California, the most populous state in the United States and third largest in area after Alaska and Texas, has been the subject of more than 220 proposals to divide it into multiple states since its admission to the United States in 1850,[1] including at least 27 significant proposals in the first 150 years of statehood.[2] In addition, there have been some calls for the secession of multiple states or large regions in the American West (such as the proposal of Cascadia) which often include parts of Northern California.

One-third of California residents in a 2016–2017 poll supported peacefully seceding from the United States, up from 20% in 2014.[3]A new poll taken in 2018 found that only 14% of voters supported peacefully seceding from the United States, down from 33% in 2017.

Prior California partitions

California was partitioned in its past. What under Spanish rule was called the Province of the Californias (1768–1804) was divided into Alta California (Upper California) and Baja California (Lower California) in 1804 at the line separating the Franciscan missions in the north from the Dominican missions in the south.

After the Mexican–American War, Alta California was admitted to the United States as the present-day State of California. Baja California remained under Mexican rule.

In 1888, under the government of President Porfirio Díaz, Baja California became a federally administered territory called the North Territory of Baja California (“north territory” because it was the northernmost territory in the Republic of Mexico). In 1952, the northern portion of this territory (above 28°N) became the 29th state of Mexico, called Baja California; the sparsely populated southern portion remained a federally administered territory. In 1974, it became the 31st state of Mexico, admitted as Baja California Sur.

History of partition movements

Pre-statehood

The territory that became the present state of California was acquired by the U.S. as a result of the Mexican–American Warand subsequent 1848 Mexican Cession. After the war, a confrontation erupted between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North regarding the status of these acquired territories. Among the disputes, the South wanted to extend the Missouri Compromise line (36°30′ parallel north), and thus slave territory, west to Southern California and to the Pacific coast, while the North did not.[5]

Starting in late 1848, Americans and foreigners of many different countries rushed into California for the California Gold Rush, exponentially increasing the population. In response to growing demand for a better more representative government, a Constitutional Convention was held in 1849. The delegates there unanimously outlawed slavery, and had no interest in extending the Missouri Compromise Line through California; the lightly populated southern half never had slavery and was heavily Hispanic.[6] They thus applied for statehood in the current boundaries. As part of the Compromise of 1850, the South reluctantly acceded to having California be a free state, and it officially became the 31st state in the union on September 9, 1850.

Post-statehood[edit source]

Southern California attempted three times in the 1850s to achieve a separate statehood or territorial status from Northern California.

- In 1855, the California State Assembly passed a plan to trisect the state.[7] All of the southern counties as far north as Monterey, Merced, and part of Mariposa, then sparsely populated but today containing about two-thirds of California’s total population, would become the State of Colorado (the name Colorado was later adopted for another territory established in 1861), and the northern counties of Del Norte, Siskiyou, Modoc, Humboldt, Trinity, Shasta, Lassen, Tehama, Plumas, and portions of Butte, Colusa (which included what is now Glenn County), and Mendocino, a region which today has a population of little more than half a million, would become the State of Shasta. The primary reason was the size of the state’s territory. At the time, the representation in Congress was too small for such a large territory, it seemed too extensive for one government, and the state capital was too inaccessible because of the distances to Southern California and various other areas. The bill eventually died in the Senate as it became very low priority compared to other pressing political matters.[7]

- In 1859, the legislature and governor approved the Pico Act (named after the bill’s sponsor Andrés Pico, state senator from Southern California) splitting off the region south of the 36th parallel north as the Territory of Colorado.[8][9][10] The primary reason cited was the difference in both culture and geography between Northern and Southern California. It was signed by the State governor John B. Weller, approved overwhelmingly by voters in the proposed Territory of Colorado, and sent to Washington, D.C. with a strong advocate in Senator Milton Latham. However the secession crisis and American Civil War following the election of Lincoln in 1860 prevented the proposal from ever coming to a vote.

- In the late 19th century, there was serious talk in Sacramento of splitting the state in two at the Tehachapi Mountainsbecause of the difficulty of transportation across the rugged range. The discussion ended when it was determined that building a highway over the mountains was feasible; this road later became the Ridge Route, which today is Interstate 5over Tejon Pass.

20th century[edit source]

- Since the mid-19th century, the mountainous region of northern California and parts of southwestern Oregon have been proposed as a separate state. In 1941, some counties in the area ceremonially seceded, one day a week, from their respective states as the State of Jefferson. This movement disappeared after America’s entry into World War II, but the notion has been rekindled in recent years.[14]

- The California State Senate voted on June 4, 1965, to divide California into two states, with the Tehachapi Mountains as the boundary. Sponsored by State Senator Richard J. Dolwig (R-San Mateo), the resolution proposed to separate the 7 southern counties, with a majority of the state’s population, from the 51 other counties, and passed 27-12. To be effective, the amendment would have needed approval by the State Assembly, by California voters, and by the United States Congress. As expected by Dolwig, the proposal did not get out of committee in the Assembly.[15]

- In 1992, State Assemblyman Stan Statham sponsored a bill to allow a referendum in each county on a partition into three new states: North, Central, and South California. The proposal passed in the State Assembly but died in the State Senate.[16]

21st century[edit source]

-

2009: Martin Hutchinson’s proposal

San Diego/ Orange County/ Inland EmpireGreater Los AngelesSan Francisco/ Sacramento/ Santa Cruz/ Silicon ValleyNorthern/Central Valley

- In the wake of the 2003 gubernatorial recall, Tim Holt and Martin Hutchinson proposed in separate newspaper op-eds that the state should split into as many as four new states, dividing distinct geographically and politically defined regions as the Bay Area, North Coast, and Central Valley, as well as the historic Shasta/Jefferson region, into their own states.

-

2009: Bill Maze‘s proposal

- In early 2009, former State Assemblyman Bill Maze began lobbying to split thirteen coastal counties, which usually vote Democratic, into a separate state to be known as either “Coastal California” or “Western California.” Maze’s primary reason for wanting to split the state was because of how “conservatives don’t have a voice” and how Los Angeles and San Francisco “control the state.” The counties that would make up the new state would be Marin, Contra Costa, Alameda, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, San Benito, Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura, and Los Angeles Counties. It has also been proposed that the state be split in two simply at the straight divide of the 120th meridian west, much like its border with the state of Nevada.

-

2011: Jeff Stone’s proposal

South California

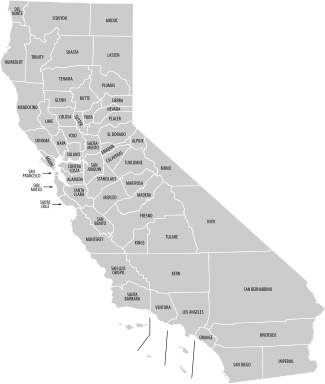

- In June 2011, Republican Riverside County Supervisor Jeff Stone called for Riverside, Imperial, San Diego, Orange, San Bernardino, Kings, Kern, Fresno, Tulare, Inyo, Madera, Mariposa and Mono counties (see map, highlighted in red) to separate from California to form the new state of South California. Officials in Sacramento responded derisively, with governor Jerry Brown‘s spokesperson saying “A secessionist movement? What is this, 1860? It’s a supremely ridiculous waste of everybody’s time.”[20] and fellow supervisor Bob Buster calling Stone “crazy,” suggesting “Stone has gotten too much sun recently.”[21]

- In September 2013, county supervisors in both Siskiyou County and Modoc County voted to join a bid to separate and create a new “State of Jefferson“.[14] Mark Baird, spokesperson for the Jefferson Declaration Committee, is reported to have said the group hopes to obtain commitments from as many as a dozen counties, after which they will ask the state legislature to permit formation of the new state based on Article 4, Section 3 of the US Constitution. In January 2014, supervisors in Glenn County voted in favor of separation,[22] and in April 2014, Yuba County supervisors voted to become the fourth California county to join the movement.[23] On June 3, 2014, residents in Del Norte County voted against separation by 58 percent to 42 percent,[24] however, voters in Tehama County supported a separation initiative by 57 percent to 43 percent.[25] On July 22, 2014, Sutter County voted 5-0 to join the State of Jefferson.

Six Californias

Six Californias was a proposed initiative to split the U.S. state of California into six states. It failed to qualify as a California ballot measure for the 2016 state elections due to receiving insufficient signatures.

Venture capitalist Tim Draper launched the measure in December 2013. He spent in excess of $5 million to try to qualify the proposition for the ballot, with nearly $450,000 for political consultants.[1] Had the measure passed, it would not have legally split California immediately; consent would eventually need to be given by both the California State Legislature and the U.S. Congress to admit the new states to the union per Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution. Rather, the measure would have established several procedures within the state government and its 58 counties to prepare California for the proposed split, and instructed the Governor of Californiato submit the state-splitting proposal to Congress.[2]

The proposed states would have been named Jefferson, North California, Silicon Valley, Central California, West California, and South California. Draper’s stated reasoning for the proposal was that the state is too large and ungovernable, and he therefore wanted to split California to produce six smaller and more efficient state governments.

Opponents argued that it would have been a waste of money and resources to split California and create these new governments. Critics also charged that this was a money and political power grab designed to separate California’s wealthy areas from the poor, and to diminish the state’s reliability as a predominantly Democratic Party-supporting “blue state“.

Background[edit source]

Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution outlines the procedure for the admission of new U.S. states. It reads:

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

There are several precedents for the partition of states:

- Vermont, admitted in 1791, was created from territory to which a disputed claim was asserted by New York. (It had formerly also been claimed by New Hampshire, but that claim had been given up in 1782. Vermont had already been under a de facto separate government for over a decade.) New York’s legislature consented in 1790.

- Kentucky split from Virginia in 1792. Virginia’s legislature consented to the partition when the Articles of Confederationwere still in effect, but then the new Constitution of the United States superseded the Articles and the legislature’s consent was passed again.[3]

- North Carolina ceded territory to the federal government which became the Southwest Territory and five years later in 1796 became the state of Tennessee;

- Georgia ceded land that later became part of Alabama.

Two instances were a result of slavery:

- The 1820 Missouri Compromise balanced the number of free and slave states by splitting Maine from Massachusetts in 1820 and admitting Missouri in 1821. However, the partition of Maine from Massachusetts had been proposed well over three decades earlier for reasons other than slavery.

- West Virginia was admitted to the U.S. as a separate state in 1863 when the Union-loyal Restored Government of Virginiabroke from Virginia after Virginia joined the Confederate States of America in 1861, though most of the new state’s counties had in fact supported secession.

California has been the subject of more than 220 proposals to divide it into multiple states,[4] including at least 27 serious proposals.[5] Several of these attempts proposed the creation of a State of Jefferson that would span the contiguous, mostly rural area of southern Oregon and northern California.

Ballot qualification process

Six Californias was introduced in December 2013 by Silicon Valley venture capitalist Tim Draper.[6][7] California Secretary of State Debra Bowen approved Draper to begin collecting petition signatures in February 2014.[8] The petition needed to submit sufficient valid signatures of registered California voters by July 18, 2014, to qualify as a November election ballot proposition.[9] As the petition deadline drew closer, Draper suggested that the initiative would be postponed to 2016, since that would allow more time to educate the public on the initiative.[10][11]

On July 14, Draper announced that the proposal received 1.3 million signatures, enough to qualify for the ballot, and began submitting them to elections officials.[12][13] If sufficient signatures are verified, per California law, it would qualify for the November 2016 state ballot. On September 12, 2014, California state election officials announced that based on random sampling of the submitted signatures, only an estimated 752,685 signatures were valid, which was insufficient not only to qualify the initiative for the ballot, but also to trigger a complete verification of all submitted signatures.[14]

These estimated valid signatures were 66.15% of the 1,137,844 submitted signatures.[15] At least 807,615 signatures, 70.98% of the submitted signatures, had to be valid for the measure to qualify for the ballot. At least 767,235 signatures, 67.43% of the submitted signatures, had to be estimated to be valid in order for the petition to qualify for a second mandatory phase to review all of the submitted signatures, not just random samples.[16]

Also on September 12, 2014, the campaign announced its intent to “… conduct a review of the signatures determined to be invalid by the registrars in several counties to determine if they were in fact valid signatures.” [17] To qualify for a full check of all signatures in all fifty-eight counties, the review must find about 450 wrongly invalidated signatures among those submitted in the fifteen counties that sampled 3% of the total signatures submitted in each of those fifteen counties. As of November 17, 2014, the campaign has not updated its web site with information about the results of their review of the supposedly invalid signatures.

Opponents of the initiative filed a complaint with Secretary of State Debra Bowen on July 17, 2014, asking her office to investigate allegations of voter fraud. The complaint, filed on behalf of the OneCalifornia committee formally opposing the Six Californias initiative, follows reports that signature gatherers for Six Californias claimed that those who signed “would be opposing the Attorney General of California’s intention to split the state into six states” – the exact opposite of the petitions intentions.[18] Signature gathering for Six Californias was carried out by Arno Political Consultants.[19] The campaign for Six Californias also paid $51,000 to Crowds on Demand, a service that sends paid actors to form crowds at gatherings such as political rallies.[20][21] Organizers for Six Californias stated Crowds on Demand provided personnel for signature gathering.[22]

Measure details[edit source]

The measure outlined the proposed new states, then established several procedures within the state government and all the counties to prepare California for the proposed split. The proposal would then have needed the approval of voters in California, the Congress of the United States (per Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution), and the California State Legislature.[9]

Proposed states[edit source]

Six Californias would have divided the state’s 58 counties among six new states: Jefferson (based on the historic State of Jefferson proposal), North California, Silicon Valley, Central California, West California, and South California.[9]

| Proposed state | Estimated Population[2] |

|---|---|

| Jefferson | 949,409 |

| North California | 3,820,438 |

| Silicon Valley | 6,828,617 |

| Central California | 4,232,419 |

| West California | 11,563,717 |

| South California | 10,809,997 |

Jefferson[edit source]

The state of Jefferson would have been created from the far north part of California, bordering Oregon, consisting of fourteen counties: Butte, Colusa, Del Norte, Glenn, Humboldt, Lake, Lassen, Mendocino, Modoc, Plumas, Siskiyou, Shasta, Tehama, and Trinity.[23] Unlike the historic State of Jefferson proposal, this new state would not include any territory from Oregon.

North California[edit source]

The state of North California would have been south of Jefferson spanning from the Pacific Ocean to Nevada. North California would have consisted of thirteen counties: Amador, El Dorado, Marin, Napa, Nevada, Placer, Sacramento, Sierra, Solano, Sonoma, Sutter, Yolo and Yuba.[23]

Silicon Valley[edit source]

The state of Silicon Valley would have spanned the coastline from San Francisco to Monterey. It would have consisted of eight counties: Alameda, Contra Costa, San Benito, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz and Monterey.[23]

Central California[edit source]

The state of Central California would have been between Silicon Valley and Nevada. It would have consisted of the fourteen counties north of Los Angeles and south of Sacramento: Alpine, Calaveras, Fresno, Inyo, Kern, Kings, Madera, Mariposa, Merced, Mono, San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Tulare and Tuolumne.[23]

West California[edit source]

The state of West California would have been south of Silicon Valley and Central California, and west of the current San Bernardino County. It would have consisted of four counties: Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, Los Angeles and Ventura.[23]

South California[edit source]

The state of South California would have been made up of the southernmost part of the state. It would have consisted of five counties: Imperial, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and San Diego.[23]

State-splitting process and other procedures[edit source]

The above division was not set in stone. The proposal allowed a county along one of the proposed new state borders to join an adjacent state instead, subject to the approval of both that county’s voters (via a county ballot measure) and its Boards of Supervisors by November 15, 2017.[2]

A board of 24 commissioners would also have been appointed to negotiate how to divide California’s existing assets and liabilities among the new states. The initiative also explicitly stated that the Governor of California will be required to submit the state-splitting proposal to Congress by January 1, 2018.[2]

In addition, California’s charter counties would have been allowed more power over municipal affairs that currently may be controlled by city governments. This change was meant for the interim period between the passing of the initiative and congressional approval of the new states, but would have remained in place even if Congress did not pass the state-splitting proposal.[2]

In final section of the initiative, “the official proponent of the initiative” (Draper) was to be appointed as an “Agent of the State of California” for the purpose of defending the proposal against legal challenges.[24]

Analysis[edit source]

The California Legislative Analyst’s Office, in a report that covered a wide variety of impacts, noted a wide disparity of incomes and tax bases in the proposed states. The report estimated that the state of Silicon Valley would have the nation’s highest per capita personal income (PCPI) whereas the state of Central California would have the nation’s lowest PCPI. During the two-year period between passage of the measure, the 24-member Commission would have had to decide how the California state resources would be divided and how the present debt would be distributed between the six states. The areas most affected would have been required to make decisions including school funding, health and social services, water management, and the handling of prisons. Each new state would have also been faced with new budgets, establishing methods of revenue, funding infrastructure, public employee compensation, and new, revised or discarded laws. Most likely, many issues would have had to be resolved by the courts.[2] The Huffington Post further published a map detailing how splitting California would result in these separate rich states and poor states.[25]

Vikram Amar wrote a preliminary analysis of the difficulties that the Six Californias measure would face. His piece, published by the law group Justia, raised several constitutional questions on the proposal, including whether the people of a U.S. state can authorize such a split by popular initiative, and whether several new states can be validly created under Article IV by splitting the territory of a single existing state. Furthermore, Draper, as the appointed “Agent of the State of California” for the purpose of defending the proposal in court, may not actually be able to do so because of both the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Hollingsworth v. Perry; and Article II, Section 12, of the California Constitution that prohibits any constitutional amendment that names a specific individual to hold a particular office.[24] Amar also wrote that the measure might be blocked by the California courts on grounds that it is a revision to the California constitution instead of an amendment. A proposed revision to the California constitution, a change that substantially alters the state’s basic governmental framework, must originate from either the Legislature or a constitutional convention, not from a ballot initiative.[26]

A prior study by the state assembly report would allow for multistate reorganization of the university system, and any other present state function. It would be the job of the 24 member commission to decide.[2] If the university system were to split, a report identified a potential increase in tuition for current Californians who attend a University of California campus, particularly residents in California’s most northern state of Jefferson who would not have a single UC campus in the state. Based on the report’s findings, Six Californias could result in over 60% of California students being classified as out-of-state, costing Californian families $2.5 billion more per year.[27] California’s prison system is also unequally spread out. If the prison system were to split, the new urban states of Silicon Valley and West California would each have to construct several new prisons since most of the current ones in California are located in the rural areas. California’s current water and water rights issueswould also have to have been resolved among the new states. The California, Hetch Hetchy, Los Angeles, Mokelumne, and other major aqueducts will cross the new state lines. If not reorganized into a multistate function, this will result in the new states of Silicon Valley and West California having to heavily rely on importing water from the other states.[2]

The report by the California Legislative Analyst’s Office specifically named several other major issues that could have been affected by the decisions made by the leaders of each new state: crime, public safety and gun control/ownership; economic development; the environment; public employee pensions; laws related to marriage and family; taxes; and transportation and other infrastructure.[2] Each new state could adopt different laws, either stricter or more lenient, on those issues than what California currently has on the books. These differing policies would have in turn eventually result in long-term demographic and economic changes, as various groups of people will want to migrate to those new states with laws more favorable to them.[2]

Vikram Amar agrees there are governance problems in California. The demographic, cultural, political and economic differences between the urban and rural areas of California are obvious, as are the tensions between the major urban areas of San Francisco and Los Angeles. However splitting California is a radical change, and a major question is whether the newly formed poorer states can make it without the tax revenues from the major metropolitan areas. The political makeup in Washington D.C. at the time of approval, may determine the success or failure of six Californias. Twelve Senators would result from six Californias, as well as a probable change in total house House seats and their electoral votes. According to Amar, “we could expect four [Senators] (from Silicon Valley and West California) to consistently be Democrats, and four (from Jefferson and Central California) to lean Republican, with the other four (from Northern California and South California) harder to predict”.[24]

Stances on the proposal[edit source]

Support[edit source]

Tim Draper indicated that the initiative was motivated by the belief that California is ungovernable as is with legislature unable to keep up on issues in all the state’s regions, especially in areas such as job creation, education, affordable housing, and water and transportation infrastructure.[9][28] Furthermore, he believed that the current state government is getting out of touch with the people of California.[29] According to Draper, splitting up the state would allow the resulting new state governments to be closer to their people than the current California state government.[9]

Opposition[edit source]

OneCalifornia, a bi-partisan committee to oppose the Six Californias ballot proposal, was formed in April 2014.[30] It is co-chaired by Joe Rodota, former Cabinet Secretary for Governor Pete Wilson; and Steven Maviglio, former Press Secretary to Governor Gray Davis.[31] The committee suggested that the initiative was damaging the state’s image in the world economy. Rodota stated: “Every day this measure marches its way toward the ballot it damages the California brand as the nation’s economic powerhouse. It has negative implications that could cost California’s businesses and taxpayers tens of billions of dollars.”[32] In an opinion piece in the U-T San Diego, Maviglio and Rodota wrote that if the measure passes, it “will set in motion the most bureaucratic, costly, paper-pushing process in our history … we’d spend years doing nothing more than rewriting laws, duplicating government offices, and spending billions of dollars unnecessarily.”[33] Furthermore, that it could increase the lobbying industry sixfold in California “to deal with the flood of open questions”, and would be a burden on California businesses due to the increase of federal regulations regarding interstate commerce.[33]

The segregation of the incomes and tax bases led to criticism that the proposal is merely a money and political power grab for Silicon Valley and California’s other wealthy areas.[34] Phillip Bump of the Washington Post wrote that “this entire plan is really about creating Silicon Valley as its own state. Therefore Silicon Valley gets to be a state called ‘Silicon Valley,’ and it gets to make its politics and its money more dense, and everyone in the idyllic dream of Silicon Valley gets to be happy.”[35]

Brendan Nyhan said that the idea would be unlikely to pass Congress due to disruption it would cause in the political balance of the U.S. Senate, as well as other sticking points.[8] Opponents said that the initiative was a thinly disguised Republican power play aimed at diminishing the electoral votes that have historically gone to Democrats in California.[36] In a survey of the California congressional delegation, The Hill found that the Democrats opposed the proposition, while the Republicans were generally divided.[37]

Thus, a couple of political experts countered that the measure would not get the approval of all the parties needed; the voters would not necessarily wish to break up the state with the cost of setting up six new state governments and five new capitals, and Congress may not want five more states in the mix.[9]

-

2018: Paul Preston’s proposal

New California

- New California: On January 16th, 2018, the 501(c)(4) organization New California, organized by conservative radio talk show host Paul Preston, published its proposed state’s Declaration of Independence. They cited the split for being the 48th out of 50 for business climate and also cited high taxes and supposed failure to follow the state and federal constitutions. New California would include the rural counties that make up most of the state’s area north, south and east of the more heavily populated coastal areas between counties around San Francisco and Los Angeles.[33] New California would also include the urban areas of Contra Costa County, Orange County, and San Diego County, bringing the population to around 20 million

Cal 3

Cal3 is a proposal to split the US state of California into three new states, California, Northern California, and Southern California. It was proposed by Tim Draper, a Menlo Parkbillionare who previously proposed the Six Californias plan, which failed to get enough signatures to get onto the ballot. Proponents of the plan say that the California state government is controlling too large of a population and would be more effective if it were split into three. Opponents say that it is a waste of money and energy.

If successful, Article IV, Section 3 of the US Constitution requires both the US Congress and California State Legislature to approve any partition of an existing state.

Proposed divisions by county

Under this plan, the existing state of California would be split into three new states, tentatively named California, Northern California, and Southern California.[1][2] The plan has received more than enough signatures than are needed to appear on the ballot in November 2018, and it will become an official proposition if the signatures are found to be valid.

Proposed state of California[edit source]

Proposed state of Northern California[edit source]

- Alameda

- Alpine

- Amador

- Butte

- Calaveras

- Colusa

- Contra Costa

- Del Norte

- El Dorado

- Glenn

- Humboldt

- Lake

- Lassen

- Marin

- Mariposa

- Mendocino

- Merced

- Modoc

- Napa

- Nevada

- Placer

- Plumas

- Sacramento

- San Francisco

- San Joaquin

- San Mateo

- Santa Clara

- Santa Cruz

- Shasta

- Sierra

- Siskiyou

- Solano

- Sonoma

- Stanislaus

- Sutter

- Tehama

- Trinity

- Tuolumne

- Yolo

- Yuba

Proposed state of Southern California[edit source]

Secession

Ecotopia[edit source]

Writer Ernest Callenbach wrote a 1975 novel, entitled Ecotopia, in which he proposed a full-blown secession of Northern California, Oregon, and Washington from the United States in order to focus upon environmentally friendly living and culture. He later abandoned the idea stating: “We are now fatally interconnected, in climate change, ocean impoverishment, agricultural soil loss, etc. etc. etc.”[37]

Cascadia

While mostly consisting of Washington, Oregon, Idaho and British Columbia in Canada, proposals for an independent Cascadia often include portions of northern California.

California National Party[edit source]

Founded in 2014, California National Party (CNP) is a political party advocating a progressive platform. The CNP is running candidates throughout California at the state and local level, beginning with the 2018 election cycle. The CNP also seeks, as a long-term goal, the secession of California from the United States by legal and peaceful means.

Calexit[edit source]

In the wake of Republican nominee Donald Trump winning the 2016 presidential election, a fringe movement organized by Yes California, referred to as “Calexit” – a term inspired by the successful 2016 Brexit referendum, arose in a bid to gather the 585,407 signatures necessary to place a secessionist question on the 2018 ballot.[38]