Category Archives: Labour

UK Labour Leader Jeremy Corbyn Accused Of Anti-Semitism

Ed Miliband

| The Right Honourable Ed Miliband MP |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Leader of the Opposition | |||

| In office 25 September 2010 – 8 May 2015 |

|||

| Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||

| Prime Minister | David Cameron | ||

| Preceded by | Harriet Harman (Acting) | ||

| Succeeded by | Harriet Harman (Acting) | ||

| Leader of the Labour Party | |||

| In office 25 September 2010 – 8 May 2015 |

|||

| Deputy | Harriet Harman | ||

| Preceded by | Harriet Harman (Acting) | ||

| Succeeded by | Harriet Harman (Acting) | ||

| Shadow Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change | |||

| In office 11 May 2010 – 8 October 2010 |

|||

| Leader | Harriet Harman (Acting) | ||

| Preceded by | Greg Clark | ||

| Succeeded by | Meg Hillier | ||

| Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change | |||

| In office 3 October 2008 – 11 May 2010 |

|||

| Prime Minister | Gordon Brown | ||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||

| Succeeded by | Chris Huhne | ||

| Minister for the Cabinet Office Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster |

|||

| In office 28 June 2007 – 3 October 2008 |

|||

| Prime Minister | Gordon Brown | ||

| Preceded by | Hilary Armstrong | ||

| Succeeded by | Liam Byrne | ||

| Minister for the Third Sector | |||

| In office 6 May 2006 – 28 June 2007 |

|||

| Prime Minister | Tony Blair Gordon Brown |

||

| Preceded by | Phil Woolas | ||

| Succeeded by | Phil Hope | ||

| Member of Parliament for Doncaster North |

|||

| Assumed office 5 May 2005 |

|||

| Preceded by | Kevin Hughes | ||

| Majority | 11,780 (29.8%) | ||

| Personal details | |||

| Born | Edward Samuel Miliband 24 December 1969 London, England |

||

| Political party | Labour | ||

| Spouse(s) | Justine Thornton (m. 2011) | ||

| Children | 2 | ||

| Alma mater | Corpus Christi College, Oxford London School of Economics |

||

|

|||

Edward Samuel “Ed” Miliband (born 24 December 1969) is a British politician who was Leader of the Labour Party as well as Leader of the Opposition between 2010 and 2015. He has been the Member of Parliament(MP) for Doncaster North since 2005 and served in the Cabinet from 2007 to 2010 under Prime Minister Gordon Brown. He and his brother, David Miliband, were the first siblings to sit in the Cabinet simultaneously since Edward andOliver Stanley in 1938.

Born in London, Miliband graduated from Corpus Christi College at theUniversity of Oxford, and the London School of Economics, becoming first a television journalist, a Labour Party researcher and a visiting scholar atHarvard University before rising to become one of Chancellor Gordon Brown’s confidants and Chairman of HM Treasury‘s Council of Economic Advisers.

Miliband was elected to Parliament in 2005, succeeding the retiring Labour MPKevin Hughes in Doncaster North. Prime Minister Tony Blair made MilibandParliamentary Secretary to the Cabinet Office in May 2006 and when Gordon Brown became Prime Minister in 2007, he appointed Miliband Minister for the Cabinet Office and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Miliband was subsequently promoted to the new post of Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change, a position he held from 2008 to 2010.

After Labour was defeated in the May 2010 general election, Brown resigned as leader and in September 2010, Miliband was elected Leader of the Labour Party. Miliband’s tenure as Labour leader was characterised by a leftward shift in his party’s policies and opposition to the Conservative–Liberal Democrat Coalition government‘s cuts to the public sector. He led his party into several elections, including the 2014 European Parliament election and the 2015 general election. Following Labour’s loss to the Conservative Party at the general election, Miliband announced his resignation as leader on 8 May 2015 and instructed the party to put into motion the processes to elect a new leader. He was succeeded in the ensuing leadership election by Jeremy Corbyn.

Early life and education[edit]

Born in University College Hospital in Fitzrovia, London, Miliband is the younger son of immigrant parents.[2][3] His mother, Marion Kozak, a human rights campaigner and early CND member, is a Polish Jew who survived the Holocaust thanks to being protected by Catholic Poles.[4] His father, Ralph Miliband, was a Belgian-born Polish Jewish Marxist academic whose father fled with him to England during World War II.[5][6] The family lived on Edis Street in Primrose Hill, London. His elder brother, David Miliband, still owns the house today.[7]

Ralph Miliband left his academic post at the London School of Economics in 1972 to take up a chair at the University of Leeds as a Professor of Politics. His family moved to Leeds with him in 1973 and Miliband attended Featherbank Infant School in Horsforth between 1974 and 1977, during which time he became a fan of Leeds United.[8]

Due to his father’s later employment as a roving teacher, Miliband spent two spells living in Boston, Massachusetts, one year when he was seven and onemiddle school term when he was twelve.[9] Miliband remembered his time in the US as one of his happiest, during which he became a fan of American culture, watching Dallas[2] and following the Boston Red Sox[10] and the New England Patriots.[11]

Between 1978 and 1981, Ed Miliband attended Primrose Hill Primary School, near Primrose Hill, in Camden and then from 1981 to 1989, Haverstock Comprehensive School in Chalk Farm. He learned to play the violin while at school,[12] and as a teenager, he reviewed films and plays on LBC Radio‘s Young London programme as one of its fortnightly “Three O’Clock Reviewers”. After completing his O-levels, he worked as an intern to family friend Tony Benn, theMP for Chesterfield.[13]

In 1989, Miliband gained four A Levels – in Mathematics (A), English (A), Further Mathematics (B) and Physics (B) – and then read Philosophy, Politics and Economics at Corpus Christi College, Oxford. In his first year, he was elected JCR President, leading a student campaign against a rise in rent charges. In his second year he dropped philosophy, and was awarded an upper second class Bachelor of Arts degree. He went on to graduate from the London School of Economics with a Master of Science in Economics.[12]

Early political career[edit]

Special Adviser[edit]

In 1992, after graduating from the University of Oxford, Miliband began his working career in the media as a researcher to co-presenter Andrew Rawnsley in the Channel 4 show A Week in Politics.[14] In 1993, Shadow Chief Secretary to the Treasury Harriet Harman approached Rawnsley to recruit Miliband as her policy researcher and speechwriter.[15] At the time, Yvette Cooper also worked for Harman as part of Labour’s Shadow Treasury team.

In 1994, when Harriet Harman was moved by the newly elected Labour Leader Tony Blair to become Shadow Secretary of State for Employment, Miliband stayed on in the Shadow Treasury team and was promoted to work for Shadow ChancellorGordon Brown.[16] In 1995, with encouragement from Gordon Brown, Miliband took time out from his job to study at the London School of Economics, where he obtained a Masters in Economics.[12] After Labour’s 1997 landslide victory, Miliband was appointed as a special adviser to Chancellor Gordon Brown from 1997 to 2002.[17]

Harvard[edit]

On 25 July 2002, it was announced that Miliband would take a 12-month unpaid sabbatical from HM Treasury to be avisiting scholar at the Center for European Studies of Harvard University for two semesters.[18] He spent his time at Harvard teaching economics,[19] and stayed there after September 2003 for an additional semester teaching a course titled “What’s Left? The Politics of Social Justice”.[20] During this time, he was granted “access” to Senator John Kerry and reported to Brown on the Presidential hopeful’s progress.[21] After Miliband returned to the UK in January 2004 Gordon Brown appointed him Chairman of HM Treasury’s Council of Economic Advisers as a replacement for Ed Balls, with specific responsibility for directing the UK’s long-term economic planning.[22]

Parliament[edit]

In early 2005, Miliband resigned his advisory role to HM Treasury to stand for election.Kevin Hughes, then the Labour MP for Doncaster North, announced in February of that year that he would be standing down at the next election due to being diagnosed withmotor neurone disease. Miliband applied for selection to be the candidate in the safe Labour seat and won, beating off a close challenge from Michael Dugher, then a SPADto Defence Secretary Geoff Hoon.[23] Dugher would later become an MP in 2010.

Gordon Brown visited Doncaster North during the general election campaign to support his former adviser.[24] Miliband was elected to Parliament on 5 May 2005, with over 50% of the vote and a majority of 12,656. He made his maiden speech in the House of Commons on 23 May, responding to comments made by future Speaker John Bercow.[25] In Tony Blair’s cabinet reshuffle in May 2006, he was made theParliamentary Secretary to the Cabinet Office, as Minister for the Third Sector, with responsibility for voluntary and charity organisations.[26][27]

Cabinet[edit]

On 28 June 2007, the day after Gordon Brown had become Prime Minister, Miliband was sworn of the Privy Council and appointed Minister for the Cabinet Office andChancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, being promoted to the Cabinet.[28] This meant that he and his brother, Foreign Secretary David Miliband, became the first brothers to serve in a British Cabinet since Edward and Oliver Stanley in 1938.[29] He was additionally given the task of drafting Labour’s manifesto for the 2010 general election.[30]

On 3 October 2008, Miliband was promoted to become Secretary of State for the newly created Department of Energy and Climate Change in a Cabinet reshuffle.[31] On 16 October, Miliband announced that the British government would legislate to oblige itself to cut greenhouse emissions by 80% by 2050, rather than the 60% cut in carbon dioxide emissions previously announced.[32]

In March 2009, while Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change, Miliband attended the UK premiere of climate-change film The Age of Stupid, where he was ambushed by actor Pete Postlethwaite, who threatened to return his OBE and vote for any party other than Labour if the Kingsnorth coal-fired power station were to be given the go-ahead by the government.[33] A month later, Miliband announced to the House of Commons a change to the government’s policy on coal-fired power stations, saying that any potential new coal-fired power stations would be unable to receive government consent unless they could demonstrate that they would be able to effectively capture and bury 25% of the emissions they produce immediately, with a view to seeing that rise to 100% of emissions by 2025. This, a government source told the Guardian, effectively represented “a complete rewrite of UK energy policy for the future”.[34]

Miliband represented the UK at the 2009 Copenhagen Summit, from which emerged a global commitment to provide an additional US$10 billion a year to fight the effects of climate change, with an additional $100 billion a year provided by 2020.[35] The conference was not able to achieve a legally binding agreement. Miliband accused China of deliberately foiling attempts at a binding agreement; China explicitly denied this, accusing British politicians of engaging in a “political scheme”.[36]

During the 2009 parliamentary expenses scandal, Miliband was named by the Daily Telegraph as one of the “saints” of the scandal, due to his claiming one of the lowest amounts of expenses in the House of Commons and submitting no claims that later had to be paid back.[37]

Leadership of the Labour Party[edit]

Leadership election[edit]

Following the formation of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat Coalition Government on 11 May 2010, Gordon Brown resigned as Prime Minister and Leader of the Labour Party with immediate effect. In accordance with the Labour constitution, Deputy Leader Harriet Harman took over as Acting Leader and became Leader of the Opposition. On 14 May, Miliband announced that he would stand as a candidate in the forthcoming election for the leadership of the Labour Party.[38] He launched his campaign during a speech given at a Fabian Society conference at the School of Oriental and African Studies and was nominated by 62 fellow Labour MPs. The other candidates were left-wing backbencher Diane Abbott, Shadow Education Secretary Ed Balls, Shadow Health Secretary Andy Burnham and Miliband’s elder brother, Shadow Foreign Secretary David Miliband.[39][40]

On 23 May, former Labour Leader Neil Kinnock announced that he would endorse Ed Miliband’s campaign, saying that he had “the capacity to inspire people” and that he had “strong values and the ability to ‘lift’ people”.[41] Other senior Labour figures who backed the younger Miliband included Tony Benn and former Deputy Leaders Roy Hattersley and Margaret Beckett. By 9 June, the deadline for entry into the leadership election, Miliband had been nominated by just over 24% of the Parliamentary Labour Party, double the amount required. By September, Miliband had received the support of six trade unions, including bothUnite and UNISON, 151 of the 650 Constituency Labour Parties, three affiliated socialist societies, and half of LabourMEPs.[42]

Ed Miliband subsequently won the election, the result of which was announced on 25 September 2010, after second, third and fourth preferences votes were counted, achieving the support of 50.654% of the electoral college, defeating his brother by 1.3%.[43] In the fourth and final stage of the redistribution of votes after three candidates had been eliminated, Ed Miliband led in the trade unions and affiliated organisations section of the electoral college (19.93% of the total to David’s 13.40%), but in both the MPs and MEPs section (15.52% to 17.81%), and Constituency Labour Party section (15.20% to 18.14%), came second. In the final round, Ed Miliband won with a total of 175,519 votes to David’s 147,220 votes.[44]

Leader of the Opposition[edit]

On becoming Leader of the Labour Party on 25 September 2010, Miliband also became Leader of the Opposition. At 40, he was the youngest leader of the party ever. At his first Prime Minister’s Questions on 13 October 2010, he raised questions about the government’s announced removal of a non-means tested child benefit.[45] During the 2011 military intervention in Libya, Miliband supported UK military action against Muammar Gaddafi.[46] Miliband spoke at a large “March for the Alternative” rally held in London on 26 March 2011 to protest against cuts to public spending, though he was criticised by some for comparing it to the anti-apartheid and American civil rights movements.[47][48][49]

A June 2011 poll result from Ipsos MORI put Labour 2 percentage points ahead of the Conservatives, but Miliband’s personal rating was low, being rated as less popular than Iain Duncan Smith at a similar stage in his leadership.[50]The same organisation’s polling did find that Miliband’s personal ratings in his first full year of leadership were better than David Cameron‘s during his first full year as Conservative leader in 2006.[51]

In July 2011, following the revelation that the News of the World had paid private investigators to hack into the phones of Milly Dowler, as well as the families of murder victims and deceased servicemen, Miliband called for News International chief executive Rebekah Brooks to resign, urged David Cameron to establish a public, judge-led inquiry into the scandal, and announced that he would force a Commons vote on whether to block the News International bid for a controlling stake in BSkyB. He also called for the Press Complaints Commission to be abolished – a call later echoed by Cameron and Nick Clegg – and called into question Cameron’s judgement in hiring former News of the World editor Andy Coulson to be his Director of communications.[52] Cameron later took the unusual step of saying that the government would back Miliband’s motion that the BSkyB bid be dropped, and an hour before Miliband’s motion was due to be debated, News International announced that it would withdraw the bid.[53][54]

Following the riots in England in August 2011, Miliband called for a public inquiry into the events, and insisted society had “to avoid simplistic answers”. The call for an inquiry was rejected by David Cameron, prompting Miliband to say he would set up his own. In a BBC Radio 4 interview shortly after the riots, Miliband spoke of an irresponsibility that applied not only to the people involved in the riots, but “wherever we find it in our society. We’ve seen in the past few years…MPs’ expenses, what happened in the banks”. Miliband also said Labour did not do enough to tackle moral problems during its 13 years in office.[55] In December 2011 Miliband appointed Tim Livesey, a former adviser to the Archbishop of Canterbury, to be his full-time chief of staff.[56]

In his first speech of 2012, Miliband said that if Labour won the 2015 general election the times would be difficult economically, but Labour was still the only party capable of delivering “fairness”. He also said he would tackle “vested interests”, citing energy and rail companies.[57] Following the announcement in late January 2012 that the chief executive officer of nationalised The Royal Bank of Scotland, Stephen Hester, would receive a bonus worth £950,000, Miliband called the amount “disgraceful”, and urged David Cameron to act to prevent the bonus. Cameron refused, saying it was a matter for the RBS board, leading Miliband to announce that Labour would force a Commons vote on whether or not the government should block it. Hester announced that he would forego his bonus, and Miliband said Labour would carry on with a Commons vote regardless, focusing instead on the bonuses of other RBS executives.[58][59] Following George Galloway’s unexpected win in the March by-election in Bradford West, Miliband announced he would lead an inquiry into the result, saying, it “could not be dismissed as a one-off”.[60] In April 2012, in the midst of a debate about the nature of political party funding, Miliband called on David Cameron to institute a £5,000 cap on donations from individuals and organisations to political parties, after it had been suggested that the government favoured a cap of £50,000.[61] On 14 July 2012, Miliband became the first Leader of the Labour Party to attend and address the Durham Miners’ Gala in 23 years.[62] In the same month, Miliband became the first British politician to be invited to France to meet the new French President, François Hollande.[63]

On 23 January 2013, Miliband stated that he was against holding a referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union because of the economic uncertainty that it would create.[64] On 18 March 2013, Miliband reached a deal with both Cameron and Nick Clegg on new press regulation laws following the Leveson Inquiry, which he said “satisfied the demands of protection for victims and freedom of the press”.[65] In August 2013, following the recall of Parliament to discuss analleged chemical attack in Syria, Miliband announced that Labour would oppose any military intervention on the basis that there was insufficient evidence.[66] David Cameron had been in favour of such action but lost the ensuing vote, making it the first time that a British prime minister had been prevented from instigating military action by parliament since 1956.[66]

At the Labour conference in September 2013, Miliband highlighted his party’s stance on the NHS and announced if elected Labour would abolish the bedroom tax. The conference included several ‘signature’ policies, such as strengthening theminimum wage, freezing business rates, building 200,000 houses a year, lowering the voting age to 16, and the provision of childcare by primary schools between 8am and 6pm. The policy that attracted the most attention was the commitment to help tackle the ‘cost-of-living crisis’ by freezing gas and electricity prices until 2017 to give time to ‘reset the market’ in favour of consumers.[67] In January 2014 Miliband extended the concept of reform to include the ‘big five’ banks, in addition to the ‘big six’ utility companies, and discussed the impact of the cost-of-living on the ‘squeezed middle’ saying “the current cost-of-living crisis is not just about people on tax credits, zero-hour contracts and the minimum wage. It is about the millions of middle-class families who never dreamt that life would be such a struggle”.[68]

Throughout 2014, Miliband changed Labour’s policy on immigration, partly in response to UKIP‘s performance in the European and local elections in May, and the close result in the Heywood and Middleton by-election in October. Miliband committed to increase funding for border checks, tackle exploitation and the undercutting of wages, require employers who recruit abroad to create apprenticeships, and ensure workers in public-facing roles have minimum standards of English. In November 2014, Labour announced plans to require new EU migrants wait two years before claiming benefits.[69][70]

Miliband campaigned in the Scottish independence referendum with the cross-party Better Together campaign, supportingScotland‘s membership of the United Kingdom. Opinion polls showed solid leads for the ‘no’ campaign, with a 20 point-lead on 19 August. However, by the end of the month, the lead has fallen to just 6 points, with YouGov analysis showing a big shift in support among Labour supporters. Miliband made an unplanned visit to Lanarkshire to draw a contrast between a Labour and Conservative future for Scotland within the UK.[71] A poll on 7 September showed a 2-point lead for the ‘yes’ campaign, leading to a joint commitment by Miliband, Cameron and Clegg for greater devolution to Scotland through a version of home rule.[72] The results on 19 September showed victory for the ‘no’ campaign, 55.3% to 44.7%.[73]

The day after the referendum, Cameron raised the issue of ‘English votes for English laws’, with Miliband criticising the move as a simplistic solution to a complex problem, eventually coming out in favour for a constitutional convention to be held after the general election.[74][75]

The Labour party conference in Manchester on 21–24 September occurred days after the Scottish referendum result. Miliband’s conference speech was criticised, particularly after he missed sections on the deficit and immigration, after attempting to deliver the speech without notes.[76] At the conference, Miliband pledged to focus on six national goals for Britain until 2025, including boosting pay, apprenticeships and housing; a mansion tax and levy on tobacco companies to fund £2.5 billion a year ‘time to care’ fund for the NHS; a commitment to raise the minimum wage to £8 or more by 2020; and a promise to lower the voting age to 16 ready for elections in 2016.[77][78]

In February 2015, Labour pledged to reverse the privatisation of the railways by getting rid of the franchising system, after previously saying that they would allow the public sector to bid for franchises.[79]

Shadow Cabinet[edit]

The first election to the Shadow Cabinet that took place under Miliband’s leadership was on 7 October 2010. Ending days of speculation, David Miliband announced that he would not seek election to the Shadow Cabinet on 29 September, the day nominations closed, saying he wanted to avoid “constant comparison” with his brother Ed.[80] The three other defeated candidates for the Labour leadership all stood in the election, though Diane Abbott failed to win enough votes to gain a place. Following the election, Miliband unveiled his Shadow Cabinet on 8 October 2010. Among others he appointed Alan Johnson as Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, Yvette Cooper was chosen as Shadow Foreign Secretary, and both defeated Labour leadership candidates Ed Balls and Andy Burnham were given senior roles, becoming Shadow Home Secretary and Shadow Education Secretary respectively. Burnham was also given responsibility for overseeing Labour’s election co-ordination. Sadiq Khan, who managed Miliband’s successful leadership campaign, was appointed Shadow Justice Secretary and Shadow Lord Chancellor, and continuing Deputy Leader Harriet Harman continued to shadow Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, as well as being made Shadow International Development Secretary.[81] Alan Johnson would later resign, stepping down for “personal reasons” on 20 January 2011, necessitating Miliband’s first reshuffle, in which he made Balls Shadow Chancellor, Cooper Shadow Home Secretary and Douglas Alexander Shadow Foreign Secretary.[82]

On 24 June 2011, it was reported that Miliband was seeking to change the decades-old rule that Labour’s Shadow Cabinet would be elected every two years, instead wanting to adopt a system where he alone had the authority to select its members. Miliband later confirmed the story, claiming that the rule represented “a legacy of Labour’s past in opposition”.[83]On 5 July, Labour MPs voted overwhelmingly by a margin of 196 to 41 to back the rule change, paving the way for NEC andconference approval, which was secured in September 2011.[84][85] This made Miliband the first Labour leader to have the authority to pick his own Shadow Cabinet.[86] ` On 7 October 2011, Miliband reshuffled his Shadow Cabinet. John Denham,John Healey and Shaun Woodward announced that they were stepping down, while Meg Hillier, Ann McKechin andBaroness Scotland also left the Shadow Cabinet. Veteran MPs Tom Watson, Jon Trickett, Stephen Twigg and Vernon Coaker were promoted to the Shadow Cabinet, as were several of the 2010 intake, including Chuka Umunna, Margaret Curran and Rachel Reeves, with Liz Kendall and Michael Dugher given the right to attend Shadow Cabinet. Lord Wood andEmily Thornberry were also made Shadow Cabinet attendees.[87]

On 15 May 2012, Miliband appointed Owen Smith to replace Peter Hain – who retired from frontline politics – as Shadow Welsh Secretary, and also promoted Jon Cruddas to the Shadow Cabinet, putting him in charge of overseeing Labour’s ongoing policy review with a view to draft Labour’s manifesto for the next election.[88] On 4 July 2013, Miliband effectively sacked Tom Watson from the Shadow Cabinet after allegations of corruption over the selection of a Parliamentary candidate for Falkirk. Watson had offered his resignation, but when Miliband was asked by a journalist specifically whether he had sacked Watson, he replied, “…I said it was right for him to go, yes.”[89]

On 7 October 2013, Miliband reshuffled his Shadow Cabinet for the third time, saying that this would be the last reshuffle before the general election.[90] In a move similar to his 2011 reshuffle, several MPs from the 2010 intake were promoted, while more long-serving MPs were moved. Tristram Hunt and Rachel Reeves received promotions, while Liam Byrne and Stephen Twigg were among those demoted.[90]

Miliband conducted a final mini-reshuffle ahead of the 2015 general election in November 2014, when Jim Murphy resigned as Shadow International Development Secretary to become Leader of the Scottish Labour Party.

Local and European elections[edit]

Miliband’s first electoral tests as Labour Leader came in the elections to theScottish Parliament, Welsh Assembly and various councils across England, excluding London, on 5 May 2011. The results for Labour were described as a “mixed bag”, with the party performing well in Wales – falling just one seat short of an overall majority and forming the next Welsh Government on its own – and making large gains from the Liberal Democrats in northern councils, includingSheffield, Leeds, Liverpool and Manchester. Results were less encouraging in the south of England, and results in Scotland were described as a “disaster”, with Labour losing nine seats to the SNP, which went on to gain the Parliament’s first ever majority.[91] Miliband said that following the poor showings in Scotland “lessons must still be learnt”.[91][92]

Miliband launched Labour’s campaign for the 2012 local elections with a speech in Birmingham, accusing the coalition government of “betrayal”, and claiming that it “lacked the values” that Britain needed.[93] The Labour results were described as a success, with the party building on its performance the previous year in the north of England and Wales, consolidating its position in northern cities and winning control of places such as Cardiffand Swansea.[94] Labour performed well in the Midlands and South of England, winning control of councils including Birmingham, Norwich, Plymouth and Southampton.[94] Labour was less successful in Scotland than England and Wales, but retained control of Glasgow despite predictions it would not.[94] Overall, Labour gained over 800 councillors and control of 22 councils.[94]

In April 2013, Miliband pledged ahead of the upcoming county elections that Labour would change planning laws to give local authorities greater authority to decide what shops can open in their high streets. He also said that Labour would introduce more strenuous laws relating to pay-day lenders and betting shops.[95] Labour subsequently gained nearly 300 councillors, as well as control of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire County Councils.[96][97][98]

In May 2014, Miliband led Labour through the European Parliament elections, where the party increased its number ofMembers of the European Parliament from 13 to 20. Labour came second with 24.4% of the vote, finishing ahead of the Conservatives but behind the UK Independence Party. This was the first time since the European elections of 1984 that the largest opposition party had failed to win the most seats.[99] On the same day, Labour polled ahead of all other parties at the local elections, winning 31% of the vote and taking control of six additional councils.

2015 general election and resignation[edit]

On 30 March 2015, the Parliament of the United Kingdom dissolved and a general election was called for 7 May. Miliband began his campaign by launching a “manifesto for business”, stating that only by voting Labour would the UK’s position within the European Union be secure.[100] Miliband subsequently unveiled five pledges at a rally in Birmingham which would form the focus of a future Labour government, specifically identifying policies on deficit reduction, living standards, the NHS, immigration controls and tuition fees. He included an additional pledge on housing and rent on 27 April.[101][102]On 14 April, Labour launched its full manifesto, which Miliband said was fully funded and would require no additional borrowing.[103] Also in April, he claimed he would attempt to create legislation against Islamophobia.[104]

Throughout the campaign for the 7 May elections, Miliband insisted that David Cameron should debate him one on one as part of a televised election broadcast [105] in order to highlight differences in policies between the two major parties, but this was never to happen, with the pair instead being interviewed separately by Jeremy Paxman as part of the first major televised political broadcast of the election involving multiple parties.

Despite opinion polls leading up to the general election predicting a tight result, Labour decisively lost the 7 May general election to the Conservatives. Although gaining 22 seats, Labour lost all but one of its MPs in Scotland and ended up with a net loss of 48 seats, failing to win a number of key marginal seats that it had expected to win comfortably. After being returned as MP for Doncaster North, Miliband stated that it had been a “difficult and disappointing” night for Labour.[106][107][108] Following David Cameron’s success in forming a majority government, Miliband resigned as Leader of the Labour Party on 8 May, with Harriet Harman becoming acting leader while a leadership election was initiated.[109][110]

Policies and views[edit]

Self-described views[edit]

Miliband described himself as a new type of Labour politician, looking to move beyond the divisiveness of Blairism andBrownism, and calling for an end to the “factionalism and psychodramas” of Labour’s past. He also repeatedly spoke of the requirement for a “new politics”.[111]

During the Labour leadership campaign, he described himself as a socialist, and spoke out against some of the actions of the Blair ministry, including criticising its record on civil liberties and foreign policy.[112] Though he was not an MP at the time of the 2003 vote, Miliband was a strong critic of the Iraq War.[112][113] He backed UK military action and intervention inAfghanistan and Libya respectively.

Miliband called for “responsible capitalism” when Google‘s Eric Schmidt commented on his corporation’s non-payment of tax.[114] He also supported making the UK’s 50% top rate of tax permanent, as well as the institution of a new financial transaction tax, mutualising Northern Rock, putting limits on top salaries, scrapping tuition fees in favour of a graduate tax, implementing a living wage policy and the scrapping of the ID cards policy, and spoke in favour of a “National Care Service”.[115][116]

Miliband worked closely with the think tank Policy Network on the concept of predistribution as a means to tackle what he described as ‘the growing crisis in living standards’.[117] His announcement that predistribution would become a cornerstone of the UK Labour Party’s economic policy was jokingly mocked by Prime Minister David Cameron during Prime Minister’s Questions in the House of Commons.[118]

Though Labour remained officially neutral, he in a personal capacity supported the ultimately unsuccessful “Yes to AV” campaign in the Alternative Vote referendum on 5 May 2011, saying that it would benefit Britain’s “progressive majority”.[119][120] In September 2011, Miliband stated that a future Labour Government would immediately cut the cap on tuition fees for university students from £9,000 per year to £6,000, though he also stated that he remained committed to a graduate tax in the long-run.[121] Together with Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls, Miliband also promoted a “five-point plan for jobs and growth” aimed at helping the UK economy, involving extending the bonus tax on banks pioneered by Alistair Darling, bringing forward planned long-term investment to help reduce unemployment, cutting the rate of VAT from 20% back to 17.5%, cutting VAT on home improvements to 5% for a temporary one-year period, and instigating a one-yearNational Insurance break to encourage employers to hire more staff.[122] Miliband also endorsed the Blue Labour trend in the Labour Party, founded by Maurice Glasman. Blue Labour talks about family and friendships at the heart of society, rather than just material wealth; it also offers a very strong critique of the free market as well as the big state. This was seen to have influenced his 2011 conference speech, signalling “predatory and productive capitalism”.[123][124]

Miliband is progressive in regard to issues of gender and sexuality. He publicly identifies as a feminist.[125] March 2012 Miliband pledged his support for same sex marriage. As he signed an ‘equal marriage pledge’, he said, “I strongly agree gay and lesbian couples should have an equal right to marry and deserve the same recognition from the state and society as anyone else.”[126]

In June 2014, while speaking to the Labour Friends of Israel, Miliband stated that if he became Prime Minister he would seek “closer ties” with Israel and opposed the boycott of Israeli goods, saying that he would “resolutely oppose the isolation of Israel” and that nobody in the Labour Party should question Israel’s right to exist.[127][128] He also stated that as a Jew and a friend of Israel, he must also criticise Israel when necessary, opposing the “killing of innocent Palestinian civilians” and calling Hamas a terrorist organisation.[129]

Comments on other politicians[edit]

Miliband with his wife Justine at the 2011 Labour Party Conference

Miliband has criticised Conservative Leader and Prime Minister David Cameron for “sacrificing everything on the altar of deficit reduction”, and has accused him of being guilty of practising “old politics”, citing alleged broken promises on areas such as crime, policing, bank bonuses, and child benefit.[130]

Miliband has also been particularly critical of Liberal Democrat Leader and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg following the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreement, accusing him of “betrayal” and of “selling-out” his party’s voters. He has also stated that he would demand the resignation of Nick Clegg as a precursor to any future Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition.[131] In the 2011 Alternative Vote referendum, Miliband refused to share a platform with Clegg, stating that he had become “too toxic” a brand, and that he would harm the “Yes to AV” campaign. He shared platforms during the campaign with former Liberal Democrat Leaders Lord Ashdown and Charles Kennedy, as well as current Liberal Democrat Deputy Leader Simon Hughes, the Green Party Leader Caroline Lucas and Business Secretary Vince Cable, among others.[132] Since becoming Labour leader, Miliband has made speeches aimed at winning over disaffected Liberal Democrats, identifying a difference between the “Orange Book” Lib Dems, who were closer to the Conservatives, and Lib Dems on the centre-left, offering the latter a role in helping Labour’s policy review.[130]

Following the death of former Prime Minister and Conservative Leader Margaret Thatcher in 2013, Miliband spoke in a House of Commons sitting specially convened to pay tributes to her. He noted that, although he disagreed with a few of her policies, he respected “what her death means to the many, many people who admired her”. He also said that Thatcher “broke the mould” in everything she had achieved in her life, and that she had had the ability to “overcome every obstacle in her path”.[133] He had previously praised Thatcher shortly before the Labour Party Conference in September 2012 for creating an “era of aspiration” in the 1980s.[134]

Miliband has previously spoken positively of his brother David, praising his record as Foreign Secretary, and saying that “his door was always open” following David’s decision not to stand for the Shadow Cabinet in 2010.[135] Upon David’s announcement in 2013 that he would resign as a Labour MP and move to New York to head the International Rescue Committee, Miliband said that British politics would be “a poorer place” without him, and that he thought David “would once again make a contribution to British public life.”[136]

When asked to choose the greatest British Prime Minister, Miliband answered with Labour’s post-war Prime Minister and longest-serving Leader, Clement Attlee.[137] He has also spoken positively of his two immediate predecessors as Labour leader, former Prime Ministers Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, praising their leadership and records in government.[138]

Media portrayal[edit]

Miliband was portrayed during Labour’s 2015 election campaign as being genuine in his desire to improve the lives of working people and to display progression from New Labour, but unable to defeat interpretations of him as being ineffectual, or even cartoonish in nature. Political illustrators perceived a resemblance to Wallace of the British animationWallace and Gromit and greatly exaggerated this in caricatures; various images also surfaced of Miliband performing tasks such as eating a sandwich, donating money to a beggar, smiling, and giving a kiss to his wife, all while displaying apparently unnatural or awkward facial expressions. In a March 2015 Newsnight election debate, he was challenged by Jeremy Paxman as to whether or not he was ‘tough enough’ to be Prime Minister, famously responding, “Hell yes, I’m tough enough,” in reference to his reluctance to support air strikes against extremist targets in Syria.[139]

Personal life[edit]

Miliband is married to a barrister, Justine Thornton.[140] The pair met in 2002 and lived together in North London before becoming engaged in March 2010 and married in May 2011.[141][142][143] They have two sons, Daniel, born 2009, and Samuel, born 2010.[144][145]

Miliband is of Jewish heritage—the first Jewish leader of the Labour Party[146][147]—and describes himself as a Jewish atheist.[148][149] After marrying Thornton in a civil ceremony on 27 May 2011, he paid tribute to his Jewish heritage by following the tradition of breaking a glass.[150][151] In 2012, Miliband wrote, “Like many others from Holocaust families, I have a paradoxical relationship with this history. On one level I feel intimately connected with it – this happened to my parents and grandparents. On another, it feels like a totally different world.”[152]

Labour (UK)

|

Labour Party

|

|

|---|---|

| Leader | Jeremy Corbyn MP |

| Deputy Leader | Tom Watson MP |

| General Secretary | Iain McNicol |

| Founded | 27 February 1900[1][2] |

| Headquarters | Labour Central Kings Manor Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 6PA |

| Student wing | Labour Students |

| Youth wing | Young Labour |

| Membership (2016) | |

| Ideology | Social democracy Democratic socialism |

| Political position | Centre-left |

| European affiliation | Party of European Socialists |

| International affiliation | Progressive Alliance, Socialist International(observer) |

| European Parliament group | Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats |

| Colours | Red |

| House of Commons |

229 / 650

|

| House of Lords |

210 / 800

|

| European Parliament |

20 / 73

|

| Scottish Parliament |

24 / 129

|

| Welsh Assembly |

29 / 60

|

| London Assembly |

12 / 25

|

| Local government |

6,885 / 20,565

|

| Police & Crime Commissioners |

15 / 40

|

| Directly-elected Mayors |

13 / 17

|

| Website | |

| www.labour.org.uk | |

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labour |

|---|

|

The Labour Party is a centre-left political party in the United Kingdom.[4][5][6][7]Growing out of the trade union movement and socialist parties of the nineteenth century, the Labour Party has been described as a “broad church“, encompassing a diversity of ideological trends from strongly socialist to moderately social democratic.

Founded in 1900, the Labour Party overtook the Liberal Party as the main opposition to the Conservative Party in the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and from 1929 to 1931. Labour later served in the wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after which it formed a majority government under Clement Attlee. Labour was also in government from 1964 to 1970 under Harold Wilson and from 1974 to 1979, first under Wilson and then James Callaghan.

The Labour Party was last in government from 1997 to 2010 under Tony Blairand Gordon Brown, beginning with a landslide majority of 179, reduced to 167 in 2001 and 66 in 2005. Having won 232 seats in the 2015 general election, the party is the Official Opposition in the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Labour is the largest party in the Welsh Assembly, the third largest party in theScottish Parliament and has twenty MEPs in the European Parliament, sitting in the Socialists and Democrats Group. The party also organises in Northern Ireland, but does not contest elections to the Northern Ireland Assembly. The Labour Party is a full member of the Party of European Socialists andProgressive Alliance, and holds observer status in the Socialist International. In September 2015, Jeremy Corbyn was elected Leader of the Labour Party.

History

Founding

The Labour Party’s origins lie in the late 19th century, when it became apparent that there was a need for a new political party to represent the interests and needs of the urban proletariat, a demographic which had increased in number and had recently been given franchise.[8] Some members of the trades union movement became interested in moving into the political field, and after further extensions of the voting franchise in 1867 and 1885, the Liberal Party endorsed some trade-union sponsored candidates. The first Lib–Lab candidate to stand was George Odger in the Southwark by-election of 1870. In addition, several small socialist groups had formed around this time, with the intention of linking the movement to political policies. Among these were the Independent Labour Party, the intellectual and largely middle-class Fabian Society, the Marxist Social Democratic Federation[9] and the Scottish Labour Party.

In the 1895 general election, the Independent Labour Party put up 28 candidates but won only 44,325 votes. Keir Hardie, the leader of the party, believed that to obtain success in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to join with other left-wing groups. Hardie’s roots as a lay preacher contributed to an ethos in the party which led to the comment by 1950s General Secretary Morgan Phillips that “Socialism in Britain owed more to Methodism than Marx”.[10]

Labour Representation Committee

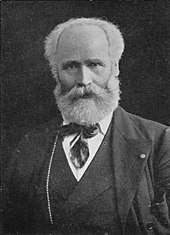

Keir Hardie, one of the Labour Party’s founders and its first leader

In 1899, a Doncaster member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, Thomas R. Steels, proposed in his union branch that the Trade Union Congress call a special conference to bring together all left-wing organisations and form them into a single body that would sponsor Parliamentary candidates. The motion was passed at all stages by the TUC, and the proposed conference was held at the Memorial Hall on Farringdon Street on 26 and 27 February 1900. The meeting was attended by a broad spectrum of working-class and left-wing organisations—trades unions represented about one third of the membership of the TUC delegates.[11]

After a debate, the 129 delegates passed Hardie’s motion to establish “a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour.”[12] This created an association called the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), meant to coordinate attempts to support MPs sponsored by trade unions and represent the working-class population.[2] It had no single leader, and in the absence of one, the Independent Labour Party nominee Ramsay MacDonald was elected as Secretary. He had the difficult task of keeping the various strands of opinions in the LRC united. The October 1900 “Khaki election” came too soon for the new party to campaign effectively; total expenses for the election only came to £33.[13] Only 15 candidatures were sponsored, but two were successful; Keir Hardie in Merthyr Tydfil and Richard Bell in Derby.[14]

Support for the LRC was boosted by the 1901 Taff Vale Case, a dispute between strikers and a railway company that ended with the union being ordered to pay £23,000 damages for a strike. The judgement effectively made strikes illegal since employers could recoup the cost of lost business from the unions. The apparent acquiescence of the Conservative Government of Arthur Balfour to industrial and business interests (traditionally the allies of the Liberal Party in opposition to the Conservative’s landed interests) intensified support for the LRC against a government that appeared to have little concern for the industrial proletariat and its problems.[14]

In the 1906 election, the LRC won 29 seats—helped by a secret 1903 pact betweenRamsay MacDonald and Liberal Chief Whip Herbert Gladstone that aimed to avoid splitting the opposition vote between Labour and Liberal candidates in the interest of removing the Conservatives from office.[14]

In their first meeting after the election the group’s Members of Parliament decided to adopt the name “The Labour Party” formally (15 February 1906). Keir Hardie, who had taken a leading role in getting the party established, was elected as Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party (in effect, the Leader), although only by one vote over David Shackleton after several ballots. In the party’s early years the Independent Labour Party (ILP) provided much of its activist base as the party did not have individual membership until 1918 but operated as a conglomerate of affiliated bodies. The Fabian Society provided much of the intellectual stimulus for the party. One of the first acts of the new Liberal Government was to reverse the Taff Vale judgement.[14]

The People’s History Museum in Manchester holds the minutes of the first Labour Party meeting in 1906 and has them on display in the Main Galleries.[15] Also within the museum is the Labour History Archive and Study Centre, which holds the collection of the Labour Party, with material ranging from 1900 to the present day.[16]

Early years

The 1910 election saw 42 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons, a significant victory since, a year before the election, the House of Lords had passed the Osborne judgment ruling that Trades Unions in the United Kingdom could no longer donate money to fund the election campaigns and wages of Labour MPs. The governing Liberals were unwilling to repeal this judicial decision with primary legislation. The height of Liberal compromise was to introduce a wage for Members of Parliament to remove the need to involve the Trade Unions. By 1913, faced with the opposition of the largest Trades Unions, the Liberal government passed the Trade Disputes Act to allow Trade Unions to fund Labour MPs once more.

During the First World War the Labour Party split between supporters and opponents of the conflict but opposition to the war grew within the party as time went on. Ramsay MacDonald, a notable anti-war campaigner, resigned as leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party and Arthur Henderson became the main figure of authority within the party. He was soon accepted into Prime Minister Asquith‘s war cabinet, becoming the first Labour Party member to serve in government.

Despite mainstream Labour Party’s support for the coalition the Independent Labour Party was instrumental in opposing conscription through organisations such as the Non-Conscription Fellowship while a Labour Party affiliate, the British Socialist Party, organised a number of unofficial strikes.[citation needed]

Arthur Henderson resigned from the Cabinet in 1917 amid calls for party unity to be replaced by George Barnes. The growth in Labour’s local activist base and organisation was reflected in the elections following the war, the co-operativemovement now providing its own resources to the Co-operative Party after the armistice. The Co-operative Party later reached an electoral agreement with the Labour Party.

With the Representation of the People Act 1918, almost all adult men (excepting only peers, criminals and lunatics) and most women over the age of thirty were given the right to vote, almost tripling the British electorate at a stroke, from 7.7 million in 1912 to 21.4 million in 1918. This set the scene for a surge in Labour representation in parliament.[17]

The Communist Party of Great Britain was refused affiliation to the Labour Party between 1921 and 1923.[18] Meanwhile, the Liberal Party declined rapidly, and the party also suffered a catastrophic split which allowed the Labour Party to gain much of the Liberals’ support. With the Liberals thus in disarray, Labour won 142 seats in 1922, making it the second largest political group in the House of Commons and the official opposition to the Conservative government. After the election the now-rehabilitated Ramsay MacDonald was voted the first official leader of the Labour Party.

First Labour government, 1924

Ramsay MacDonald: First Labour Prime Minister, 1924 and 1929–31

The 1923 general election was fought on the Conservatives’ protectionist proposals but, although they got the most votes and remained the largest party, they lost their majority in parliament, necessitating the formation of a government supporting free trade. Thus, with the acquiescence of Asquith’s Liberals, Ramsay MacDonald became the first ever Labour Prime Minister in January 1924, forming the first Labour government, despite Labour only having 191 MPs (less than a third of the House of Commons).

Because the government had to rely on the support of the Liberals it was unable to get any socialist legislation passed by the House of Commons. The only significant measure was the Wheatley Housing Act, which began a building programme of 500,000 homes for rental to working-class families. Legislation on education, unemployment and social insurance were also passed.

While there were no major labour strikes during his term, MacDonald acted swiftly to end those that did erupt. When the Labour Party executive criticized the government, he replied that, “public doles, Poplarism [local defiance of the national government], strikes for increased wages, limitation of output, not only are not Socialism, but may mislead the spirit and policy of the Socialist movement.”[19]

The government collapsed after only nine months when the Liberals voted for a Select Committee inquiry into the Campbell Case, a vote which MacDonald had declared to be a vote of confidence. The ensuing 1924 general election saw the publication, four days before polling day, of the Zinoviev letter, in which Moscow talked about a Communist revolution in Britain. The letter had little impact on the Labour vote—which held up. It was the collapse of the Liberal party that led to the Conservative landslide. The Conservatives were returned to power although Labour increased its vote from 30.7% to a third of the popular vote, most Conservative gains being at the expense of the Liberals. However many Labourites for years blamed their defeat on foul play (the Zinoviev Letter), thereby according to A. J. P. Taylor misunderstanding the political forces at work and delaying needed reforms in the party.[20][21]

In opposition MacDonald continued his policy of presenting the Labour Party as a moderate force. During the General Strike of 1926 the party opposed the general strike, arguing that the best way to achieve social reforms was through the ballot box. The leaders were also fearful of Communist influence orchestrated from Moscow.[22]

Second Labour government, 1929–1931

In the 1929 general election, the Labour Party became the largest in the House of Commons for the first time, with 287 seats and 37.1% of the popular vote. However MacDonald was still reliant on Liberal support to form a minority government. MacDonald went on to appoint Britain’s first female cabinet minister, Margaret Bondfield, who was appointed Minister of Labour.

The government, however, soon found itself engulfed in crisis: the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and eventual Great Depression occurred soon after the government came to power, and the crisis hit Britain hard. By the end of 1930 unemployment had doubled to over two and a half million.[23] The government had no effective answers to the crisis. By the summer of 1931 a dispute over whether or not to reduce public spending had split the government.

As the economic situation worsened MacDonald agreed to form a “National Government” with the Conservatives and theLiberals. On 24 August 1931 MacDonald submitted the resignation of his ministers and led a small number of his senior colleagues in forming the National Government together with the other parties. This caused great anger among those within the Labour Party who felt betrayed by MacDonald’s actions: he and his supporters were promptly expelled from the Labour Party and formed a separate National Labour Organisation. The remaining Labour Party MPs (led again by Arthur Henderson) and a few Liberals went into opposition. The ensuing 1931 general election resulted in overwhelming victory for the National Government and disaster for the Labour Party which won only 52 seats, 225 fewer than in 1929.

1930s split

Arthur Henderson, elected in 1931 to succeed MacDonald, lost his seat in the 1931 general election. The only former Labour cabinet member who had retained his seat, the pacifist George Lansbury, accordingly became party leader.

The party experienced another split in 1932 when the Independent Labour Party, which for some years had been increasingly at odds with the Labour leadership, opted to disaffiliate from the Labour Party and embarked on a long, drawn-out decline.

Lansbury resigned as leader in 1935 after public disagreements over foreign policy. He was promptly replaced as leader by his deputy, Clement Attlee, who would lead the party for two decades. The party experienced a revival in the 1935 general election, winning 154 seats and 38% of the popular vote, the highest that Labour had achieved.

As the threat from Nazi Germany increased, in the late 1930s the Labour Party gradually abandoned its pacifist stance and supported re-armament, largely due to the efforts of Ernest Bevin and Hugh Dalton who by 1937 had also persuaded the party to oppose Neville Chamberlain‘s policy of appeasement.[23]

Wartime coalition, 1940–1945

The party returned to government in 1940 as part of the wartime coalition. When Neville Chamberlain resigned in the spring of 1940, incoming Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to bring the other main parties into a coalition similar to that of the First World War. Clement Attlee was appointed Lord Privy Seal and a member of the war cabinet, eventually becoming the United Kingdom’s first Deputy Prime Minister.

A number of other senior Labour figures also took up senior positions: the trade union leader Ernest Bevin, as Minister of Labour, directed Britain’s wartime economy and allocation of manpower, the veteran Labour statesman Herbert Morrisonbecame Home Secretary, Hugh Dalton was Minister of Economic Warfare and later President of the Board of Trade, whileA. V. Alexander resumed the role he had held in the previous Labour Government as First Lord of the Admiralty.

Attlee government, 1945–1951

Clement Attlee: Labour Prime Minister, 1945–51

At the end of the war in Europe, in May 1945, Labour resolved not to repeat the Liberals’ error of 1918, and promptly withdrew from government, on trade union insistence, to contest the 1945 general election in opposition to Churchill’s Conservatives. Surprising many observers,[24] Labour won a formidable victory, winning just under 50% of the vote with a majority of 159 seats.[25]

Although Clement Attlee was no great radical himself,[26] Attlee’s government proved one of the most radical British governments of the 20th century, enacting Keynesian economic policies, presiding over a policy of nationalising major industries and utilities including theBank of England, coal mining, the steel industry, electricity, gas, and inland transport (including railways, road haulage and canals). It developed and implemented the “cradle to grave” welfare state conceived by the economist William Beveridge.[27][28][29] To this day, most people in the United Kingdom see the 1948 creation of Britain’s publicly fundedNational Health Service (NHS) under health minister Aneurin Bevan as Labour’s proudest achievement.[30] Attlee’s government also began the process of dismantling the British Empire when it granted independence to India and Pakistan in 1947, followed by Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) the following year. At a secret meeting in January 1947, Attlee and six cabinet ministers, including Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, decided to proceed with the development of Britain’s nuclear weapons programme,[23] in opposition to the pacifist and anti-nuclear stances of a large element inside the Labour Party.

Labour went on to win the 1950 general election, but with a much reduced majority of five seats. Soon afterwards, defence became a divisive issue within the party, especially defence spending (which reached a peak of 14% of GDP in 1951 during the Korean War),[31] straining public finances and forcing savings elsewhere. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Hugh Gaitskell, introduced charges for NHS dentures and spectacles, causing Bevan, along with Harold Wilson (then President of the Board of Trade), to resign over the dilution of the principle of free treatment on which the NHS had been established.

In the 1951 general election, Labour narrowly lost to Churchill’s Conservatives, despite receiving the larger share of the popular vote – its highest ever vote numerically. Most of the changes introduced by the 1945–51 Labour government were accepted by the Conservatives and became part of the “post-war consensus” that lasted until the late 1970s. Food and clothing rationing, however, still in place since the war, were swiftly relaxed, then abandoned from about 1953.

Post-war consensus, 1951–1964

Following the defeat of 1951 the party spent 13 years in opposition. The party suffered an ideological split, while the postwar economic recovery and the social effects of Attlee’s reforms made the public broadly content with the Conservative governments of the time. Attlee remained as leader until his retirement in 1955.

His replacement, Hugh Gaitskell, associated with the right wing of the party, struggled in dealing with internal party divisions (particularly over Clause IV of the Labour Party Constitution, which was viewed as Labour’s commitment to nationalisationand Gaitskell wanted scrapped[32]) in the late 1950s and early 1960s and Labour lost the 1959 general election. In 1963, Gaitskell’s sudden death from a heart attack made way for Harold Wilson to lead the party.

Wilson government, 1964–1970

Harold Wilson: Labour Prime Minister, 1964–70 and 1974–76

A downturn in the economy and a series of scandals in the early 1960s (the most notorious being the Profumo affair) had engulfed the Conservative government by 1963. The Labour Party returned to government with a 4-seat majority under Wilson in the 1964 general election but increased its majority to 96 in the 1966 general election.

Wilson’s government was responsible for a number of sweeping social and educational reforms under the leadership of Home Secretary Roy Jenkins such as the abolishment of the death penalty in 1964, the legalisation of abortion and homosexuality (initially only for men aged 21 or over, and only in England and Wales) in 1967 and the abolition of theatre censorship in 1968. Comprehensive education was expanded and the Open Universitycreated. However Wilson’s government had inherited a large trade deficit that led to a currency crisis and ultimately a doomed attempt to stave off devaluation of the pound. Labour went on to lose the 1970 general election to the Conservatives under Edward Heath.

Spell in opposition, 1970–1974

After losing the 1970 general election, Labour returned to opposition, but retained Harold Wilson as Leader. Heath’s government soon ran into trouble over Northern Ireland and a dispute with miners in 1973 which led to the “three-day week“. The 1970s proved a difficult time to be in government for both the Conservatives and Labour due to the 1973 oil crisis which caused high inflation and a global recession.

The Labour Party was returned to power again under Wilson a few weeks after the February 1974 general election, forming a minority government with the support of the Ulster Unionists. The Conservatives were unable to form a government alone as they had fewer seats despite receiving more votes numerically. It was the first general election since 1924 in which both main parties had received less than 40% of the popular vote and the first of six successive general elections in which Labour failed to reach 40% of the popular vote. In a bid to gain a majority, a second election was soon called for October 1974 in which Labour, still with Harold Wilson as leader, won a slim majority of three, gaining just 18 seats taking its total to 319.

Majority to minority, 1974–1979

For much of its time in office the Labour government struggled with serious economic problems and a precarious majority in the Commons, while the party’s internal dissent over Britain’s membership of the European Economic Community (EEC), which Britain had entered under Edward Heath in 1972, led in 1975 to a national referendum on the issue in which two thirds of the public supported continued membership.

Harold Wilson’s personal popularity remained reasonably high but he unexpectedly resigned as Prime Minister in 1976 citing health reasons, and was replaced by James Callaghan. The Wilson and Callaghan governments of the 1970s tried to control inflation (which reached 23.7% in 1975[33]) by a policy of wage restraint. This was fairly successful, reducing inflation to 7.4% by 1978.[14][33] However it led to increasingly strained relations between the government and the trade unions.

James Callaghan: Labour Prime Minister, 1976–79

Fear of advances by the nationalist parties, particularly in Scotland, led to the suppression of a report from Scottish Office economist Gavin McCrone that suggested that an independent Scotland would be ‘chronically in surplus’.[34] By 1977 by-election losses and defections to the breakaway Scottish Labour Party left Callaghan heading a minority government, forced to trade with smaller parties in order to govern. An arrangement negotiated in 1977 with Liberal leader David Steel, known as the Lib-Lab Pact, ended after one year. Deals were then forged with various small parties including the Scottish National Party and the Welsh nationalist Plaid Cymru, prolonging the life of the government.

The nationalist parties, in turn, demanded devolution to their respective constituent countries in return for their supporting the government. When referendums for Scottish and Welsh devolution were held in March 1979 Welsh devolution was rejected outright while theScottish referendum returned a narrow majority in favour without reaching the required threshold of 40% support. When the Labour government duly refused to push ahead with setting up the proposed Scottish Assembly, the SNP withdrew its support for the government: this finally brought the government down as it triggered a vote of confidence in Callaghan’s government that was lost by a single vote on 28 March 1979, necessitating a general election.

Callaghan had been widely expected to call a general election in the autumn of 1978 when most opinion polls showed Labour to have a narrow lead.[14] However he decided to extend his wage restraint policy for another year hoping that the economy would be in a better shape for a 1979 election. But during the winter of 1978–79 there were widespread strikes among lorry drivers, railway workers, car workers and local government and hospital workers in favour of higher pay-rises that caused significant disruption to everyday life. These events came to be dubbed the “Winter of Discontent“.

In the 1979 general election Labour was heavily defeated by the Conservatives now led by Margaret Thatcher. The number of people voting Labour hardly changed between February 1974 and 1979 but the Conservative Party achieved big increases in support in the Midlands and South of England, benefiting from both a surge in turnout and votes lost by the ailing Liberals.

Internal conflict and opposition, 1979–1997

After its defeat in the 1979 general election the Labour Party underwent a period of internal rivalry between the left represented by Tony Benn, and the right represented by Denis Healey. The election of Michael Foot as leader in 1980, and the leftist policies he espoused, such as unilateral nuclear disarmament, leaving the European Economic Community (EEC) and NATO, closer governmental influence in the banking system, the creation of a national minimum wage and a ban on fox hunting[35] led in 1981 to four former cabinet ministers from the right of the Labour Party (Shirley Williams, William Rodgers,Roy Jenkins and David Owen) forming the Social Democratic Party. Benn was only narrowly defeated by Healey in a bitterly fought deputy leadership election in 1981 after the introduction of an electoral college intended to widen the voting franchise to elect the leader and their deputy. By 1982, the National Executive Committee had concluded that the entryistMilitant tendency group were in contravention of the party’s constitution. The Militant newspaper’s five member editorial board were expelled on 22 February 1983.

The Labour Party was defeated heavily in the 1983 general election, winning only 27.6% of the vote, its lowest share since1918, and receiving only half a million votes more than the SDP-Liberal Alliance who leader Michael Foot condemned for “siphoning” Labour support and enabling the Conservatives to greatly increase their majority of parliamentary seats.[36]

Neil Kinnock, leader of the party in opposition, 1983–92.

Foot resigned and was replaced as leader by Neil Kinnock, with Roy Hattersley as his deputy. The new leadership progressively dropped unpopular policies. The miners strike of 1984–85 over coal mine closures, for which miners’ leader Arthur Scargill was blamed, and the Wapping dispute led to clashes with the left of the party, and negative coverage in most of the press. Tabloid vilification of the so-called loony left continued to taint the parliamentary party by association from the activities of ‘extra-parliamentary’ militants in local government.

The alliances which campaigns such as Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners forged between lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) and labour groups, as well as the Labour Party itself, also proved to be an important turning point in the progression of LGBT issues in the UK.[37] At the 1985 Labour Party conference in Bournemouth, a resolution committing the party to support LGBT equality rights passed for the first time due to block voting support from the National Union of Mineworkers.[37]

Labour improved its performance in 1987, gaining 20 seats and so reducing the Conservative majority from 143 to 102. They were now firmly re-established as the second political party in Britain as the Alliance had once again failed to make a breakthrough with seats. A merger of the SDP and Liberals formed the Liberal Democrats. Following the 1987 election, the National Executive Committee resumed disciplinary action against members of Militant, who remained in the party, leading to further expulsions of their activists and the two MPs who supported the group.

In November 1990 following a contested leadership election, Margaret Thatcher resigned as leader of the Conservative Party and was succeeded as leader and Prime Minister by John Major. Most opinion polls had shown Labour comfortably ahead of the Tories for more than a year before Mrs Thatcher’s resignation, with the fall in Tory support blamed largely on her introduction of the unpopular poll tax, combined with the fact that the economy was sliding into recession at the time.

The change of leader in the Tory government saw a turnaround in support for the Tories, who regularly topped the opinion polls throughout 1991 although Labour regained the lead more than once.

The “yo yo” in the opinion polls continued into 1992, though after November 1990 any Labour lead in the polls was rarely sufficient for a majority. Major resisted Kinnock’s calls for a general election throughout 1991. Kinnock campaigned on the theme “It’s Time for a Change”, urging voters to elect a new government after more than a decade of unbroken Conservative rule. However, the Conservatives themselves had undergone a dramatic change in the change of leader from Thatcher to Major, at least in terms of style if not substance. From the outset, it was clearly a well-received change, as Labour’s 14-point lead in the November 1990 “Poll of Polls” was replaced by an 8% Tory lead a month later.

The 1992 general election was widely tipped to result in a hung parliament or a narrow Labour majority, but in the event the Conservatives were returned to power, though with a much reduced majority of 21.[38] Despite the increased number of seats and votes, it was still an incredibly disappointing result for supporters of the Labour party. For the first time in over 30 years there was serious doubt among the public and the media as to whether Labour could ever return to government.

Kinnock then resigned as leader and was replaced by John Smith. Once again the battle erupted between the old guard on the party’s left and those identified as “modernisers”. The old guard argued that trends showed they were regaining strength under Smith’s strong leadership. Meanwhile, the breakaway SDP merged with the Liberal Party. The new Liberal Democrats seemed to pose a major threat to the Labour base. Tony Blair (the Shadow Home Secretary) had an entirely different vision. Blair, the leader of the “modernizing” faction (Blairites), argued that the long-term trends had to be reversed, arguing that the party was too locked into a base that was shrinking, since it was based on the working-class, on trade unions, and on residents of subsidized council housing. Blairites argued that the rapidly growing middle class was largely ignored, as well as more ambitious working-class families. It was said that they aspired to become middle-class, but accepted the Conservative argument that Labour was holding ambitious people back, with its leveling down policies.[clarification needed] They increasingly saw Labour in a negative light, regarding higher taxes and higher interest rates. In order to present a fresh face and new policies to the electorate, New Labour needed more than fresh leaders; it had to jettison outdated policies, argued the modernizers.[39] The first step was procedural, but essential. Calling on the slogan, “One Member, One Vote” Blair (with some help from Smith) defeated the union element and ended block voting by leaders of labour unions.[40] Blair and the modernizers called for radical adjustment of Party goals by repealing “Clause IV,” the historic commitment to nationalization of industry. This was achieved in 1995.[41]

The Black Wednesday economic disaster in September 1992 left the Conservative government’s reputation for monetary excellence in tatters, and by the end of that year Labour had a comfortable lead over the Tories in the opinion polls. Although the recession was declared over in April 1993 and a period of strong and sustained economic growth followed, coupled with a relatively swift fall in unemployment, the Labour lead in the opinion polls remained strong. However, Smith died from a heart attack in May 1994.[42]

“New Labour” government, 1997–2010

Tony Blair continued to move the party further to the centre, abandoning the largely symbolic Clause Four at the 1995 mini-conference in a strategy to increase the party’s appeal to “middle England“. More than a simple re-branding, however, the project would draw upon the Third Way strategy, informed by the thoughts of the British sociologist Anthony Giddens.

“New Labour” was first termed as an alternative branding for the Labour Party, dating from a conference slogan first used by the Labour Party in 1994, which was later seen in a draft manifesto published by the party in 1996, called New Labour, New Life For Britain. It was a continuation of the trend that had begun under the leadership of Neil Kinnock. “New Labour” as a name has no official status, but remains in common use to distinguish modernisers from those holding to more traditional positions, normally referred to as “Old Labour”.

New Labour is a party of ideas and ideals but not of outdated ideology. What counts is what works. The objectives are radical. The means will be modern.[43]

The Labour Party won the 1997 general election with a landslide majority of 179; it was the largest Labour majority ever, and the largest swing to a political party achieved since 1945. Over the next decade, a wide range of progressive social reforms were enacted,[44][45] with millions lifted out of poverty during Labour’s time in office largely as a result of various tax and benefit reforms.[46][47][48]

Among the early acts of Blair’s government were the establishment of the national minimum wage, the devolution of power to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, major changes to the regulation of the banking system, and the re-creation of a city-wide government body for London, the Greater London Authority, with its own elected-Mayor.

Combined with a Conservative opposition that had yet to organise effectively under William Hague, and the continuing popularity of Blair, Labour went on to win the 2001 election with a similar majority, dubbed the “quiet landslide” by the media.[49] In 2003 Labour introduced tax credits, government top-ups to the pay of low-wage workers.

A perceived turning point was when Blair controversially allied himself with US President George W. Bush in supporting theIraq War, which caused him to lose much of his political support.[50] The UN Secretary-General, among many, considered the war illegal and a violation of the UN Charter.[51][52] The Iraq War was deeply unpopular in most western countries, with Western governments divided in their support[53] and under pressure from worldwide popular protests. The decisions that led up to the Iraq war and its subsequent conduct are currently the subject of Sir John Chilcot‘s Iraq Inquiry.

In the 2005 general election, Labour was re-elected for a third term, but with a reduced majority of 66.