pakistan.[139]

The use of drones by the Central Intelligence Agency in Pakistan to carry out operations associated with the Global War on Terror sparks debate over sovereignty and the laws of war. The U.S. Government uses the CIA rather than the U.S. Air Force for strikes in Pakistan to avoid breaching sovereignty through military invasion. The United States was criticized by[according to whom?] a report on drone warfare and aerial sovereignty for abusing the term ‘Global War on Terror’ to carry out military operations through government agencies without formally declaring war.

In the three years before the attacks of 11 September, Pakistan received approximately US$9 million in American military aid. In the three years after, the number increased to US$4.2 billion, making it the country with the maximum funding post 9/11.

Baluchistan[edit source]

Brahamdagh Bugti stated in a 2008 interview that he would accept aid from India, Afghanistan, and Iran in defending Baluchistan.[140] Pakistan has repeatedly accused India of supporting Baloch rebels,[141][142] and Wright-Neville writes that outside Pakistan, some Western observers also believe that India secretly funds the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA).[143]

The uprising in Baluchistan started after Pakistan invaded and occupied the territory in 1948. Various NGOs have reported human rights violations in committed by Pakistani armed forces. According to reports, approximately 18,000 Baluch residents are reportedly missing and about 2000 have been killed.[144]

Trans-Sahara (Northern Africa)[edit source]

Operation Enduring Freedom – Trans Sahara[edit source]

Operation Enduring Freedom – Trans Sahara (OEF-TS) is the name of the military operation conducted by the U.S. and partner nations in the Sahara/Sahel region of Africa, consisting of counter-terrorism efforts and policing of arms and drug trafficking across central Africa.

The conflict in northern Mali began in January 2012 with radical Islamists (affiliated to al-Qaeda) advancing into northern Mali. The Malian government had a hard time maintaining full control over their country. The fledgling government requested support from the international community on combating the Islamic militants. In January 2013, France intervened on behalf of the Malian government’s request and deployed troops into the region. They launched Operation Serval on 11 January 2013, with the hopes of dislodging the al-Qaeda affiliated groups from northern Mali.[145]

Horn of Africa and the Red Sea[edit source]

Operation Enduring Freedom – Horn of Africa[edit source]

This extension of Operation Enduring Freedom was titled OEF-HOA. Unlike other operations contained in Operation Enduring Freedom, OEF-HOA does not have a specific organization as a target. OEF-HOA instead focuses its efforts to disrupt and detect militant activities in the region and to work with willing governments to prevent the reemergence of militant cells and activities.[146]

In October 2002, the Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) was established in Djibouti at Camp Lemonnier.[147] It contains approximately 2,000 personnel including U.S. military and special operations forces (SOF) and coalition force members, Combined Task Force 150 (CTF-150).

Task Force 150 consists of ships from a shifting group of nations, including Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Pakistan, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. The primary goal of the coalition forces is to monitor, inspect, board and stop suspected shipments from entering the Horn of Africa region and affecting the United States’ Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Included in the operation is the training of selected armed forces units of the countries of Djibouti, Kenya and Ethiopia in counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency tactics. Humanitarian efforts conducted by CJTF-HOA include rebuilding of schools and medical clinics and providing medical services to those countries whose forces are being trained.

The program expands as part of the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Initiative as CJTF personnel also assist in training the armed forces of Chad, Niger, Mauritania and Mali. However, the War on Terror does not include Sudan, where over 400,000 have died in an ongoing civil war.

On 1 July 2006, a Web-posted message purportedly written by Osama bin Laden urged Somalis to build an Islamic state in the country and warned western governments that the al-Qaeda network would fight against them if they intervened there.[148]

Somalia has been considered a “failed state” because its official central government was weak, dominated by warlords and unable to exert effective control over the country. Beginning in mid-2006, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), an Islamist faction campaigning on a restoration of “law and order” through Sharia law, had rapidly taken control of much of southern Somalia.

On 14 December 2006, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Jendayi Frazer claimed al-Qaeda cell operatives were controlling the Islamic Courts Union, a claim denied by the ICU.[149]

By late 2006, the UN-backed Transitional Federal Government (TFG) of Somalia had seen its power effectively limited to Baidoa, while the Islamic Courts Union controlled the majority of southern Somalia, including the capital of Mogadishu. On 20 December 2006, the Islamic Courts Union launched an offensive on the government stronghold of Baidoa and saw early gains before Ethiopia intervened for the government.

By 26 December, the Islamic Courts Union retreated towards Mogadishu, before again retreating as TFG/Ethiopian troops neared, leaving them to take Mogadishu with no resistance. The ICU then fled to Kismayo, where they fought Ethiopian/TFG forces in the Battle of Jilib.

The Prime Minister of Somalia claimed that three “terror suspects” from the 1998 United States embassy bombings are being sheltered in Kismayo.[150] On 30 December 2006, al-Qaeda deputy leader Ayman al-Zawahiri called upon Muslims worldwide to fight against Ethiopia and the TFG in Somalia.[151]

On 8 January 2007, the U.S. launched the Battle of Ras Kamboni by bombing Ras Kamboni using AC-130 gunships.[152]

On 14 September 2009, U.S. Special Forces killed two men and wounded and captured two others near the Somali village of Baarawe. Witnesses claim that helicopters used for the operation launched from French-flagged warships, but that could not be confirmed. A Somali-based al-Qaida affiliated group, the Al-Shabaab, has verified the death of “sheik commander” Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan along with an unspecified number of militants.[153] Nabhan, a Kenyan, was wanted in connection with the 2002 Mombasa attacks.[154]

Philippines[edit source]

Operation Enduring Freedom – Philippines[edit source]

U.S. Special Forces soldier and infantrymen of the Philippine Army

In January 2002, the United States Special Operations Command, Pacific deployed to the Philippines to advise and assist the Armed Forces of the Philippines in combating Filipino Islamist groups.[155] The operations were mainly focused on removing the Abu Sayyaf group and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) from their stronghold on the island of Basilan.[156] The second portion of the operation was conducted as a humanitarian program called “Operation Smiles”. The goal of the program was to provide medical care and services to the region of Basilan as part of a “Hearts and Minds” program.[157][158] Joint Special Operations Task Force – Philippines disbanded in June 2014,[159]ending a successful 12-year mission.[160] After JSOTF-P had disbanded, as late as November 2014, American forces continued to operate in the Philippines under the name “PACOM Augmentation Team”, until February 24, 2015.[161][162]

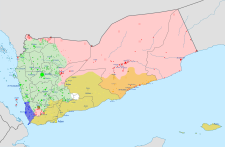

Yemen[edit source]

The United States has also conducted a series of military strikes on al-Qaeda militants in Yemen since the War on Terror began.[163] Yemen has a weak central government and a powerful tribal system that leaves large lawless areas open for militant training and operations. Al-Qaeda has a strong presence in the country.[164] On 31 March 2011, AQAP declared the Al-Qaeda Emirate in Yemen after its captured most of Abyan Governorate.[165]

The U.S., in an effort to support Yemeni counter-terrorism efforts, has increased their military aid package to Yemen from less than $11 million in 2006 to more than $70 million in 2009, as well as providing up to $121 million for development over the next three years.[166]

U.S. Allies in the Middle East[edit source]

Israel[edit source]

Israel has been fighting terrorist groups such Hezbollah, Hamas, and Islamic Jihad, who are all Iran’s proxies aimed at Iran’s objective to destroy Israel. According to the Clarion Project: “Since 1979, Iran has been responsible for countless terrorist plots, directly through regime agents or indirectly through proxies like Hamas and Hezbollah.[167] In 2006, U.S. President [George W Bush] said that Israel’s war on terrorist group Hezbollah was part of war on terror.[168]

Saudi Arabia[edit source]

Saudi Arabia witnessed multiple terror attacks from different groups such as Al-Queda whos leader Osama Bin Laden delcared war on the Saudi government. On June 16, 1996, the Khobar Towers bombing took place in Saudi Arabia that killed 19 U.S. soldiers. It is widely thought that Iran orchestrated it. The 9/11 Commission concluded that Hezbollah, likely with the support of the Iranian regime, was the perpetrator. It said there are “signs” that Al-Qaeda also played a role.[167]

Libya[edit source]

On 19 March 2011, a multi-state coalition began a military action in Libya, ostensibly to implement United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973. The United Nations Intent and Voting was to have “an immediate ceasefire in Libya, including an end to the current attacks against civilians, which it said might constitute crimes against humanity” … “imposing a ban on all flights in the country’s airspace – a no-fly zone – and tightened sanctions on the Qadhafi regime and its supporters.” The resolution was taken in response to events during the Libyan Civil War,[169] and military operations began, with American and British naval forces firing over 110 Tomahawk cruise missiles,[170] the French Air Force, British Royal Air Force, and Royal Canadian Air Force[171] undertaking sorties across Libya and a naval blockade by Coalition forces.[172] French jets launched air strikes against Libyan Army tanks and vehicles.[173][174] The Libyan government response to the campaign was totally ineffectual, with Gaddafi’s forces not managing to shoot down a single NATO plane despite the country possessing 30 heavy SAM batteries, 17 medium SAM batteries, 55 light SAM batteries (a total of 400-450 launchers, including 130-150 SA-6 launchers and some SA-8 launchers), and 440-600 short-range air-defense guns.[175][176] The official names for the interventions by the coalition members are Opération Harmattan by France; Operation Ellamy by the United Kingdom; Operation Mobile for the Canadian participation and Operation Odyssey Dawn for the United States.[177]

From the beginning of the intervention, the initial coalition of Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Norway, Qatar, Spain, UK and US[178][179][180][181][182] expanded to nineteen states, with newer states mostly enforcing the no-fly zone and naval blockade or providing military logistical assistance. The effort was initially largely led by France and the United Kingdom, with command shared with the United States. NATO took control of the arms embargo on 23 March, named Operation Unified Protector. An attempt to unify the military leadership of the air campaign (while keeping political and strategic control with a small group), first failed over objections by the French, German, and Turkish governments.[183][184] On 24 March, NATO agreed to take control of the no-fly zone, while command of targeting ground units remains with coalition forces.[185][186][187] The handover occurred on 31 March 2011 at 06:00 UTC (08:00 local time). NATO flew 26,500 sorties since it took charge of the Libya mission on 31 March 2011.

Fighting in Libya ended in late October following the death of Muammar Gaddafi, and NATO stated it would end operations over Libya on 31 October 2011. Libya’s new government requested its mission to be extended to the end of the year,[188] but on 27 October, the Security Council voted to end NATO’s mandate for military action on 31 October.[189]

An AV-8B Harrier takes off from the flight deck of the USS Wasp during Operation Odyssey Lightning, August 8, 2016.

NBC News reported that in mid-2014, ISIS had about 1,000 fighters in Libya. Taking advantage of a power vacuum in the center of the country, far from the major cities of Tripoli and Benghazi, ISIS expanded rapidly over the next 18 months. Local militants were joined by jihadists from the rest of North Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the Caucasus. The force absorbed or defeated other Islamist groups inside Libya and the central ISIS leadership in Raqqa, Syria, began urging foreign recruits to head for Libya instead of Syria. ISIS seized control of the coastal city of Sirte in early 2015 and then began to expand to the east and south. By the beginning of 2016, it had effective control of 120 to 150 miles of coastline and portions of the interior and had reached Eastern Libya’s major population center, Benghazi. In spring 2016, AFRICOM estimated that ISIS had about 5,000 fighters in its stronghold of Sirte.[190]

However, the indigenous rebel groups who had staked their claims to Libya and turned their weapons on ISIS — with the help of airstrikes by Western forces, including U.S. drones, the Libyan population resented the outsiders who wanted to establish a fundamentalist regime on their soil. Militias loyal to the new Libyan unity government, plus a separate and rival force loyal to a former officer in the Qaddafi regime, launched an assault on ISIS outposts in Sirte and the surrounding areas that lasted for months. According to U.S. military estimates, ISIS ranks shrank to somewhere between a few hundred and 2,000 fighters. In August 2016, the U.S. military began airstrikes that, along with continued pressure on the ground from the Libyan militias, pushed the remaining ISIS fighters back into Sirte, In all, U.S. drones and planes hit ISIS nearly 590 times, the Libyan militias reclaimed the city in mid-December.[190] On January 18, 2017, ABC News reported that two USAF B-2 bombers struck two ISIS camps 28 miles south of Sirte, the airstrikes targeted between 80 and 100 ISIS fighters in multiple camps, an unmanned aircraft also participated in the airstrikes. NBC News reported that as many as 90 ISIS fighters were killed in the strike, a U.S. defense official said that “This was the largest remaining ISIS presence in Libya,” and that “They have been largely marginalized, but I am hesitant to say they have been eliminated in Libya.”[190]

Other military operations[edit source]

Operation Active Endeavour[edit source]

Operation Active Endeavour is a naval operation of NATO started in October 2001 in response to the 11 September attacks. It operates in the Mediterranean and is designed to prevent the movement of militants or weapons of mass destruction and to enhance the security of shipping in general.[191]

Fighting in Kashmir[edit source]

In a ‘Letter to American People’ written by Osama bin Laden in 2002, he stated that one of the reasons he was fighting America is because of its support of India on the Kashmir issue.[192][193] While on a trip to Delhi in 2002, U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld suggested that Al-Qaeda was active in Kashmir, though he did not have any hard evidence.[194][195] In 2002, The Christian Science Monitor published an article claiming that Al-Qaeda and its affiliates were “thriving” in Pakistan-administered Kashmir with the tacit approval of Pakistan’s National Intelligence agency Inter-Services Intelligence.[196] A team of Special Air Service and Delta Force was sent into Indian-administered Kashmir in 2002 to hunt for Osama bin Laden after reports that he was being sheltered by the Kashmiri militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen.[197] U.S. officials believed that Al-Qaeda was helping organize a campaign of terror in Kashmir to provoke conflict between India and Pakistan. Fazlur Rehman Khalil, the leader of the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, signed al-Qaeda’s 1998 declaration of holy war, which called on Muslims to attack all Americans and their allies.[198] Indian sources claimed that In 2006, Al-Qaeda claimed they had established a wing in Kashmir; this worried the Indian government.[199] India also argued that Al-Qaeda has strong ties with the Kashmir militant groups Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed in Pakistan.[200] While on a visit to Pakistan in January 2010, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates stated that Al-Qaeda was seeking to destabilize the region and planning to provoke a nuclear war between India and Pakistan.[201]

In September 2009, a U.S. Drone strike reportedly killed Ilyas Kashmiri, who was the chief of Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami, a Kashmiri militant group associated with Al-Qaeda.[202][203] Kashmiri was described by Bruce Riedel as a ‘prominent’ Al-Qaeda member,[204] while others described him as the head of military operations for Al-Qaeda.[205] Waziristan had now become the new battlefield for Kashmiri militants, who were now fighting NATO in support of Al-Qaeda.[206] On 8 July 2012, Al-Badar Mujahideen, a breakaway faction of Kashmir centric terror group Hizbul Mujahideen, on the conclusion of their two-day Shuhada Conference called for a mobilization of resources for continuation of jihad in Kashmir.[207]

American military intervention in Cameroon[edit source]

In October 2015, the US began deploying 300 soldiers[208] to Cameroon, with the invitation of the Cameroonian government, to support African forces in a non-combat role in their fight against ISIS insurgency in that country. The troops’ primary missions will revolve around providing intelligence support to local forces as well as conducting reconnaissance flights.[209]

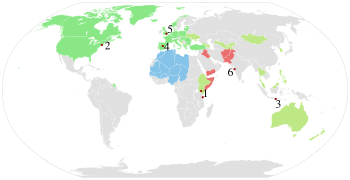

International military support[edit source]

The United Kingdom is the second largest contributor of troops in Afghanistan

The invasion of Afghanistan is seen to have been the first action of this war, and initially involved forces from the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Afghan Northern Alliance. Since the initial invasion period, these forces were augmented by troops and aircraft from Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand and Norway amongst others. In 2006, there were about 33,000 troops in Afghanistan.

On 12 September 2001, less than 24 hours after the 11 September attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C., NATO invoked Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty and declared the attacks to be an attack against all 19 NATO member countries. Australian Prime Minister John Howard also stated that Australia would invoke the ANZUS Treaty along similar lines.[210]

In the following months, NATO took a broad range of measures to respond to the threat of terrorism. On 22 November 2002, the member states of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) decided on a Partnership Action Plan against Terrorism, which explicitly states, “[The] EAPC States are committed to the protection and promotion of fundamental freedoms and human rights, as well as the rule of law, in combating terrorism.”[211] NATO started naval operations in the Mediterranean Sea designed to prevent the movement of terrorists or weapons of mass destruction as well as to enhance the security of shipping in general called Operation Active Endeavour.

Support for the U.S. cooled when America made clear its determination to invade Iraq in late 2002. Even so, many of the “coalition of the willing” countries that unconditionally supported the U.S.-led military action have sent troops to Afghanistan, particular neighboring Pakistan, which has disowned its earlier support for the Taliban and contributed tens of thousands of soldiers to the conflict. Pakistan was also engaged in the War in North-West Pakistan (Waziristan War). Supported by U.S. intelligence, Pakistan was attempting to remove the Taliban insurgency and al-Qaeda element from the northern tribal areas.[212]

Terrorist attacks and failed plots since 9/11[edit source]

| This section does not cite any sources. (August 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Al-Qaeda[edit source]

Since 9/11, Al-Qaeda and other affiliated radical Islamist groups have executed attacks in several parts of the world where conflicts are not taking place. Whereas countries like Pakistan have suffered hundreds of attacks killing tens of thousands and displacing much more.

- The 2002 Bali bombings in Indonesia were committed by various members of Jemaah Islamiyah, an organization linked to Al-Qaeda.

- The 2003 Casablanca bombings were carried out by Salafia Jihadia, an Al-Qaeda affiliate.

- After the 2003 Istanbul bombings, Turkey charged 74 people with involvement, including Syrian Al-Qaeda member Loai al-Saqa.

- The 2004 Madrid train bombings in Spain were “inspired by” Al-Qaeda, though no direct involvement has been established.

- The 7 July 2005 London bombings in the United Kingdom were perpetrated by four homegrown terrorists, one of whom appeared in an edited video with a known Al-Qaeda operative, though the British government denies Al-Qaeda involvement.

- Al Qaeda claimed responsibility for the 11 April 2007 Algiers bombings in Algeria.

- The 2007 Glasgow International Airport attack in the United Kingdom was carried out by a pair of bombers whose laptops and suicide notes included videos and speeches referencing Al-Qaeda, though no direct involvement was established.

- The 2009 Fort Hood shooting in the United States was committed by Nidal Malik Hasan, who had been in communication with Anwar al-Awlaki, though the Department of Defense classifies the shooting as an incidence of workplace violence.

- Morocco blames Al-Qaeda for the 2011 Marrakech bombing, though Al-Qaeda denies involvement.

- The 2012 Toulouse and Montauban shootings in France were committed by Mohammed Merah, who reportedly had familial ties to Al-Qaeda, along with a history of petty crime and psychological issues. Merah claimed ties to Al-Qaeda, though French authorities deny any connection.

- To date, no one has been convicted for the 2012 U.S. Consulate attack in Benghazi in Libya, and no one has claimed responsibility. Branches of Al-Qaeda, Al-Qaeda affiliates, and individuals “sympathetic to Al-Qaeda” are blamed.

- The gunmen in the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris identified themselves as belonging to Al-Qaeda’s branch in Yemen.

There may also have been several additional planned attacks that were not successful.

- 2004 financial buildings plot (The United States and the United Kingdom)

- 21 July 2005 London bombings (United Kingdom)

- 2006 Toronto terrorism plot (Canada)

- 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot involving liquid explosives carried onto commercial airplanes

- 2006 Hudson River bomb plot (United States)

- 2007 Fort Dix attack plot (United States)

- 2007 London car bombs (United Kingdom)

- 2007 John F. Kennedy International Airport attack plot (United States)

- 2009 Bronx terrorism plot (United States)

- 2009 New York City Subway and United Kingdom plot (The United States and the United Kingdom)

- 2009 Northwest Airlines Flight 253 bombing plot (United States)

- 2010 Stockholm bombings (Sweden)

- 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt (United States)

- 2010 cargo plane bomb plot (United States)

- 2010 Portland car bomb plot (United States)

- 2011 Manhattan terrorism plot (United States)

- 2013 VIA Rail Canada terrorism plot (Canada)

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)[edit source]

- 2013 Reyhanlı bombings in Turkey that led to 52 deaths and the injury of 140 people.

- 2014 Canadian parliament shootings, an ISIL-inspired attack on Canada’s Parliament, resulting in the passing of a Canadian soldier, as well as that of the perpetrator.

- 2015 Porte de Vincennes siege perpetrated by Amedy Coulibaly in Paris, which led to four deaths and the injury of nine others.

- 2015 Corinthia Hotel attack on 27 January in Libya that resulted in 10 deaths.

- 2015 Sana’a mosque bombings on 20 March that led to the death of 142 and injury of 351 people.

- 2015 Curtis Culwell Center attack on 3 May 2015 that resulted in the injury of one security officer.

- November 2015 Paris attacks on the 13th that left at least 132 dead and injured at least 352 civilians caused France to be put under a state of emergency, close its borders and deploy three French contingency plans.[213] Islamic State claimed responsibility for the attacks,[214] with French President François Hollande later stated the attacks were carried out “by the Islamic state with internal help”.[215]

- 2015 San Bernardino attack on 2 December 2015, two gunmen attacked a county building in San Bernardino, California killing 16 people and injuring 24 others.[216]

- 2016 Brussels bombing on 22 March 2016 two bombing attacks, first at Brussels Airport and the second at the Maalbeek/Maelbeek metro station, killed 35 people and injured more than 300.

- 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting on 12 June 2016 a gunman opened fire at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida killing 50 people and wounding 53 others. It is the worst terrorist attack on US soil since 11 September 2001 [217]

So far, there has been only one failed plot by ISIL:[citation needed]

- 2014 mass-beheading plot in Australia

Post 9/11 events inside the United States[edit source]

A U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement helicopter patrols the airspace over New York City

In addition to military efforts abroad, in the aftermath of 9/11, the Bush Administration increased domestic efforts to prevent future attacks. Various government bureaucracies that handled security and military functions were reorganized. A new cabinet-level agency called the United States Department of Homeland Security was created in November 2002 to lead and coordinate the largest reorganization of the U.S. federal government since the consolidation of the armed forces into the Department of Defense.[citation needed]

The Justice Department launched the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System for certain male non-citizens in the U.S., requiring them to register in person at offices of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

The USA PATRIOT Act of October 2001 dramatically reduces restrictions on law enforcement agencies’ ability to search telephone, e-mail communications, medical, financial, and other records; eases restrictions on foreign intelligence gathering within the United States; expands the Secretary of the Treasury‘s authority to regulate financial transactions, particularly those involving foreign individuals and entities; and broadens the discretion of law enforcement and immigration authorities in detaining and deporting immigrants suspected of terrorism-related acts. The act also expanded the definition of terrorism to include domestic terrorism, thus enlarging the number of activities to which the USA PATRIOT Act’s expanded law enforcement powers could be applied. A new Terrorist Finance Tracking Program monitored the movements of terrorists’ financial resources (discontinued after being revealed by The New York Times). Global telecommunication usage, including those with no links to terrorism,[218] is being collected and monitored through the NSA electronic surveillance program. The Patriot Act is still in effect.

Political interest groups have stated that these laws remove important restrictions on governmental authority, and are a dangerous encroachment on civil liberties, possible unconstitutional violations of the Fourth Amendment. On 30 July 2003, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed the first legal challenge against Section 215 of the Patriot Act, claiming that it allows the FBI to violate a citizen’s First Amendment rights, Fourth Amendment rights, and right to due process, by granting the government the right to search a person’s business, bookstore, and library records in a terrorist investigation, without disclosing to the individual that records were being searched.[219] Also, governing bodies in many communities have passed symbolic resolutions against the act.

John Walker Lindh was captured as an enemy combatant during the United States’ 2001 invasion of Afghanistan

In a speech on 9 June 2005, Bush said that the USA PATRIOT Act had been used to bring charges against more than 400 suspects, more than half of whom had been convicted. Meanwhile, the ACLU quoted Justice Department figures showing that 7,000 people have complained of abuse of the Act.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) began an initiative in early 2002 with the creation of the Total Information Awareness program, designed to promote information technologies that could be used in counter-terrorism. This program, facing criticism, has since been defunded by Congress.

By 2003, 12 major conventions and protocols were designed to combat terrorism. These were adopted and ratified by many states. These conventions require states to co-operate on principal issues regarding unlawful seizure of aircraft, the physical protection of nuclear materials, and the freezing of assets of militant networks.[220]

In 2005, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1624 concerning incitement to commit acts of terrorism and the obligations of countries to comply with international human rights laws.[221] Although both resolutions require mandatory annual reports on counter-terrorism activities by adopting nations, the United States and Israel have both declined to submit reports. In the same year, the United States Department of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a planning document, by the name “National Military Strategic Plan for the War on Terrorism”, which stated that it constituted the “comprehensive military plan to prosecute the Global War on Terror for the Armed Forces of the United States…including the findings and recommendations of the 9/11 Commission and a rigorous examination with the Department of Defense”.

On 9 January 2007, the House of Representatives passed a bill, by a vote of 299–128, enacting many of the recommendations of the 9/11 Commission The bill passed in the U.S. Senate,[222] by a vote of 60–38, on 13 March 2007 and it was signed into law on 3 August 2007 by President Bush. It became Public Law 110-53. In July 2012, U.S. Senate passed a resolution urging that the Haqqani Network be designated a foreign terrorist organization.[223]

The Office of Strategic Influence was secretly created after 9/11 for the purpose of coordinating propaganda efforts but was closed soon after being discovered. The Bush administration implemented the Continuity of Operations Plan (or Continuity of Government) to ensure that U.S. government would be able to continue in catastrophic circumstances.

Since 9/11, extremists made various attempts to attack the United States, with varying levels of organization and skill. For example, vigilant passengers aboard a transatlantic flight prevented Richard Reid, in 2001, and Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, in 2009, from detonating an explosive device.

Other terrorist plots have been stopped by federal agencies using new legal powers and investigative tools, sometimes in cooperation with foreign governments.[citation needed]

Such thwarted attacks include:

- The 2001 shoe bomb plot

- A plan to crash airplanes into the U.S. Bank Tower (aka Library Tower) in Los Angeles

- The 2003 plot by Iyman Faris to blow up the Brooklyn Bridge in New York City

- The 2004 Financial buildings plot, which targeted the International Monetary Fund and World Bank buildings in Washington, D.C., the New York Stock Exchange and other financial institutions

- The 2004 Columbus Shopping Mall Bombing Plot

- The 2006 Sears Tower plot

- The 2007 Fort Dix attack plot

- The 2007 John F. Kennedy International Airport attack plot

- The New York Subway Bombing Plot and 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt

The Obama administration has promised the closing of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, increased the number of troops in Afghanistan, and promised the withdrawal of its forces from Iraq.

Casualties[edit source]

According to Joshua Goldstein, an international relations professor at the American University, The Global War on Terror has seen fewer war deaths than any other decade in the past century.[224]

There is no widely agreed on figure for the number of people that have been killed so far in the War on Terror as it has been defined by the Bush Administration to include the war in Afghanistan, the war in Iraq, and operations elsewhere. The International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War and the Physicians for Social Responsibility and Physicians for Global Survival give total estimates ranging from 1.3 million to 2 million casualties.[225] Some estimates for regional conflicts include the following:

Child killed by a car bomb in Kirkuk, July 2011

Footage of leaked Apache gunship strike in Baghdad, July 2007

- Iraq: 62,570 to 1,124,000

-

- Iraq Body Count project documented 110,937–121,227 civilian deaths from violence from March 2003 to December 2012.[226][227][228]

- 110,600 deaths in total according to the Associated Press from March 2003 to April 2009.[229]

- 151,000 deaths in total according to the Iraq Family Health Survey.[230]

- Opinion Research Business (ORB) poll conducted 12–19 August 2007 estimated 1,033,000 violent deaths due to the Iraq War. The range given was 946,000 to 1,120,000 deaths. A nationally representative sample of approximately 2,000 Iraqi adults answered whether any members of their household (living under their roof) were killed due to the Iraq War. 22% of the respondents had lost one or more household members. ORB reported that “48% died from a gunshot wound, 20% from the impact of a car bomb, 9% from aerial bombardment, 6% as a result of an accident and 6% from another blast/ordnance.”[231][232][233]

- Between 392,979 and 942,636 estimated Iraqi (655,000 with a confidence interval of 95%), civilian and combatant, according to the second Lancet survey of mortality.

- A minimum of 62,570 civilian deaths reported in the mass media up to 28 April 2007 according to Iraq Body Count project.[234]

- 4,409 U.S. military dead (929 non-hostile deaths), and 31,926 wounded in action during Operation Iraqi Freedom.[235] 66 U.S. Military Dead (28 non-hostile deaths), and 295 wounded in action during Operation New Dawn.[235]

- Afghanistan: between 10,960 and 249,000[236]

-

- 16,725–19,013 civilians killed according to Cost of War project from 2001 to 2013[237]

-

- According to Marc W. Herold’s extensive database,[238] between 3,100 and 3,600 civilians were directly killed by U.S. Operation Enduring Freedom bombing and Special Forces attacks between 7 October 2001 and 3 June 2003. This estimate counts only “impact deaths”—deaths that occurred in the immediate aftermath of an explosion or shooting—and does not count deaths that occurred later as a result of injuries sustained, or deaths that occurred as an indirect consequence of the U.S. airstrikes and invasion.

-

- In an opinion article published in August 2002 in the magazine The Weekly Standard, Joshua Muravchik of the American Enterprise Institute,[239] questioned Professor Herold’s study entirely by one single incident that involved 25–93 deaths. He did not provide any estimate his own.[240]

-

- In a pair of January 2002 studies, Carl Conetta of the Project on Defense Alternatives estimates that “at least” 4,200–4,500 civilians were killed by mid-January 2002 as a result of the war and Coalition airstrikes, both directly as casualties of the aerial bombing campaign, and indirectly in the resulting humanitarian crisis.

-

- His first study, “Operation Enduring Freedom: Why a Higher Rate of Civilian Bombing Casualties?”,[241] released 18 January 2002, estimates that, at the low end, “at least” 1,000–1,300 civilians were directly killed in the aerial bombing campaign in just the three months between 7 October 2001 to 1 January 2002. The author found it impossible to provide an upper-end estimate to direct civilian casualties from the Operation Enduring Freedom bombing campaign that he noted as having an increased use of cluster bombs.[242] In this lower-end estimate, only Western press sources were used for hard numbers, while heavy “reduction factors” were applied to Afghan government reports so that their estimates were reduced by as much as 75%.[243]

-

- In his companion study, “Strange Victory: A critical appraisal of Operation Enduring Freedom and the Afghanistan war”,[244] released 30 January 2002, Conetta estimates that “at least” 3,200 more Afghans died by mid-January 2002, of “starvation, exposure, associated illnesses, or injury sustained while in flight from war zones”, as a result of the war and Coalition airstrikes.

-

- In similar numbers, a Los Angeles Times review of U.S., British, and Pakistani newspapers and international wire services found that between 1,067 and 1,201 direct civilian deaths were reported by those news organizations during the five months from 7 October 2001 to 28 February 2002. This review excluded all civilian deaths in Afghanistan that did not get reported by U.S., British, or Pakistani news, excluded 497 deaths that did get reported in U.S., British, and Pakistani news but that were not specifically identified as civilian or military, and excluded 754 civilian deaths that were reported by the Taliban but not independently confirmed.[245]

-

- According to Jonathan Steele of The Guardian between 20,000 and 49,600 people may have died of the consequences of the invasion by the spring of 2002.[246]

-

- 2,046 U.S. military dead (339 non-hostile deaths), and 18,201 wounded in action.[235]

-

- A report titled Body Count put together by Physicians for Social Responsibility, Physicians for Global Survival, and International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) concluded that between 185,000–249,000 people had been killed as a result of the fighting in Afghanistan.[236]

- Pakistan: Between 1467 and 2334 people were killed in U.S. drone attacks as of 6 May 2011. Tens of thousands have been killed by terrorist attacks, millions displaced.

- Somalia: 7,000+

-

- In December 2007, The Elman Peace and Human Rights Organization said it had verified 6,500 civilian deaths, 8,516 people wounded, and 1.5 million displaced from homes in Mogadishu alone during the year 2007.[247]

- USA

-

- 1 June 2009, Pvt. William Andrew Long was shot and killed by Abdulhakim Muhammad, while outside a recruiting facility in Little Rock AR.[248][249]

- On 5 November 2009, Nidal Malik Hasan shot and killed 13 people and wounded more than 30 others at Fort Hood, Texas.[250]

Total American casualties from the War on Terror

(this includes fighting throughout the world):

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| U.S. Military killed | 7,008[235] |

| U.S. Military wounded | 50,422[235] |

| U.S. DoD Civilians killed | 16[235] |

| U.S. Civilians killed (includes 9/11 and after) | 3,000 + |

| U.S. Civilians wounded/injured | 6,000 + |

| Total Americans killed (military and civilian) | 10,008 + |

| Total Americans wounded/injured | 56,422 + |

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs has diagnosed more than 200,000 American veterans with PTSD since 2001.[256]

- Yemen

Total terrorist casualties[edit source]

On December 7, 2015, the Washington post reported that since 2001, in five theaters of the war (Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Syria and Somalia) that the total number of terrorists killed ranges from 65,800 to 88,600, with Obama administration being responsible for between 30,000 and 33,000.[257]

Costs[edit source]

A March 2011 Congressional report[258] estimated spending related to the war through the fiscal year 2011 at $1.2 trillion, and that spending through 2021 assuming a reduction to 45,000 troops would be $1.8 trillion. A June 2011 academic report[258] covering additional areas of spending related to the war estimated it through 2011 at $2.7 trillion, and long-term spending at $5.4 trillion including interest.[note 4]

According to the Soufan Group in July 2015, the United States government spends $9.4 million per day in operations against ISIS in Syria and Iraq.[259]

| Expense | CRS/CBO (Billions US$):[260][261][262] | Watson (Billions constant US$):[263] |

| FY2001-FY2011 | ||

| War appropriations to DoD | 1208.1 | 1311.5 |

| War appropriations to DoS/USAID | 66.7 | 74.2 |

| VA Medical | 8.4 | 13.7 |

| VA disability | 18.9 | |

| Interest paid on DoD war appropriations | 185.4 | |

| Additions to DoD base spending | 362.2–652.4 | |

| Additions to Homeland Security base spending | 401.2 | |

| Social costs to veterans and military families to date | 295-400 | |

| Subtotal: | 1283.2 | 2662.1–3057.3 |

| FY2012-future | ||

| FY2012 DoD request | 118.4 | |

| FY2012 DoS/USAID request | 12.1 | |

| Projected 2013–2015 war spending | 168.6 | |

| Projected 2016–2020 war spending | 155 | |

| Projected obligations for veterans’ care to 2051 | 589–934 | |

| Additional interest payments to 2020 | 1000 | |

| Subtotal: | 454.1 | 2043.1–2388.1 |

| Total: | 1737.3 | 4705.2–5445.4 |

Criticism[edit source]

Criticism of the War on Terror addressed the issues, morality, efficiency, economics, and other questions surrounding the War on Terror and made against the phrase itself, calling it a misnomer. The notion of a “war” against “terrorism” has proven highly contentious, with critics charging that it has been exploited by participating governments to pursue long-standing policy/military objectives,[264] reduce civil liberties,[265] and infringe upon human rights. It is argued that the term war is not appropriate in this context (as in War on Drugs) since there is no identifiable enemy and that it is unlikely international terrorism can be brought to an end by military means.[266]

Other critics, such as Francis Fukuyama, note that “terrorism” is not an enemy, but a tactic; calling it a “war on terror”, obscures differences between conflicts such as anti-occupation insurgents and international mujahideen. With a military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan and its associated collateral damage, Shirley Williams maintains this increases resentment and terrorist threats against the West.[267] There is also perceived U.S. hypocrisy,[268][269] media-induced hysteria,[270] and that differences in foreign and security policy have damaged America’s reputation internationally.[271]

Other Wars on Terror[edit source]

In the 2010s, China has also been engaged in its War on Terror, predominantly a domestic campaign in response to violent actions by Uighur separatist movements in the Xinjiang conflict.[272] This campaign was widely criticized in international media due to the perception that it unfairly targets and persecutes Chinese Muslims,[273] potentially resulting in a negative backlash from China‘s predominantly Muslim Uighur population.

Russia has also been engaged on its own, also largely internally focused, counter-terrorism campaign often termed a war on terror, during the Second Chechen War, the Insurgency in the North Caucasus, and the Russian military intervention in the Syrian Civil War.[274] Like China‘s war on terror, Russia‘s has also been focused on separatist and Islamist movements that use political violence to achieve their ends.[275]